Art and War in the Renaissance:

The Battle of Pavia Tapestries

KIMBELL ART MUSEUM

from June 16 through September 15, 2024

Seven lavish tapestries depict the battle of Pavia,

commemorating Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s

decisive victory over French King Francis I

MONUMENTAL IN SCALE

Each tapestry measuring about twenty-eight feet wide and fourteen feet high—drawing viewers into the world of Renaissance history, military technology, and fashion.The scenes depict the key moments of the battle with soldiers and horses portrayed almost life-size.

THE THREE PROTAGONIST OF THIS EPIC

Carlos V, Holy Roman Emperor (left), Francis I, King of France (center)

and the town of Pavia in northern Italy (right)

The outcome was of major significance: many of the rank and file of the French army were killed, along with a significant number of noblemen. Most humiliating of all, Francis I was taken prisoner, leading to a year of captivity for him in Madrid. The resounding defeat of the French army at Pavia brought an end to long-standing French aspirations to conquer the northern Italian peninsula and changed the balance of power not only in that region but throughout the continent, marking a point of no return in European political and military history.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 7 TAPESTRIES

1 The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage Train into the Battlefield,

and the Surrender of the Swiss Pikemen of the French Army

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and

silver thread, 172 x 347 1/4 in. (437 x 882 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: Bernard van Orley created numerous picturesque details of the imperial camp followers—the civilians who traveled with the army, including family members, porters, cooks, merchants, engineers, surgeons, clergy, and others—many of whom hurry to claim the spoils of war upon the French troops’ imminent defeat. In the foreground, a churlish mercenary soldier accompanied by his son or a page catches our eye as he bounds forward with some chickens hanging from his pike—a common trope of plunder. Behind him, a friar and a few richly attired women enter the battlefield, while a chained monkey climbs above his cage, which has been loaded on the back of a horse. The weavers brilliantly capture the varied facial expressions of the motley entourage and vivid details like the multicolored chicken.

DETAIL At center foreground, an agitated group of soldiers represents the defeated French troops. To the left, a soldier rests his hand on the blade of an immense two-handed sword in the ground that served as a gathering spot for troops during the battle. Discarded weapons at their feet, a cowering drummer and fifer seem to sink under the weight of their heavy chains bedecked with fleurs-de-lis and a red rampant animal. A standard bearer next to them allows the French flag to fall to the ground, signaling the imminent defeat of the French forces. Nearby, soldiers wearing white crosses and imploring expressions doff their hats in humility and hold their right hands up in the air toward the imposing imperial horseman to indicate their submission.

DETAIL:The figure in light blue clothing wielding an immense pike that reaches from top to bottom of the tapestry is the valiant Swiss captain Johann von Diesbach, who offers up his life to an imperial knight whose sword is raised to deliver a fatal blow. By dying on the battlefield, Diesbach upholds his honor. The weavers have captured the splendor of the imperial horsemen in gleaming armor at right, identified by their red and white sashes and mounted on magnificent steeds.

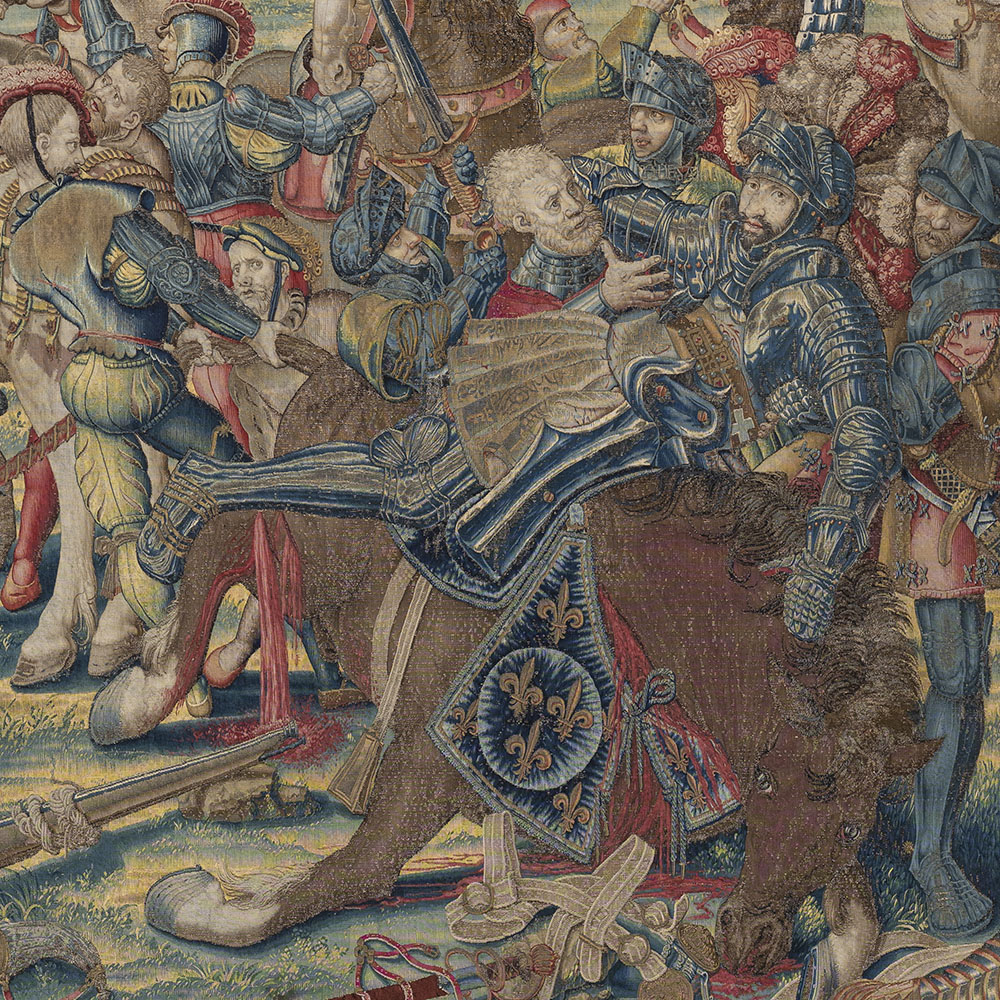

- 2 The Surrender of King Francis I

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

168 7/8 x 341 3/8 in. (429 x 867 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: This tapestry depicts the climactic event of the battle: the capture of the king of France by imperial troops. To the left, Francis I is helped from his dying horse—shot with a firearm—by imperial military officers. At far left, Charles de Lannoy, viceroy of Naples and commander of the imperial army, dismounts to accept the surrender of the king of France. The swords raised high by the noble horsemen in the center of the tapestry denote imperial victory. Francis was imprisoned in Italy and then taken to Spain. He was released upon signing the 1526 Treaty of Madrid that abandoned French claim to the Duchies of Milan and Burgundy and other important territories—terms he broke shortly thereafter. Although hostilities resumed, Habsburg ascendency in Europe and beyond was determined at the Battle of Pavia.

DETAIL: The central bearded figure, who has been variously identified, is probably another depiction of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, who was present at Francis I’s capture. The raised swords denote victory and are mentioned in contemporary accounts, as is Bourbon’s honorable and deferential treatment of Francis I. Following the Battle of Pavia, in 1527 Bourbon accompanied the imperial troops south to Rome to relay Charles V’s warning to the pope to come to his terms. Bourbon was famously killed outside the city walls, and the mutinous imperial troops proceeded to sack Rome. His portrait in the tapestry would honor his service to Emperor Charles V.

DETAIL

The battlefield is located on the outskirts of the besieged city of Pavia in northern Italy. The visitor will be amazed by the pictorial quality and realism of the characters depicted in these tapestries, which were first presented at the court of Charles V in 1531.

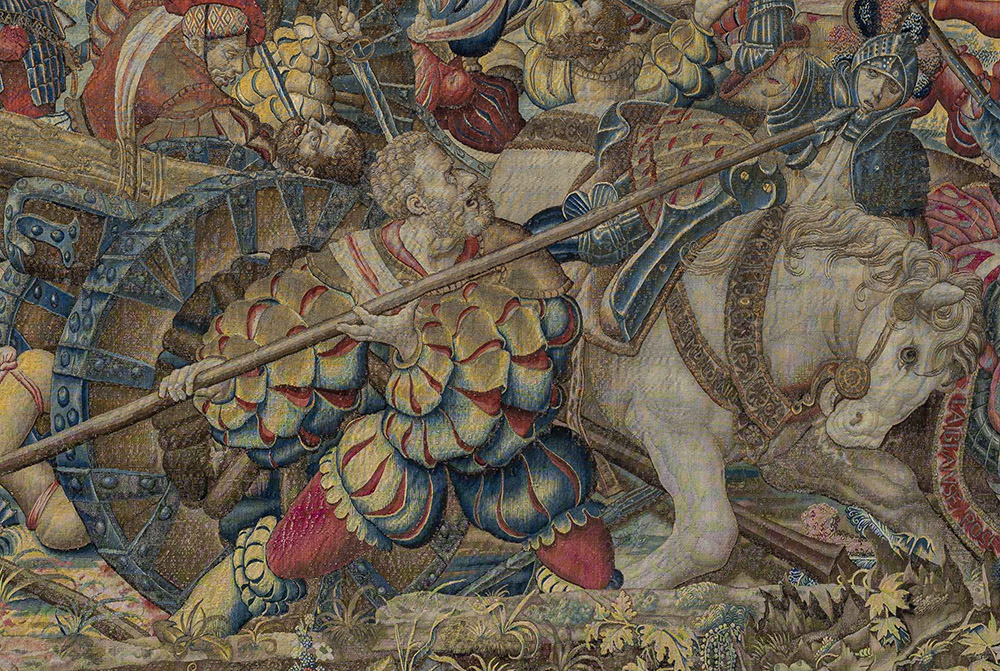

- 3 The Advance of the Imperial Army and Counterattack

of the French Cavalry Led by King Francis I

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

163 3/8 x 345 5/8 in. (415 x 878 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: An early stage of the battle is depicted in this tapestry. The scene takes place in the park surrounding Mirabello Castle, a large, walled hunting estate located just outside Pavia, where the French encamped during the months-long siege. During the night, the imperial troops breached the park’s brick walls and infiltrated their enemy’s position by hiding in the woods. Now, at dawn, they advance toward the French army, drawing them into a trap. In response, the French launch a massive charge of heavy cavalry led by King Francis I himself.

DETAIL: On the right side of the tapestry, in the middle ground, Francis I is depicted at an earlier moment, leading the French cavalry charge. The king—recognizable by the ornate plumage of his helmet, his luxurious armor and clothing, and the fleurs-de-lis that adorn his steed, is followed by his knights. With his sword held high, he prepares to kill his Neapolitan opponent, the Marquis of Civita Sant’Angelo, whose broken lance touches the ground.

DETAIL: In the lower right corner are imperial soldiers from the Spanish advance guard, identifiable by the red saltire (X-shaped) crosses on the white shirts pulled over their doublets, which allow them to be seen in darkness and not mistaken for the enemy by their allies. They aim their arquebuses toward the French cavalry, often targeting the horses and slaughtering large numbers of the enemy. The arquebusiers’ activity is described in detail. The bandoliers slung across their torsos hold cartridges of ammunition. On their waists they carry powder horns and pouches with lead shot. The guns were ignited with a matchlock mechanism: a smoldering cord match held to the flash pan kindled the priming powder, which in turn ignited the propellant in the gun barrel. The arquebusiers moved to the rear to reload their guns, as others advanced to take aim.

- 4 The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry,

Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery

by the Lansquenets under Georg von Frundsberg

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c.1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

176 3/4 x 340 1/8 in. (449 x 864 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: The chaos and violence of the battlefield in the fog of dawn is captured in this tapestry as imperial arquebusiers under command of the Marquis of Pescara, Fernando (Ferrante) Francesco d’Avalos, decimate the French cavalry. At the right, Germanic mercenary soldiers called landsknechts, also known as lansquenets, led by Georg von Frundsberg, are recognizable by the white-and-red bands they wear over one shoulder.

DETAIL: The landsknechts attack the artillery positions held by renegade mercenaries known as Black Bands, who have been paid to fight for the king of France. These bitter enemies fight to the death, with the imperial infantry prevailing. In the background, the endless rows of upturned pikes evoke the imposing scale of the battle. Another key imperial leader is depicted toward the right side of the tapestry, standing beside a cannon decorated with fleurs-de-lis: Georg von Frundsberg, formidable commander of the German lansquenets. Holding an upright halberd, he wears half-armor and the imperial white and red sash, with his name picked out in gold letters on his sword’s belt. Frundsberg triumphantly signals the capture of the French artillery.

DETAIL

During the Renaissance, monarchs and religious leaders glorified their power and wealth through the art of tapestry, commissioning some of Europe’s greatest artists to commemorate significant events through the lavish medium. Elaborate tapestries, much more costly than paintings, could serve as tools for dynamic storytelling and political propaganda, depicting histories in fine wool, silk, and metal-wrapped thread at monumental scale.

5 The Invasion of the French Camp and the Flight

of the Ladies and Servants

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

171 5/8 x 322 in. (436 x 818 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: In this tapestry, the imperial forces storm in from the left to capture the French headquarters, overwhelming all resistance. In the left foreground, a burly imperial foot soldier, or landsknecht, wields a hefty double-handed sword to break the pike of his opponent. Such elite, experienced soldiers—armed with huge double-bladed swords or with halberds (polearms topped with an axe blade and often hooks used to unmount horsemen) or with the long firearms called arquebuses—were known as “doppelsoldner,” since they received double pay. The landsknechts paid for their clothing and armor—here an impressive set of half-armor with chainmail protecting the chest. Above this group of infantry, imperial cavalry and Germanic pikemen attack the besieged French troops, and a French horseman, identifiable by his white cross, is killed with a lance.

DETAIL: The French are deployed in two trenches, protected by their artillery positioned between wicker-clad emplacements called gabions. Within the encampment, the excitement of the battle is underscored by explosions that drive mules and soldiers in various directions. Critically for the outcome of the battle, none of the French cannons are firing. Although the French had an advantage in numbers of large guns, ammunition supply and flawed strategy prevented them from using the artillery, which would have struck their own troops. At the end of the battle, the French artillery was a significant part of the war booty obtained by the imperial troops.

DETAIL: In the foreground, the French baggage train—civilians in the French army’s retinue—begins to flee both to the right and left. Family members of the combatants, vendors, porters, cooks, orderlies, and others attended to the army’s daily operations. Led by a bounding hound, a young woman—purse and keys hanging from her waist—escapes with a fluffy dog. An elegant lady—perhaps a French officer’s wife or a courtesan—in a red velvet robe rides sidesaddle on a white mule with a lavish harness.

- 6 The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial Troops from Pavia,

and the Rout of the Swiss Guard

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

165 3/8 x 350 in. (420 x 889 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: At the lower left corner of the tapestry, two soldiers in extravagantly plumed hats, possibly officers, will doubtless join their compatriots scrambling over the brick wall to escape the Spanish imperial onslaught. One wields a double-handed sword marked with a white cross over his shoulder, and the other, in half-armor, bears the French flag. Most infantry were pikemen, but the most skilled, experienced soldiers (“doppelsoldner”) wielded huge double-handed swords or halberds (polearms topped with an axe blade), which they used to penetrate the enemy’s pike formation, or carried arquebuses.

DETAIL: Visconti Castle, the garrison commanded by the Spanish captain Antonio de Leyva, whose soldiers had resisted the French siege for four months, is shown in the upper left of the tapestry. De Leyva’s troops make a sortie from the city and strike what remains of the enemy. Bearing the brunt of the Spanish sortie was a Swiss infantry unit that was quickly routed.

In the middle ground of the tapestry, French soldiers and civilians can be seen emerging from some of the protective dugouts in an effort to quickly escape from these now unsafe positions. Nearby are two French horsemen, one of whom is identified with an embroidered inscription on his horse’s bridle, reading “Mofort,” as François de Laval, Count of Montfort, who is listed among the dead at Pavia.

DETAIL

The Artists. The seven Battle of Pavia tapestries are some of the most awe-inspiring examples of this oftenoverlooked yet highly prized Renaissance artform. They required remarkable feats of collaboration between artists and weavers—a single panel could take more than a year to produce. Designed by court artist Bernard van Orley (c. 1488–1541), the tapestries were woven in Brussels by Willem and Jan Dermoyen (both active 1520s–1540s) in deeply saturated hues and exquisite detail, luxuriously highlighted with gold and silver thread.

7 The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon

Willem and Jan Dermoyen, after Bernard van Orley, c. 1528–31. Wool, silk, gold, and silver thread,

172 3/8 x 308 1/4 in. (438 x 783 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL: Another key event of the battle unfolds in this tapestry. At left and center, battlefield skirmishes show the formerly invincible heavy French cavalry, weighed down by head-to-toe armor, routed by the nimbler Spanish cavalry wearing half-armor on smaller, more agile horses. Overwhelmed by the unstoppable Spanish breakthrough, Charles IV, Duke of Alençon, brother-in-law of Francis I and commander of the French rear guard, leaves his position and, instead of engaging in combat, retreats to the other side of the Ticino River, shown at far right. In France, his actions will lead to accusations of cowardice and treachery, although his tactics ensured the survival of his troops.

DETAIL: At lower left, a soldier desperately clings to a branch to save himself from drowning, as feathered berets and discarded weapons float in the rushing waters that have already claimed many victims. Elements such as the way the soldier’s body is seen beneath the rippling water showcase the masterful skill of the weavers in replicating painterly detail and illusionistic effects. Their sophisticated and varied weaving techniques required using a high warp count and ever-finer shades of dyed silk and wool to capture subtle color variations, as in the veins of the soldier’s hand.

DETAIL: The bucolic landscape with fields of grazing cattle and gentle wooded hills in the upper part of the tapestry—more Flemish or Northern than Italian in inspiration—suggests a world of peace and safety remote from the horrors of war shown in the battlefield, where soldiers fight to the death.

ALONGSIDE THE TAPESTRIES

Impressive examples of precious arms and armor from the period

evoke the human experience of war in the Renaissance

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with thrusting sword

ca. 1550. Steel, wood, leather, and cloth, 57 1/8 x 82 5/8 x 35 3/8 in. (145

x 210 x 90 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL OF Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with thrusting sword

“Medallion” armor garniture (detail)

ca. 1575. Steel, 67 3/4 in. (172 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Pompeo della Cesa (Italian, active ca. 1537–1610),”Volat” armor garniture

1590. Steel, 67 3/4 in.(172 cm), pike 49 1/4 in. (125 cm).

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Attributed to Pietro Paolo Malfettano (Italian, active 16th century),

Ceremonial helmet originally from Canicattì, ca. 1570.

Burnished steel, silver foil, and wood, 12 1/4 x 13 x 7 7/8 in. (31 x 33 x 20 cm).

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL OF Ceremonial helmet originally from Canicattì

Rotella shield, ca. 1590.

Burnished steel, silver foil, and wood, Diam. 23 1/4 in. (59 cm) x D. 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm)

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

DETAIL OF Rotella shield

Giovan Battista Visconti (Italian, active 16th century)

Ranuccio Farnese wheel-lock gun, 1596

Forged steel and wood, 52 3/8 x 9 1/2 x 3 1/8 in. (133 x 24 x 8 cm)

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Agate dagger, early 16th century. Sardonyx agate

shagreen, and steel, L. 16 1/8 in. (41 cm). Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Attributed to Francesco Francia (Italian, ca. 1450–1517)

Triumph of Abundance (fragment of horse harness), early 16th century

Boiled, painted, and gilded leather, 29 1/2 x 16 7/8 in. (75 x 43 cm).

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

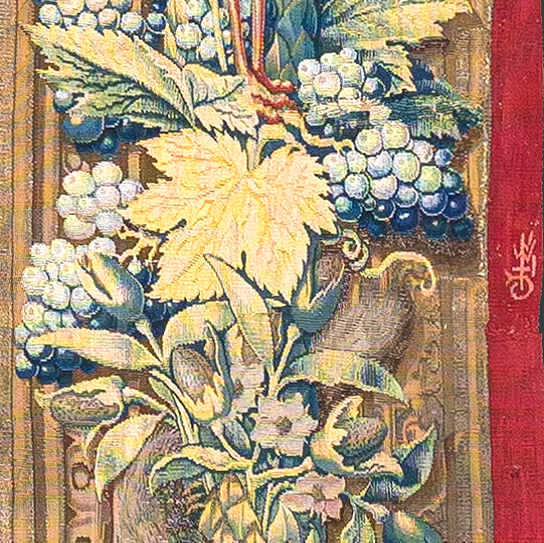

Willem and Jan Dermoyen’s weavers’ mark

STATEMENTS

Eric Lee, Kimbell Art Museum director sed “The Battle of Pavia tapestries are at once dazzlingly intricate works of fine art, powerful historical documents, and awe-inspiring visual narratives that will envelop visitors in early sixteenth-century art and history,”

Eric Lee, Kimbell Art Museum director sed “The Battle of Pavia tapestries are at once dazzlingly intricate works of fine art, powerful historical documents, and awe-inspiring visual narratives that will envelop visitors in early sixteenth-century art and history,”

George TM Shackelford sed “The lucky members of the emperor’s court were surrounded by a massive, colorful panorama of a critical battle between two rivals—Francis I and Charles V—that had changed modern history.

George TM Shackelford sed “The lucky members of the emperor’s court were surrounded by a massive, colorful panorama of a critical battle between two rivals—Francis I and Charles V—that had changed modern history.

The exhibition is organized by the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte and The Museum Box in collaboration with the Kimbell Art Museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

SUPPORT. Promotional support for the Kimbell Art Museum and its exhibitions is provided by American Airlines, PaperCity, and NBC 5. Additional support is provided by Arts Fort Worth and the Texas Commission on the Arts.

KIMBELL ART MUSEUM

3333 Camp Bowie Boulevard, Fort Worth, Texas 76107

817-332-8451 kimbellart.org