AFRICAN ART

Permanent Collection

HIGH MUSEUM OF ART. Atlanta

Chokwe Artist, Angola, Mask

With a curatorial department devoted solely to African art since 2001,

and a curatorial position endowed by Fred and Rita Richman,

the High’s collection has grown to encompass the dynamic diversity

of African art forms from ancient to contemporary.

The heart of the collection includes sculptures from west and central Africa created between 1850 and 1950, including a Baga sculpture from Guinea gifted in 1953 by Helena Rubenstein. Other significant gifts include more than 450 works from Fred and Rita Richman that form the core of the African collection.

Major gifts from Dr. Bernard and Patricia Wagner starting in 2005 spotlight Yoruba art, including masks, figurative sculpture, beadwork, metalwork and ceramic arts.

Collection Highlights

NIGERIA

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Dance Staff for Esu/Elegba”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

16 x 3 1/2 x 8 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

1980.500.72

In this dance staff made to honor Èshù, two faces look in opposite directions.

Èshù is a deity honored by the Yoruba people of Nigeria and known throughout the African Diaspora as Elegua or Elegba.

Èshù mediates opposing forces to bring together different worlds. He bears messages from the ancestral and spiritual realms, opens doors, and guards crossroads.

Shrines to Èshù are placed wherever there is potential for conflict. Though known as a mischief-maker and agent provocateur, Èshù ultimately works to promote order and harmony in the universe.

Èshù teaches wisdom, reminding people to look at the world from more than one point of view.

Yoruba Artist

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Kneeling Figure with Bowl”

Nineteenth century

Wood

9 3/4 x 3 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Gift of Bernard and Patricia Wagner

2007.275

The kneeling gift bearer is common on many altars

because of its capacity to serve as a surrogate for the

owner of an altar or the person who commissioned it.

This example is unusual for its elongated form. Its kneeling pose communicates respect, courtesy, and supplication.

When placed on an altar that represents the “outer head” of a Yoruba deity, the receptacles of kneeling figures such as

this one are used to conceal natural objects signifying

the “inner head” of a that deity.

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Pair of Twin Figures” (ère ìbejì)

nineteenth century

Wood, pigment, beads, and cowrie shells

13 3/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.287.1-2

Twins are more common in Yoruba communities than anywhere else in the world. Ère ìbejì figures such as these represent deceased twin children. When a twin dies, a figure is carved to localize the spirit of the deceased. If neglected, its spirit might feel abandoned and invite the soul of the surviving twin to join it in the beyond. The smooth, worn surfaces of these figures show that they have been cared for devotedly. Their elaborate ceremonial coiffures are rubbed with a powdered dye called Rickett’s blueing, which was used by the British to whiten laundry during the colonial era. Yoruba artists used the powder as a substitute for indigo.

Yoruba Artist

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Dance Staff for Sango”

early–mid twentieth century

Wood and pigment

20 1/2 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.107

Followers of Shango—the Yoruba thunder god and the deity associated with divine justice—carry dance staffs on ceremonial occasions.

The kneeling female figure depicted on this dance staff represents a priestess or devotee of Shango.

Shango is symbolized by the double-axe-blade motif, which refers to thunderstorms (Neolithic axe-heads are described as having being thrown down from the sky by the thunder deity).

Yoruba Artist, Abeokuta,

Nigeria

“Blacksmith’s Staff” (Opa Ogun)

Nineteenth century

Bronze

20 1/2 x 5 1/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

1980.500.74

Designed for ceremonial use, this staff (òpá Ògún) distinguishes an individual as a senior blacksmith and possibly a renowned hunter and warrior who has been honored by the king with a chieftaincy title.

The bird motifs and projections on the figure’s headgear signify an ability to wield enormous physical and metaphysical powers due to close association with Ògún, the Yoruba god of iron.

Yoruba Artist

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Fan for Osun”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Brass

14 x 8 3/4 x 1 1/4 inches

Gift of Bernard and Patricia Wagner

2008.287

This elegant brass fan was created to honor Osun, the Yoruba goddess of beauty and fertility. Priestesses of Osun carry brass fans in processions along the banks of the Osun River during annual festivals dedicated to the deity.Osun relieves human anxiety in the same way that a fan cools the body. According to Yoruba oral tradition, Osun was excluded from the all-male council of gods. Consequently, their sacrifices were rejected at the door to paradise until Osun gave birth to Èshù, who served as mediator between this world and beyond, allowing order and prosperity to reign.

Yoruba Artist, OyoNigeria

Yoruba Artist, OyoNigeria

“Egungun Masquerade Costume”

Eighteenth–twentieth century (Exterior velvet panels: 1750–1850)

Cloth, cowrie shells, and wood

86 x 50 inches

Purchase through prior acquisitions

2002.2

In Yoruba communities ancestors are described as “beings from beyond,” aptly personified by otherworldly Egúngún masks such as this one.

These masks are worn at annual street festivals held in honor of the ancestors of a city’s founding lineages. This masquerade’s outer layers are made from imported velvets and factory manufactured cloth, while the inner layers are made of local handspun, hand-woven, indigo dyed cotton cloth.

An abundance of cowrie shells adorn the front of the mask and cascade in multiple strands both above and below. It is capped by a carved wooden bird’s head, which projects from a circular platform densely embedded with additional shells.

Edo Artist, Kingdom of Benin

Edo Artist, Kingdom of Benin

Nigeria

” Bracelet”

nineteenth century or earlier

Ivory

4 3/4 × 3 × 3 1/8 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.288

This ivory bracelet from the 800-year-old Edo Kingdom of Benin is decorated with motifs that refer to the great sixteenth-century warrior king Oba Esigie.

Motifs associated with Esigie were popular during the reign of the late-nineteenth-century king Oba Ovoranmwen.

The motifs include a Portuguese soldier on horseback and an image of the king himself, depicted in the guise of a leopard. The bracelet’s deep burgundy color is the result of repeated applications of red palm oil mixed with spirits.

Yoruba Artist

Yoruba Artist

Nigeria

“Crown of Obatala” (Ade Obatala)

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Glass beads, cloth, fiber, and leather

17 x 9 1/2 inches

Gift of Bernard and Patricia Wagner in memory of Erintunde Orisayomi Ogunseye Thurmon

2006.230

A Yoruba king (oba) is identified in public by a conical, beaded crown (adé) with a veil that transforms him into a living embodiment of Odùduwà, regarded as the first king of the Yoruba people. The bird at the top of the crown recalls the Yoruba creation narrative, which describes how Odùduwà used a bird to create the first land in Ilè Ifè at the beginning of time. The bird identifies the king as a descendant of Odùduwà and emphasizes his role as an intermediary between his subjects and the òrìsà, or gods, in the same way that a bird mediates between heaven and earth.

El Anatsui, one of Africa’s most compelling contemporary artists, produces works that are aesthetically and conceptually resonant with ancient African forms. In 1999 the Nigerian-based artist began a series of works he termed “metal cloth” sculptures. He joins bits of aluminum from the necks and tops of discarded local liquor bottles to form a glittering textile that recalls the 1,000-year-old tradition of strip-woven cloth made by men in West Africa.

Anatsui describes how he likes “to work with objects that have had a lot of human use because a certain charge is imbued, or loaded into the object.” Though he has participated in residencies worldwide and his art has been exhibited in Brazil, Denmark, France, Germany, Ghana, Italy, Japan, Nigeria, Spain, the United States, Wales, and beyond, Anatsui has chosen to stay in Africa, working in a large studio with many workshop assistants.

Democratic Republic of the CONGO

Metoko Artist

Metoko Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Male and Female Figures”

Nineteenth century

Wood. 16.25 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.308.1-2

In Metoko societies, paired male and female figures representing husband and wife were used in initiation rites to confer the status of kasimbi, one of the highest ranks within the association called Bukota, whose membership included both men and women. The paired figures provided behavioral models, encouraged healing, and promoted peace. The Richmans have made couples—an important subject in African art—a special theme in their collecting. These sculptures represent idealized images of men and women who bear the potential to give birth to future generations. Without children, one does not become an ancestor.

Luba Artist

Luba Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Adze”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood, copper, and iron

14 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.311

In Luba culture, to make or hold an adze signifies royalty and power. This symbolism is derived from oral histories that describe how a mythological hero established kingship by introducing advanced metal-working, forever connecting the two.

As a result, Luba blacksmiths are highly regarded, as in many African cultures. They are respected for their secret knowledge and expert metal-working skills, derived from the founding hero himself.

The tools and products of blacksmiths play significant roles in investiture rituals for Luba kings as well as in many other ceremonies and events.

Bembe Artist, Democratic

Bembe Artist, Democratic

Republic of the Congo

“Helmet Mask”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood and pigments

16 x 11 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Richman to mark the retirement of Gudmund Vigtel

1991.297

Masks like this performed during initiation rituals of the alunga association, a powerful men’s organization charged with educating teenage boys and maintaining law and order. As the young men learned the mysteries of the mask through songs, the mask instructed them, “alunga is not a man, but a thing, something from the bush, something from very remote times, something very awe-inspiring. Never profane its mysteries.” This mask has two pairs of eyes, each painted white to indicate spiritual insight. Alunga associations were banned by the Belgian government in 1947 because their authority represented a challenge to colonial rule.

Lwalwa Artist

Lwalwa Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Mask”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

11 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2004.150

Among the Lwalwa people of the southern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and neighboring Angola, initiation masks like this one are carved by politically powerful men who are also in charge of staging masquerade performances. Lwalwa masks present an ingenious distillation of forms.

They typically have concave faces bisected by long vertical noses, narrow slits for eyes, round ears, and rectangular mouths. White clay highlights fill the eyes, mouth, and ears.

Kongo Artist

Kongo Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Cross”

Mid seventeenth–mid eighteenth century

Bronze

7 3/4 × 4 3/4 × 5/8 inches

Gift in memory of Lew C. Deadmore

2005.319

At the end of the fifteenth century, Christianity was introduced to the Kingdom of the Kongo, along the coast of central Africa.

This influenced religious and artistic practices. Kongo artists created crosses and other objects of worship, combining their Kongolese and Christian iconography.

Here, Christ’s face is given African features. Crosses were not only used in Christian liturgy but also served additional diverse functions, in healing, in divination, as symbols of social status and political authority, and as hunting charms.

Kongo Artist

Kongo Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Royal Hat” (Mpu)

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Woven fiber 3 7/8 inches

Gift of Mrs. Pauline Lathrop Shomler

1982.277

Made of knotted raffia or pineapple-leaf fiber, hats such as this one were worn by political leaders throughout the region of the former Kingdom of the Kongo (founded ca. 1400), which flourished along the coastal region of central Africa. The finely detailed geometric patterns of this hat resemble those woven into the beautiful velvet-like raffia textiles worn by Kongo royalty and formerly used as currency throughout the kingdom. The geometric patterns of Kongo hats, textiles, and mats were associated with the maze-like layout of the royal palace and streets of the capital.

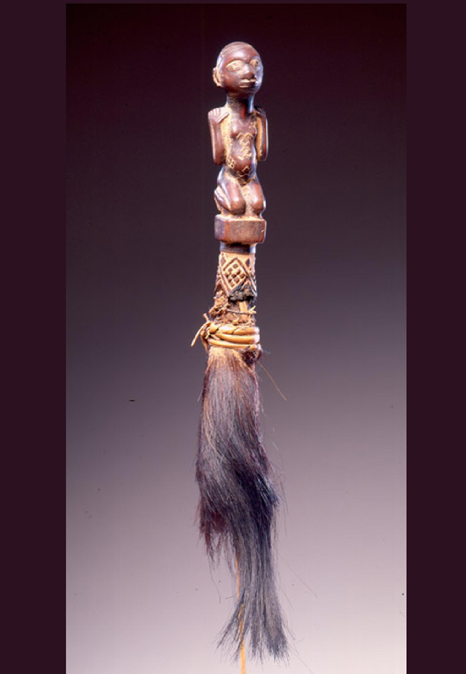

Kongo Artist, Vili Region

Kongo Artist, Vili Region

Democratic Republic of the Congo or

Republic of the Congo

“Fly Whisk”

Nineteenth century or earlier

Wood, hair, and raffia

13¾ x 2 x 2 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

1984.308

This fly whisk was used as an emblem of political office. Its smooth, worn surfaces show signs of extensive use.

Delicate metalwork ornaments the figure’s face, repeating the same sign at the center of her forehead and at both temples. These four points mark the Dikenga, the Kongo cosmogram that charts the never-ending cycle of life.

Moving counterclockwise, the point at three o’clock indicates birth, twelve o’clock indicates prime of life, nine o’clock indicates the role of the elders, and six o’clock refers to the realm of the ancestors.

Pende Artist

Pende Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Cup”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

8 1/8 x 5 inches

Gift of Bernard and Patricia Wagner

2004.230

A heart-shaped face animates this cup. The face tilts slightly to one side, giving the sculpture a subtly asymmetrical expression. Its central support balances on one foot.

Pende sculptors carved such ceremonial cups to hold palm wine, a mildly intoxicating beverage made from the fermented sap of certain palm trees. Drinking palm wine was reserved primarily for initiated men.

Nsapo-Beneki, Songye Region

Nsapo-Beneki, Songye Region

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Neck Rest”

Nineteenth century

Wood

7 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.309

This neck rest, once used to support the head while resting or sleeping, was carved by an artist known to African art collectors as the Master of Beneki.

Much of his work shares signature stylistic features, especially extravagantly large feet. In Songye art as well as in the art of the neighboring Luba, Kuba, and Shilele, prominent feet symbolize power. The motif refers to the confiscation of territory in warfare. This neck rest is supported by two back-to-back figures, both with huge feet.

Luba Artist

Luba Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Divination Object” (Kashekesheke)

Early–mid twentieth century

Wood

5 1/4 x 2 1/4 x 2 7/8 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.79

During divination sessions, a diviner and client held this sculpture and inserted their fingers into its opening. As the sculpture was moved across the diviner’s woven mat, it produced the sound “shekesheke,” giving this divination tool its name, kashekesheke.

Through this process problems were solved, memories reconstructed, and reasons for histories of misfortune revealed. Kashekesheke is one of the oldest of all Luba divination techniques.

Mangbetu Artist

Mangbetu Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Vessel”

ca. 1910

Terracotta 12 1/2 × 6 × 6 inches

Purchase in honor of Debbie Wagner, President of the Members Guild, 2002–2003 2003.36

This intricately detailed anthropomorphic vessel was made as a prestigious gift. Its elegant form depicts the aristocratic hairstyle worn by royal men and women of the Mangbetu kingdom in central Africa at the turn of the century. By the early 1920s the Belgian Queen Elizabeth visited central Africa and photographed a woman of the Mangbetu court; her portrait was then circulated on the Belgian stamp and images of royal Mangbetu women proliferated throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The image became an important icon for Harlem Renaissance artists, inspiring Aaron Douglas’s cover image for Opportunity magazine and many other works.

Kwese Artist

Kwese Artist

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Helmet Mask”

Twentieth century

Wood and pigment

12 1/4 x 9 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.85

The white paint on the face of this mask identifies it as a representative of ancestral and spiritual realms. In Kwese society, sacred masks kept in small communal shrines perform at initiation ceremonies and on other occasions to promote social well-being, health, and abundance.

This mask’s costume would have included a large, full collar of raffia fiber. Kwese masks are so similar to those of their neighbors the Yaka, the Suku, and the Pende that they are often misattributed.

This mask’s red, blue, and white polychrome and its vertical crest distinguish it as Kwese.

Kongo Artist, Yombe Region

Kongo Artist, Yombe Region

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola

“Scepter”

Nineteenth century

Wood, feathers, cloth, paint, and metal

17 3/4 × 9 1/2 × 5 inches

Purchase with funds from the Fred and Rita Richman Special Initiatives Endowment Fund for African Art

2005.291

The figure seated at the center of this royal scepter is painted white to show that its authority derives from ancestral and spiritual realms. The stroke of earth-red paint on its torso symbolizes life’s vital force.

The feathers that surround the figure at the center of this scepter indicate that it is an nkisi, a medicine of God, concerned with “things of the above.” With a hand raised to its mouth, the figure bites munkwisa, a tenacious plant used in the investiture of Kongo political leaders.

Munkwisa leaves are associated with an ability to endure.

Kongo Artist, Yombe Region

Kongo Artist, Yombe Region

Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Republic of the Congo, or Angola

“Mother and Child Figure”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood, brass tacks, and glass

12 3/4 × 4 1/4 × 4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.293

This sculpture was made to be used within the context of Mpemba, an organization concerned with fertility and the treatment of infertility, founded by a famous Kongo midwife.

The female figure’s studded cap, chiseled teeth, and scarification indicate her aristocratic status. Both the brass tacks and the glass eyes were imported. The light-reflecting glass was associated with an ability to see into invisible spiritual and ancestral realms.

BURKINA FASO

Bura Artist

Bura Artist

Burkina Faso

“Vessel”

third–eleventh century

Terracotta, 16 x 5 inches

Gift of Harriet and Eugene Becker

2004.240

Located along the Niger River in present-day Niger and Mali, the ancient sites of the Bura culture have been excavated by researchers and found to include areas dedicated to burials and other rituals as well as zones used for habitation. Some of the most striking discoveries involved the unearthing of huge cemeteries such the one at Asinda-Sikka, where 630 terracotta containers similar to this object were found.The vessels had been buried with their mouths facing down, and many contained an iron arrowhead. Their placement marked the burial of human remains a few feet further down, and the containers took both figural and more abstract forms, similar to this object. The discovery of more abstract pots at sites of both ritual and domestic activity suggests that for the Bura culture, pots such as this one served multiple purposes.

Bura Artist

Bura Artist

Burkina Faso

“Vessel”

third–eleventh century

Terracotta, 16 x 5 inches

Gift of Harriet and Eugene Becker

2004.240

Located along the Niger River in present-day Niger and Mali, the ancient sites of the Bura culture have been excavated by researchers and found to include areas dedicated to burials and other rituals as well as zones used for habitation. Some of the most striking discoveries involved the unearthing of huge cemeteries such the one at Asinda-Sikka, where 630 terracotta containers similar to this object were found. The vessels had been buried with their mouths facing down, and many contained an iron arrowhead. Their placement marked the burial of human remains a few feet further down, and the containers took both figural and more abstract forms, similar to this object. The discovery of more abstract pots at sites of both ritual and domestic activity suggests that for the Bura culture, pots such as this one served multiple purposes.

Lobi Artist

Lobi Artist

Burkina Faso

“Seated Figure”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

6.25 x 5 inches

Purchase with funds from Jane Fahey and Emmet Bondurant in memory of Alan Brandt

2003.35

A miniature masterpiece, this sculpture might be seen as the Lobi version of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker. Its contemplative posture and the despairing gesture of its large hands give it emotional weight.

Known by the Lobi people as bateba, sculptures like this one were carved to act as intermediaries between people and protective sprits called thila. The sculptures are considered animate, carrying out the orders of thila, protecting individuals and communities from harm.

Lobi Artist

Lobi Artist

Burkina Faso

“Head”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

16 5/8 × 5 1/2 × 6 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2004.139

The deeply weathered surface of this elegant head, with its smooth, round forms and pure, simple lines, suggests it was once kept outdoors in the open air. Carved at the suggestion of a diviner or traditional healer as a remedy for sickness or misfortune, the sculpture represents a protective spirit. It probably once stood on a household or market altar.

GUINEA

Baga Artist

Baga Artist

Guinea

“Male and Female D’mba Figures”

Nineteenth century

Wood

26 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.284.1-2

These two d’mba figures share the same profiles as the headdresses of the masquerades performed during Baga weddings and on other joyous occasions.

For the Baga people living on the small tropical islands of coastal Guinea, d’mba is an abstract concept encompassing all that is good and beautiful in the world; it stands for a new state of being and new aspirations.

This concept is embodied in both male and female figures.

CAMEROON

Bamileke Artist, Cameroon, “Elephant Headdress”, nineteenth century. Glass beads, wood, cloth, and raffia, 17 1/2 x 23 3/8 x 20 1/8 inches. Purchase through funds provided by patrons of the Second Annual Collectors Evening, 2011. 2011.1

Bamileke Artist, Cameroon, “Elephant Headdress”, nineteenth century. Glass beads, wood, cloth, and raffia, 17 1/2 x 23 3/8 x 20 1/8 inches. Purchase through funds provided by patrons of the Second Annual Collectors Evening, 2011. 2011.1

During the nineteenth century, when this work was made, elephant masks were among the most prestigious of all the masquerades performed by groups of wealthy, titled men in the small Bamileke kingdoms of the Cameroon Grassfields. The elephant, like the leopard, was a royal symbol, though both animals have long since become extinct in Cameroon. They were also considered the alter egos of Bamileke kings, who were described as having the ability to transform into either creature at will. Elephant masks were referred to as “things of money” because they were profusely ornamented with glass beads made in Venice or Czechoslovakia.

Fang Artist

Fang Artist

Cameroon

“Male and Female Reliquary Guardian Figures”

ca. 1875–1925

Wood, ancestral relics, brass, and glass

18.25 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.291.1-2

In the dense equatorial region of central Africa, Fang sculptures like these were carved as guardian figures to sit upon bark boxes containing a family’s ancestral relics. As sentinels, the sculptures are upright, frontal, and symmetrical; they are alert and at attention. A Fang elder described how, “Their faces are strong, quiet, and reflective. They are thinking about our problems and how to help us. We see that they see.” The harmonious, balanced contours of reliquary guardian figures convey a sense of tranquility valued in both art and life in Fang culture. Their boldly geometric forms also inspired artists of early twentieth-century Paris such as Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Constantin Brancusi.

ANGOLA

Chokwe Artist

Chokwe Artist

Angola

“Mask”

Twentieth century

Wood, fiber, metal, and pigment

10 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.294

In Chokwe communities of the southern savannah region of central Africa, ancestral spirits known as makishi return to this world as animate beings to instruct the living.

During the initiations of young men, makishi take the form of masks to transmit knowledge from generation to generation.

Today ancestral spirit masks perform not only at initiations but also at political rallies, during national elections, and even outside prisons to give hope and spiritual support to inmates.

Chokwe Artist

Chokwe Artist

Angola

“Tobacco Mortar”

Nineteenth century

Wood, leather, and brass tacks

6 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.296

Bright, shiny brass tacks augment the glowing patina of this exceptionally elaborate mortar, whose support is in the form of a trader riding on an ox. During the nineteenth century, brass tacks such as these, obtained through trade with Europeans, were rare and quite costly in Chokwe communities and were associated with high social rank. Tobacco had a similar association and was reserved for elders and for men and women of privileged status. Tobacco had both social and ritual importance among the Chokwe and the neighboring peoples of central, eastern, and southern Africa. In Chokwe communities, tobacco was smoked and inhaled as snuff in ceremonial contexts to honor the memory of lineage ancestors. The Chokwe consider the act of smoking helpful in establishing communication between celebrated ancestors, guardian spirits, and living generations.

Chokwe Artist

Chokwe Artist

Angola

“Thumb Piano”

Late nineteenth to early twentieth century

Wood and metal

5 1/4 x 2 1/2 x 1 1/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.172

In Chokwe communities of the southern savannah region of central Africa, oral historians sing the praises of accomplished individuals, recount past events, and comment on current situations. The music of thumb pianos and stringed instruments often accompanies their songs. This thumb piano, decorated with a diminutive, mask-like face, is unusually small and easily portable. The thumb piano—also called an mbira, sanza, likembe, or kalimba—is played throughout much of Africa and the African Diaspora. Thumb piano music has gained international fame, popularized by musicians such as Stella Rambisai Chiwese, a Shona artist from Zimbabwe. Her music bridges two worlds; she performs the role of maridzambira, singing and playing in traditional trance rituals, while recording and appearing for international audiences. Her music is known for its extraordinary hypnotic power.

Chokwe Artist

Chokwe Artist

Angola

“Whistle”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

4 x 1 1/2 x 1 3/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.128

Chokwe men use small whistles like this to communicate with one another and with their dogs while hunting. This whistle is decorated with the image of chikunza, a mukanda mask made of barkcloth over an armature of wicker, identifiable by its tall conical headdress. Mukanda is an institution found throughout much of Central Africa, responsible for transmitting religion, art, and social organization from generation to generation. The chikunza masquerade represents a stern, old man, recognized as the father of masks, the father of initiation, and the master of the mukanda lodge, where initiation events take place. Chikunza, as protector of hunters and of women in childbirth, is associated with goodness, plenty, success, and fertility.

IVORY COAST

Senufo ArtistI

Senufo ArtistI

Ivory Coast

“Female Figure”

Nineteenth century

Wood

11 3/8 × 3 1/4 × 2 1/2 inches (28.9 cm × 8.3 cm × 6.4 cm)

Fred and Rita Richman Collection:

2002.283

As intercessors to the spirit world, Senufo diviners use sculptures like this one to secure ancestral blessings.

The beauty of these sculptures reflects the stature and prestige of diviners and their clients.

This figure’s upright posture communicates a sense of dignified authority and its clearly articulated forms have a commanding presence.

Repeated applications of palm oil make its surface glisten.

Baule Artist

Baule Artist

Ivory Coast

“Monkey-Like Figure”

Twentieth century

Wood. 38 1/2 x 10 x 13 inches

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine

75.63

Within Baule sculptural traditions, monkey-like figures such as this one serve a variety of purposes and are known by different names according to their place of origin. Such sculptures are usually no more than two feet tall—this example is unusually large—with a square muzzle, pointed teeth, and cupped hands held in front of the body. Some even grasp a cup. The sculptures are always male and typically wear a loincloth made of actual fabric. They are used for divination and for the spiritual protection of families and larger social units. Considered too powerful to be displayed publicly, their creation and use is shrouded in secrecy. In both form and function they share many similarities with the sacred masks reserved for Baule men. Both synthesize human and animal forms and are considered dangerous to women. This sculpture, while roughly hewn, is carved with considerable expressive force.

Dan Artist

Dan Artist

Ivory Coast or Liberia

“Mask”

Twentieth century

Wood

10 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2002.300

In Dan communities of Liberia and the Ivory Coast, masks are performed only by men. This mask may have performed as deangle (“joking or laughing masquerade”), the mask of the initiation school, whose friendly, attractive spirit brings joy.

Through graceful movements, it personifies a nurturing female spirit who provides food for boys living away from home in initiation camps.

GHANA

Akan Artist

Akan Artist

Ghana

“Double-Figured Staff Finial”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood, brass tacks, white beads, and fiber

19 1/2 × 1 3/4 × 1 3/4 inches

Purchase with funds from Fred and Rita Richman

2009.25

This finial was once situated atop a staff that was used as a portable shrine to commemorate ancestors.

In Akan culture, ancestors look over their descendents and promote their well-being. The upper, bearded figure represents an ancestral spirit and is seated on a standing male figure’s shoulders, serving as his guide.

In Baule communities of the Ivory Coast, to be possessed is to have a spirit “fall upon” one. The possessed person is “ridden,” guided by the ancestral spirit.

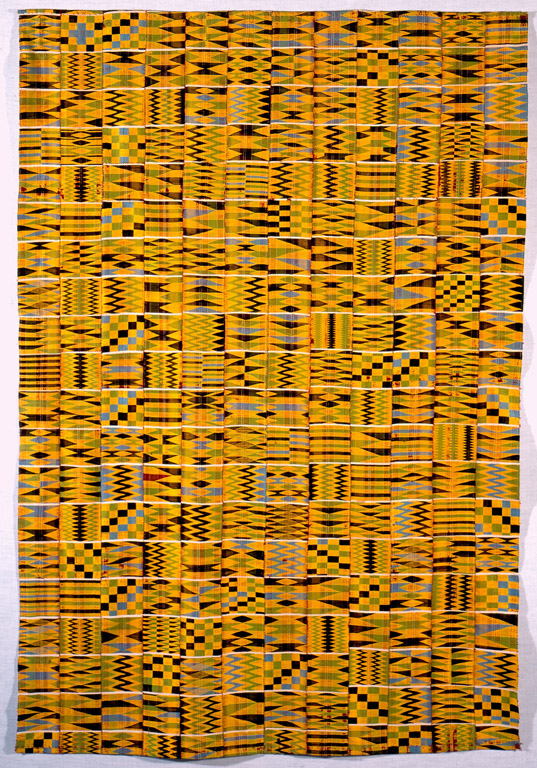

Asante Artist

Asante Artist

Ghana

“Kente Cloth”

ca. 1900–1925

Silk

38 1/2 x 55 1/2 inches

Purchase with funds from Fred and Rita Richman

2004.166

The brilliantly colorful, geometric patterns of this silk kente cloth fragment express a highly refined, strongly musical aesthetic sensibility that is at once subtle and sublime.

One red accent floats across a rich field of rhythmically complex patterns in yellow, green, blue, black, and white. An exceptionally fine example of kente cloth, this section is from a much larger cloth called oyokoman adweneasa. Oyokoman is the name of the striped pattern of the ground weave in the warp threads.

Made primarily of wide, dark red stripes on this cloth, the oyokoman pattern is considered the first and most elite of all kente patterns and has the longest and most complex history.

Asante Artist

Asante Artist

Ghana

“Mother and Child Figure”

Twentieth century

Wood, pigment, beads, and metal

14 x 5 x 6 1/2 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

1984.302

In Asante communities, mother and child sculptures are placed on the family shrines of both royalty and commoners.

They serve a protective function while promoting the continuity of the family’s lineage, as Asante inheritance descends through the maternal line. In this statue, the mother feeds her child from her breast while seated on a stool.

Her elaborate coiffure and jewelry suggest a royal status, indicating that she may be either a priestess or a queen mother—the most senior female of a lineage—seated in state for a formal occasion.

Her carved sandals further substantiate her elite social position.

Osei Bonsu (Asante, Ghana, 1900-1977)

Osei Bonsu (Asante, Ghana, 1900-1977)

“Ntan Drum”

Mid-late 1930s

Wood and paint

Gift of Fred and Rita Richman, 2011.158

SIERRA LEONE

Mende Artist

Mende Artist

Sierra Leone

“Helmet Mask”

ca. 1875-1925

Wood

14 3/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

72.40.22

In Mende communities of the tropical forests of Sierra Leone, unlike elsewhere in Africa, both men and women dance masks.

Helmet masks called sowei are worn by members of the exclusively female Sande society—a politically powerful women’s organization—to teach young girls how to be good wives and mothers and productive community members. Sowei helmet masks represent one of the few instances in which masks are used exclusively by and for African women.

They represent Mende ideals of feminine beauty. The lustrous black surface of this mask is richly textured. It wears a British-style royal crown and has a full, ringed neck decorated with rows of carved Islamic amulets. Its delicately detailed, diamond-shaped face is surrounded by an elaborately interwoven coiffure.

Mende Artist

Mende Artist

Sierra Leone

“Mask”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood and raffia. 18 x 13 inches

Gift of Bernard and Patricia Wagner

2006.227

This Mende mask is a source of inspiration to Atlanta-based artist Radcliffe Bailey as revealed in his recent exhibition Radcliffe Bailey: Memory as Medicine. In 2006, DNA test results informed the artist that, on his mother’s side of the family, his ancestors came from the Mende region of Sierra Leone and nearby areas of West Africa.

This information inspired Bailey to create a diminutive “family portrait”—an ink drawing of a Mende mask framed within a velvet-lined tintype case. More recently, Bailey printed the image of this Mende mask in full color on a steel plate, positioning the actual mask to be reflected onto its surface. This installation juxtaposed the ancestral world and the present day, collapsing the confines of time.

REPUBLIC OF BENIN

Fon Artist, Kingdom of Dahomey, Republic of Benin, “Staff”. Late nineteenth–early twentieth century. Wood and brass, 15 inches. Fred and Rita Richman Collection. 2002.286

Fon Artist, Kingdom of Dahomey, Republic of Benin, “Staff”. Late nineteenth–early twentieth century. Wood and brass, 15 inches. Fred and Rita Richman Collection. 2002.286

Scepters such as this one, from the Kingdom of Dahomey in the Republic of Benin, were created from war axes and symbolized the authority of their owners. The messenger of the king would carry a concealed staff on his shoulder and uncover it only in the presence of the recipient of the message in order to complete the dispatch. A horse head—a symbol of political power—is mounted to the top of this staff, while a small animal silhouette climbs up the neck.

MALI

Bamana Artist

Bamana Artist

Mali

“Door Lock”

ca. late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood

17 x 4 x 3 1/2 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

1979.40.125

This sculpture once secured a crossbar that held a door lock in place and provided its owners with physical and spiritual security. It is constructed from two pieces of wood placed crosswise, with an internal mechanism activated by a serrated key made of metal or wood. The lock’s severe, geometric forms contrast with the intricately incised marks that adorn its surfaces. The sophisticated task of manufacturing door locks was the responsibility of blacksmith-sculptors—always men—who in Bamana societies inherit the right to work with wood and metal. The finished locks were used on the doors of homes, granaries, cookhouses, and sanctuaries, and often carried the signature artistic style of their particular maker. Though utilitarian in nature, each Bamana lock is conceived as an autonomous object and is given a name that corresponds with the figure, message, or myth that it represents.

Dogon Artist

Dogon Artist

Mali

“Male and Female Figures”

Late nineteenth–early twentieth century

Wood. 17 3/4 inches

Fred and Rita Richman Collection

2004.144-145

Male and female pairs such as these two sculptures are placed on altars to secure ancestral blessings. The paired figures also recall the primordial couple described in Dogon oral histories and creation myths from whom all subsequent generations descended. The rather severe, abstract forms of these two figures echo one another.

The proportions of their torsos and arms are elongated and their legs are compressed. The female figure balances a vessel on her head, a reminder of women’s quotidian duties as bearers of water, a precious resource for communities living at the edge of the Sahara Desert.

Djenne Artist

Djenne Artist

Mali

“Male Figure”

Thirteenth–fifteenth century

Terracotta

21 3/4 × 10 × 8 inches

Purchase with funds from the Fred and Rita Richman Special Initiatives Endowment Fund for African Art

2007.114

This powerfully expressive, elegant figure, with its face tilted toward the heavens, comes from the region of the ancient city of Djenne, in Mali, West Africa. Djenne is considered the most ancient city in sub-Saharan Africa, founded more than 2,000 years ago. Today the entire city, which includes the Great Mosque, whose foundations date to the thirteenth century, is a UNESCO World Heritage site. This sculpture is closely related to a set of large, stylistically similar terracotta figures. Now a fragment, it may once have consisted of a full figure, seated and kneeling in prayer or riding a horse. As evidenced by thermoluminescence tests completed in 1988, it was created between ca. 1300 and 1500, when the medieval Empire of Mali encompassed much of what is now West Africa, from Mali to the coast of Senegal. Both this sculpture and the Great Mosque are made of earth—red, like Georgia’s soil.

Bamana Artist

Bamana Artist

Mali

“Boli Figure”

Twentieth century

Mixed media

28 inches

Anonymous gift

2005.316

Boli sculptures are sacred objects of the Bamana culture that can take many organic forms, including this example of a human figure. They are not carved, but rather assembled and molded from materials such as clay, wood, bark, millet, and honey.

The sculptures are often enlarged and reworked with the residue from sacrifices and rituals. Boli are used as altars by the Komo Society, a men’s association of priests, elders, and blacksmiths that forms the primary Bamana social group. Sequestered in shrines or in the dwellings of priests, the boli’s amorphous form keeps its sacred secrets hidden from the uninitiated.

These dark, textured sculptures are disquieting and powerful objects, even when far removed from their original home.

SOUTH AFRICA

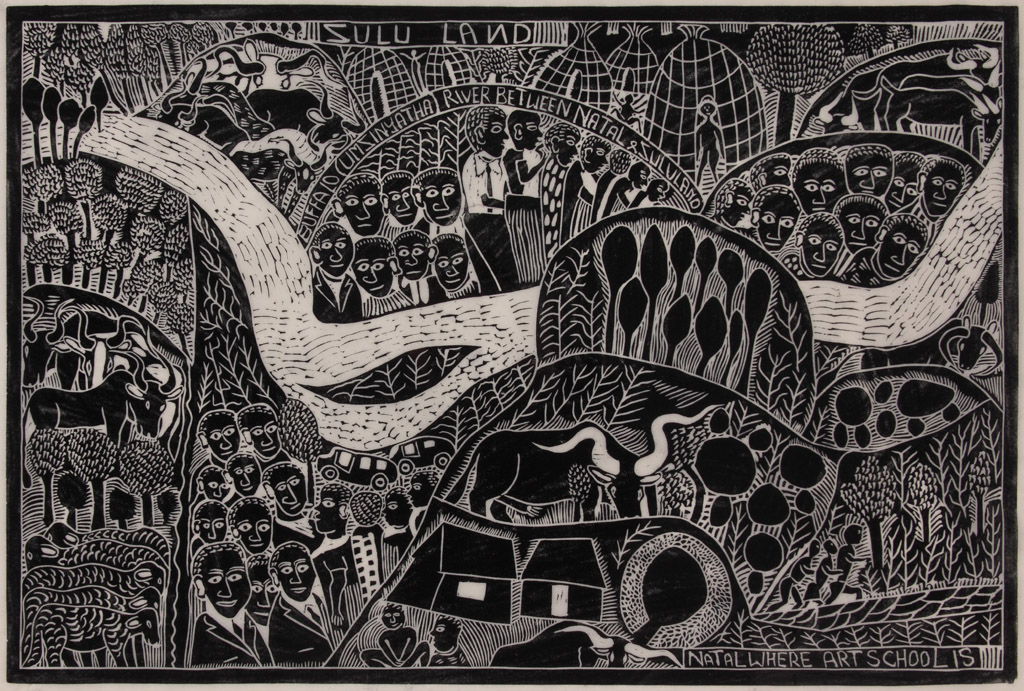

John Muafangejo, Namibian, 1943-1987, “Natal Where Art School Is”, 1974, Linocut, 27 1/4 x 18 1/4 inches.

John Muafangejo, Namibian, 1943-1987, “Natal Where Art School Is”, 1974, Linocut, 27 1/4 x 18 1/4 inches.

Anonymous gift. 2005.321

John Muafangejo’s print Natal Where Art School Is highlights the political transition from non-violent protests to armed resistance in the 1970s. The work’s stylized imagery and textual embellishments are characteristic of art produced at Rorke’s Drift Art Centre, where Muafangejo trained. Established in Natal in southeastern South Africa in 1962, Rorke’s Drift played a central role in the development of Black art and craft in the 1960s and 1970s.

Statement

Carol Thompson

Carol Thompson

The Fred and Rita Richman curator of African art at the High.

“Featuring works from ancient to contemporary times and from disparate regions throughout the continent, all of which were acquired over the last nine years, African Art: Building the Collection provides important insights into African cultural heritage from the past to the present day.”

“Presented together, this extraordinary group of objects represents a diverse range of artistic expressions from African nations including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Benin, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, South Africa and South Sudan”.

“We are so incredibly grateful for the generosity and support Fred and Rita Richman have shown the High over the past 42 years,”

SEE ALSO ABOUT AFRICAN ART:

MAGDALENE ODUNDO

High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree Street, N.E., Atlanta, GA 30309

24-hour Recorded Info 404-733-4444

www.high.org

About the High Museum of Art

The High is the leading art museum in the southeastern United States. With more than 15,000 works of art in its permanent collection, the High Museum of Art has an extensive anthology of 19th- and 20th-century American art; a substantial collection of historical and contemporary decorative arts and design; significant holdings of European paintings; a growing collection of African American art; and burgeoning collections of modern and contemporary art, photography, folk and self-taught art, and African art. The High is also dedicated to supporting and collecting works by Southern artists. Through its education department, the High offers programs and experiences that engage visitors with the world of art, the lives of artists and the creative process.