A Passion for Jade: The Bishop Collection

July 2, 2022–February 17, 2025

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Jade, the most esteemed stone in China, and many other hard stones,

are on display in this exhibition that brings together more than a hundred

remarkable objects from the Heber Bishop Collection.

Refined works represent the sophisticated artistry of Chinese gemstone

cutters during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

Pillow in the shape of an infant boy

Pillow in the shape of an infant boy. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century.

Jade (jadeite). H. 4 3/4 in. (12.1 cm); W. 4 in. (10.2 cm); L. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.426)

Jadeite became a favored material at the eighteenth-century Qing court for its intense green color, high translucency, and vitreous luster. This remarkable sculpture of a crouching boy is modeled after the ceramic pillows of the same shape that were produced at the famed kilns of the Song period (960–1279). It not only illustrates the elegant taste of the Qing court but also denotes the increased access to the prized material. The boy, a common motif in Chinese art, expresses the wish for multiple children to carry on the family line.

Immortal

Immortal.China, Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95), 18th century. Jade (nephrite)

Immortal.China, Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95), 18th century. Jade (nephrite)

H.11 15/16 in. (30.4 cm); W. 6 1/8 in. (15.5 cm); D. 4 3/4 in. (12 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.411)

Belonging to a pair of figures depicts two young attendants holding large serving bowls. Their unusually large earlobes, quiet expressions with subtle smiles, and long robes with broad sleeves all suggest that they are from the land of the immortals. The substantial size and refined craftsmanship of these sculptures are hallmarks of the imperial workshop, which boasted an ample supply of precious jade material and the most talented carving masters.

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite).

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite).

H. 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm); W. 6 3/4 in. (17.2 cm); D. 2 11/16 in. (6.8 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.640)

A luohan, (arhat, in Sanskrit) is a Buddhist sage who has achieved enlightenment. Groups of sixteen, eighteen, and five-hundred luohans were worshipped in China, where they were a common theme in painting and the decorative arts. The beautifully engraved inscription on this sculpture identifies the luohan as Kanaka, the eighth in the set of sixteen, and explains that the Qianlong emperor had this sculpture made as part of a set of sixteen images for a shrine in the palace.

Vase in the shape of a heavenly rooster

Vase in the shape of a heavenly rooster. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite).

Vase in the shape of a heavenly rooster. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite).

H. 5 5/16 in. (13.5 cm); W. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm); D. 2 11/16 in. (6.9 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.658a, b)

Containers in the shape of a rooster carrying a vessel on its back are an invention of Song dynasty (960–1279) antiquarians, who believed that such ritual vessels existed in the classical age of ancient China. This jade vessel was modeled after the bronze ones that were catalogued as “heavenly rooster vases” (tianjizun) in the collection of Emperor Qianlong (r. 1736–95), who had a deep interest in the antiquities. The term “heavenly rooster” comes from a Chinese legend about a mythical bird whose crowing awakens the whole world.

Horse carrying books

Horse carrying books. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century. Jade (nephrite)

Horse carrying books. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century. Jade (nephrite)

with semiprecious stone inlays. H. 4 9/16 in. (11.6 cm); W. 4 1/8 in. (10.4 cm); D. 2 1/16 in. (5.3 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.739)

This sculpture is typical of an innovative style of the eighteenth to early nineteenth century, when Chinese craftspeople created novel designs by combining traditional forms with decorative elements from other cultures. While the compact and broad shapes of the animals are derived from the native tradition, the sparkling inlays of semiprecious stones are unmistakably inspired by the jades of Mughal India.

Elephant carrying a vase

Elephant carrying a vase. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century. Jade (nephrite)

Elephant carrying a vase. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century. Jade (nephrite)

with semiprecious stone inlays. H. 4 9/16 in. (11.6 cm); W. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm); D. 2 in. (5.1 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.740

This sculpture is typical of an innovative style of the eighteenth to early nineteenth century, when Chinese craftspeople created novel designs by combining traditional forms with decorative elements from other cultures. While the compact and broad shapes of the animals are derived from the native tradition, the sparkling inlays of semiprecious stones are unmistakably inspired by the jades of Mughal India.

Basin

Basin. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95), dated 1774. Jade (nephrite)

Basin. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95), dated 1774. Jade (nephrite)

H. 7 5/8 in. (19.3 cm); W. 29 15/16 in. (76. 1 cm); D. 16 15/16 in. (43 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.689

On the walls of this large basin, five spirited dragons—their sinuous bodies carved in high relief—chase two flaming pearls in and out of swirling clouds. A poem by Emperor Qianlong inscribed on the interior floor dates the jade to 1774 and points to Khotan in far northwestern China as the source of this huge boulder. The overall shape and decoration suggest that the basin was inspired by the colossal jade wine container that Khubilai Khan (1215–1294) commissioned in 1265.

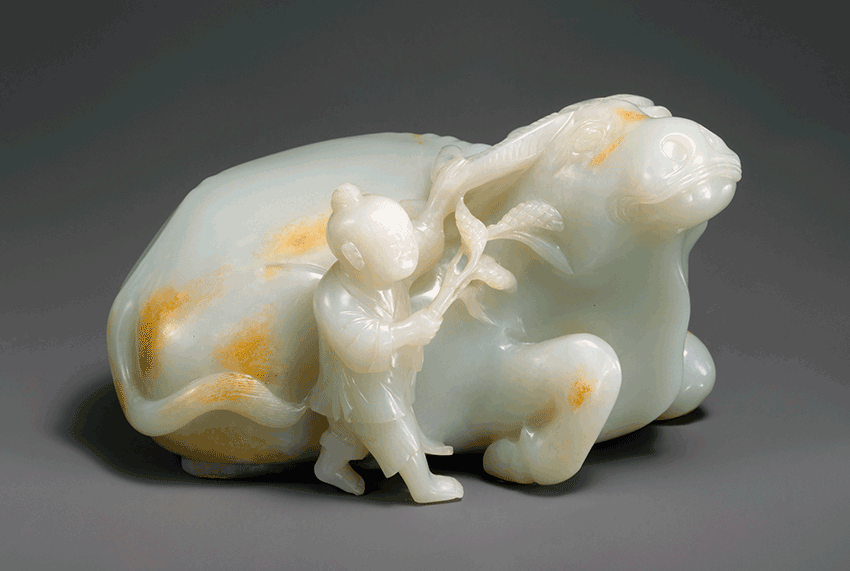

Boy with water buffalo

Boy with water buffalo. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite)

H. 5 3/16 in. (13.2 cm); W. 4 3/16 in. (10.6 cm); L. 7 5/16 in. (18.5 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.438)

Auspicious symbols and visual puns expressing good wishes are recurring themes in Chinese decorative art. A delightful example is this white nephrite sculpture that depicts a small boy gently prodding his companion, a large water buffalo, with a stalk of rice. The ears of rice symbolize a good harvest and rhyme with the Chinese word for “year” (sui), thus implying the wish for “a good harvest year after year” (sui sui nian feng).

Water vessel in the shape of a marriage cup

Water vessel in the shape of a marriage cup. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century.

Water vessel in the shape of a marriage cup. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century.

Jade (nephrite) H. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm); W. 8 in. (20.3 cm); L. 5 9/16 in. (14.2 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.367)

The marriage cup, which derives its name from the shape of two joined rhombuses, signifies the ideal union of two individuals. On one side of the cup are two small boys, one holding a ruyi scepter and the other wearing a vest decorated with coin shapes. Their companions on the other side hold a peach and a vase filled with coral. While the accessories in their hands stand for happiness, wealth, and longevity, the boys themselves allude to the proliferation of offspring as the hopeful result of a marriage.

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century.

Seated luohan (arhat) in a grotto. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th–19th century.

Lapis lazuli. H. 7 1/8 in. (18.1 cm); W. 10 in. (25.4 cm).

he Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.917)

This superb sculpture of lapis lazuli depicts a Buddhist sage meditating in a rocky cave under a craggy tree. The master carver demonstrated his formidable skill by managing to turn the large light gray blotches of the stone into the gnarled tree trunk and the whitish spots into the highlights on the monk’s face.

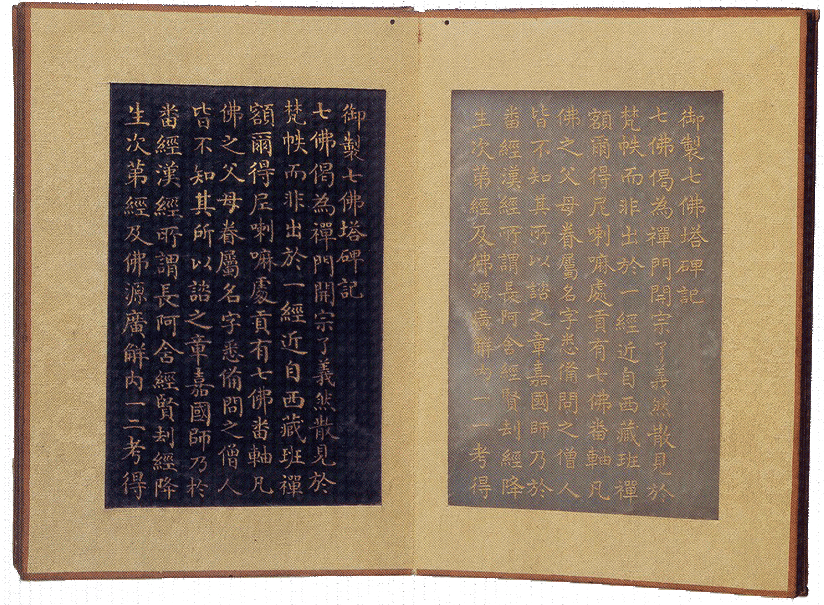

Jade book

Jade book. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite)

Jade book. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century. Jade (nephrite)

H. 5 9/16 in. (14.1 cm); W. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm); L. 1 9/16 in. (4 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902 (02.18.527)

This jade book is composed of pale green jade tablets engraved with an essay by the Qianlong emperor commemorating the completion of the Seven Buddhas Pagoda in the imperial garden. The text is carved in regular script calligraphy and filled with gold. Paired with the tablets are black paper pages, which bear the same text written in gold ink. This superb work not only exemplifies Emperor Qianlong’s particular fondness for jade and taste for lavish display but also reveals the Qing court’s partiality to Tibetan Buddhism over other contemporary religions.

Archaic-style vase with dragons

Archaic-style vase with dragons, China,18th–19th century,Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

This vessel takes the form of an ancient bronze ritual wine container (fanggu). The dragons, a contemporary addition, enliven the classical model with a new sensibility. The Qing-dynasty vessel would not have been used for wine, like its ancient inspiration, but was a decorative object designed to display the owner’s learned taste.

Double vessel with mythical beasts (champion vase)

Double vessel with mythical beasts (champion vase) China,18th–19th century, Jade.

Double vessel with mythical beasts (champion vase) China,18th–19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, , Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

The term “champion vase,” which appears only in Western scholarship, refers to vessels that have two narrow vertical compartments connected by a carved mythical bird. It may be a loose translation of yingxiong bei, or hero’s cup, referring to the eagle (ying) and the bear (xiong) upon which such vessels stand. Based on an archaic bronze vessel type that can be traced back to the second century B.C., champion vases were revived beginning in the sixteenth century and were manufactured in the following centuries in different media, including jade, cloisonné enamel, and rhinoceros horn.

Boulder with Daoist paradise

Boulder with Daoist paradise, China, 18th century, Jade.

Boulder with Daoist paradise, China, 18th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

This impressive jade sculpture represents a Daoist paradise where immortals, cranes, and deer move through a mountainous landscape punctuated by pines, a waterfall, and a pavilion that stands beside a peach tree laden with fruit. Lower down the slope, a servant offers a platter of these “peaches of immortality” to two bearded figures. The otherworldly atmosphere is further enhanced by the meandering clouds that encircle the crest of the mountain. Jade, which is sonorous when struck but is harder than steel, has long been associated with moral virtue and immortality. The theme of reclusion within misty, fantastic realms appears in youxian (Wandering in Transcendence) poetry of the Six Dynasties period (220–589), and was a very popular painting subject beginning in the Tang dynasty (618–906).

Brush holder with gathering at the Orchid Pavilion

Brush holder with gathering at the Orchid Pavilion, China, 18th–19th century, Jade.

Brush holder with gathering at the Orchid Pavilion, China, 18th–19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

The intricate carving on the curving walls of this brush holder depicts a lively scene of the legendary Orchid Pavilion Gathering, in which master calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303–361) and his friends sit amid trees and rocks, composing poems and drinking wine from cups floated down a stream. This extraordinary work is among the first pieces in the collection that kindled Bishop’s passion for jade, leading to the creation of his renowned collection.

Table screen with landscape scene

Table screen with landscape scene, China,18th–19th century, Jade.

Table screen with landscape scene, China,18th–19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

Bell

Bell, China,18th–19th century, Jade.

Bell, China,18th–19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

Garment hook in the shape of a phoenix

Garment hook in the shape of a phoenix, China,19th century, Jade.

Garment hook in the shape of a phoenix, China,19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

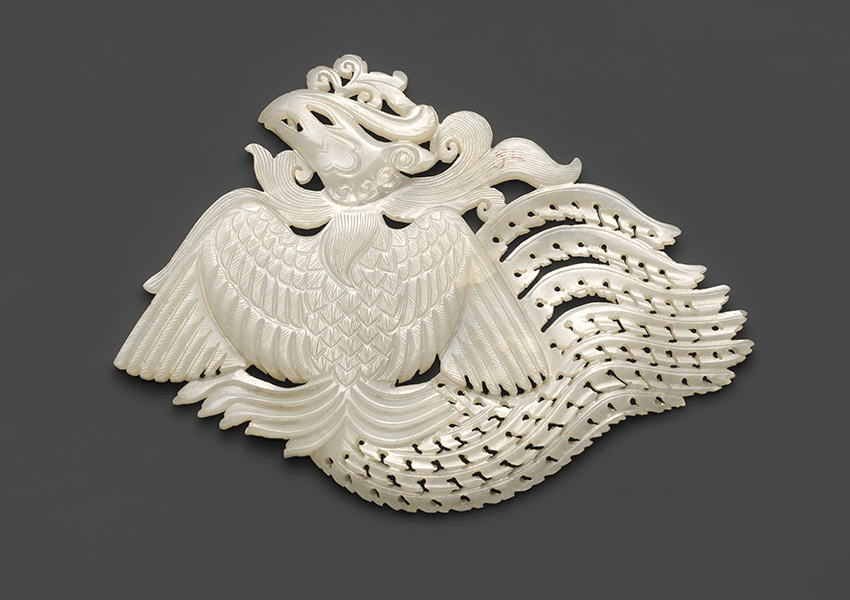

Fitting in the shape of a phoenix

Fitting in the shape of a phoenix, China,18th century.

Fitting in the shape of a phoenix, China,18th century.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

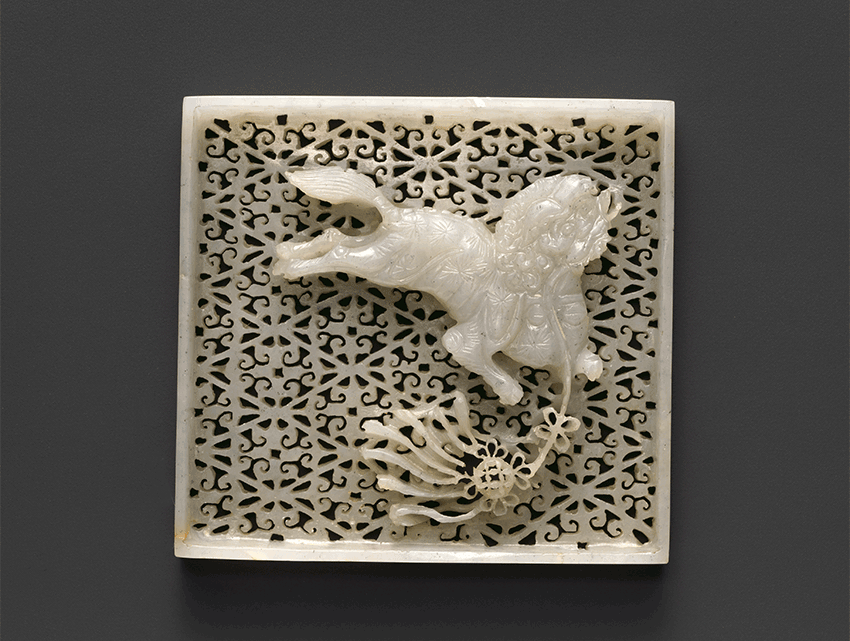

Belt plaque

Belt plaque, China,16th century, Jade.

Belt plaque, China,16th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

Belt plaque

Belt plaque, China,16th–17th century, Jade.

Belt plaque, China,16th–17th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

Ornament

Ornament, China, 18th–19th century, Jade.

Ornament, China, 18th–19th century, Jade.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902

The exhibition is made possible by

the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Exhibitions

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

https://www.metmuseum.org/

The Met Fifth Avenue, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028, Phone: 212-535-7710

The Met Cloisters, 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tryon Park,

New York, NY 10040 Phone: 212-923-3700