CHILDREN TO IMMORTALS

Figural Representations in Chinese Art

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Until January 3, 2021

Panel with boys at play late 16th–early 17th century (detail) 清 緙絲百子圖

HIGHLIGHTS

The first gallery of the exhibition focuses on children, a ubiquitous and

long-standing motif expressing the cultural importance of offspring.

The second gallery displays scenes from idealized daily life, historical novels, and legends. In the third gallery religious figures of Buddhism and Daoism are presented.

Conveying a person’s inner spirit (chuanshen) is the central aspect of figural representation in Chinese art. Rather than prioritizing accurate anatomical renderings, artists sought to capture the “life energy” of their subjects.

The exhibition explores sophisticated decorative arts that depict figures dating to late imperial China, from the Song (960–1279) to the Qing (1644–1911) dynasty. Over this thousand-year period, images of humans, legendary figures, and immortals frequently appeared.

Some of the objects in this exhibition are recognized masterpieces, while others are little known and have not been on view for decades. Mainly drawn from The Met collection, this exhibition showcases diverse media, including textiles, lacquer, jade, ceramic, wood, bamboo, and metalwork.

Purse with boys playing, 10th–11th century

遼 嬰戯紋織錦囊

Purse with boys playing. Liao dynasty (907–1125) 10th–11th century, China. Silk weft-faced compound twill, 5 5/8 x 5 3/8 x 1 in. (14.3 x 13.7 x 2.5 cm) Eileen W. Bamberger Bequest, in memory of her husband, Max Bamberger, 1996.

Purse with boys playing. Liao dynasty (907–1125) 10th–11th century, China. Silk weft-faced compound twill, 5 5/8 x 5 3/8 x 1 in. (14.3 x 13.7 x 2.5 cm) Eileen W. Bamberger Bequest, in memory of her husband, Max Bamberger, 1996.

Comments: “On the back of this purse, boys run and tumble, surrounded by flowers, plants, birds, and deer. Woven freely into the silk, this design is an early example of children at play, a form that can be traced to Central Asia in the eighth century. The silk’s pattern is clearly scaled to fit small objects such as this purse”.

Textile fragment with boys in floral scrolls, 11th–12th century

北宋 嬰戯紋綾

Textile fragment with boys in floral scrolls, 11th–12th century. Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) China. Silk twill damask (ling), W. 11 1/2 in. (29.2 cm); L. 13 in. (33 cm) Rogers Fund, 1952

Comments: “This textile was meticulously woven with boys tucked among floral scrolls and lotus pods—a rebus for, or visual allusion to, progeny. In addition to the Buddhist belief in rebirth from the lotus, multiseeded lotus pods were also thought to be a symbol for plentiful offspring”.

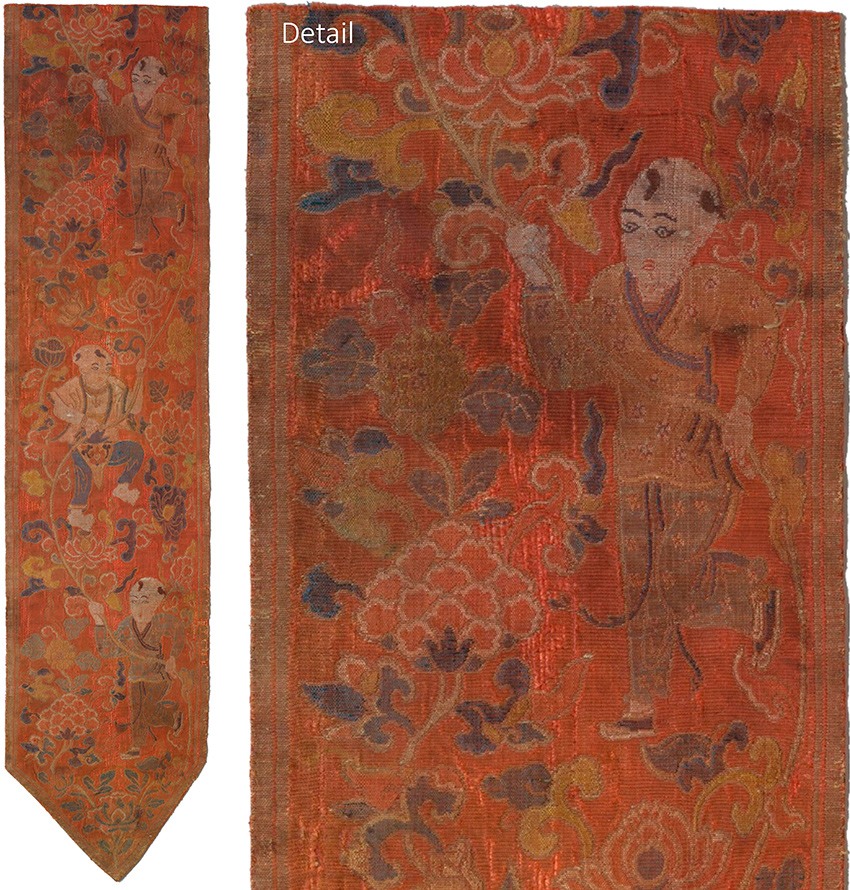

Vertical pendant with boys holding a lotus scroll, 13th–14th century

元 童子戯蓮紋羅

Vertical pendant with boys holding a lotus scroll, 13th–14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) 13th–14th century, China. Complex gauze with silk and metal thread weft patterning, 11 x 46 1/2 in. (27.9 x 118.1 cm) Mount: 51 1/2 x 13 1/2 in. (130.8 x 34.3 cm) Joseph E. Hotung Gift, 1987

Comments: “Remarkable for its large size and fresh colors, this textile was woven with the typical Chinese motif of boys and lotuses. However, details on certain costumes reveal a Mongolian influence. The jackets of the boys seen at top and bottom are fastened on the figures’ left, a style not used in Chinese clothing. The design of the large flower blossom and the color palette also help to date it to the Yuan period, when China was under Mongol rule”.

Children playing in the palace garden, late 13th–15th century

元末明初 佚名 絹本設色 嬰戯圖 軸

Children playing in the palace garden, late 13th–15th century. Unidentified Artist Chinese. late Yuan (1271–1368)–early Ming (1368–1644) dynasty, China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk, Image: 54 7/8 x 30 in. (139.4 x 76.2 cm) Overall with mounting: 113 1/2 x 36 1/2 in. (288.3 x 92.7 cm) Overall with knobs: 113 1/2 x 39 in. (288.3 x 99.1 cm) The Dillon Fund Gift, 1987.

Children playing in the palace garden, late 13th–15th century. Unidentified Artist Chinese. late Yuan (1271–1368)–early Ming (1368–1644) dynasty, China. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk, Image: 54 7/8 x 30 in. (139.4 x 76.2 cm) Overall with mounting: 113 1/2 x 36 1/2 in. (288.3 x 92.7 cm) Overall with knobs: 113 1/2 x 39 in. (288.3 x 99.1 cm) The Dillon Fund Gift, 1987.

Comments: “Twenty-two boys play games, ride hobbyhorses (a toy that may have been invented in China), and enjoy a large masonry slide in the corner of an imperial garden. Children at play was a popular subject among artists of the earlier Song Imperial Painting Academy. Judging from the costumes and representational techniques, this painting was most likely executed in the first years of the Ming dynasty, when the imperial court revived the styles and subjects of the academy”.

Tray with women and boys on a garden terrace, 14th century

元 剔紅仕女嬰戲圖漆盤

Tray with women and boys on a garden terrace, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) 14th century, China. H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm); Diam. 21 7/8 in. (55.6 cm). Lacquer, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015

Tray with women and boys on a garden terrace, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) 14th century, China. H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm); Diam. 21 7/8 in. (55.6 cm). Lacquer, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015

DETAIL of Tray with women and boys on a garden terrace

Comments: “Scenes of harmonious families featuring women and frolicking children began to appear in Chinese decorative art in the fourteenth century. This tray depicts two women and twenty-three boys on a terrace and pavilion overlooking a lotus pond. One woman, clearly the hostess, rests on an openwork seat; the other, probably a nanny, holds one child while another clutches her skirt. Several other youth take part in a procession that resembles that of court officials—a common sight in major Chinese cities in the fourteenth century”.

Panel with boys at play, late 16th–early 17th century

清 緙絲百子圖

Panel with boys at play, Ming dynasty (1368–1644) late 16th–early 17th century, China. Silk and metal thread tapestry (kesi), Overall: 18 1/4 x 15 in. (46.4 x 38.1 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1936

Comments: “This textile is probably a portion of a much larger piece, perhaps a hanging, that would have illustrated many groups of small boys at play in a garden. Items bearing this popular theme were particularly favored as wedding gifts, for the boys symbolize increase, abundance, and future happiness”.

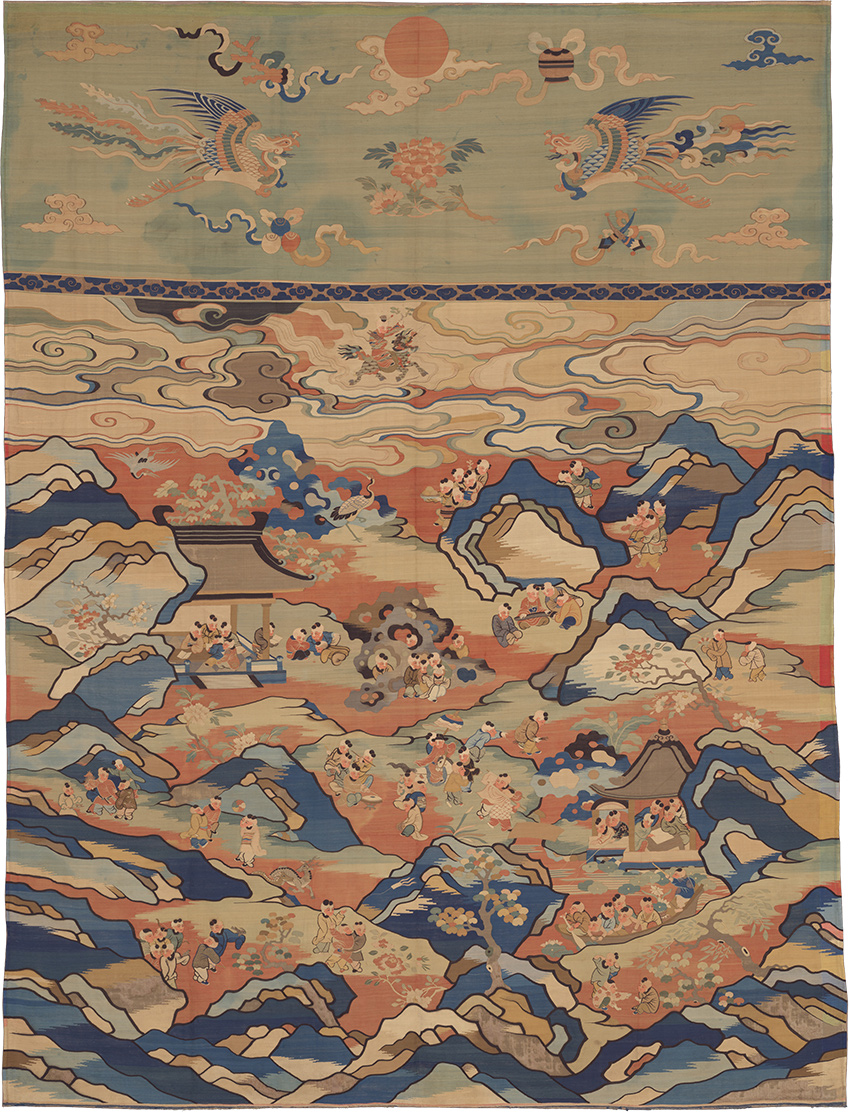

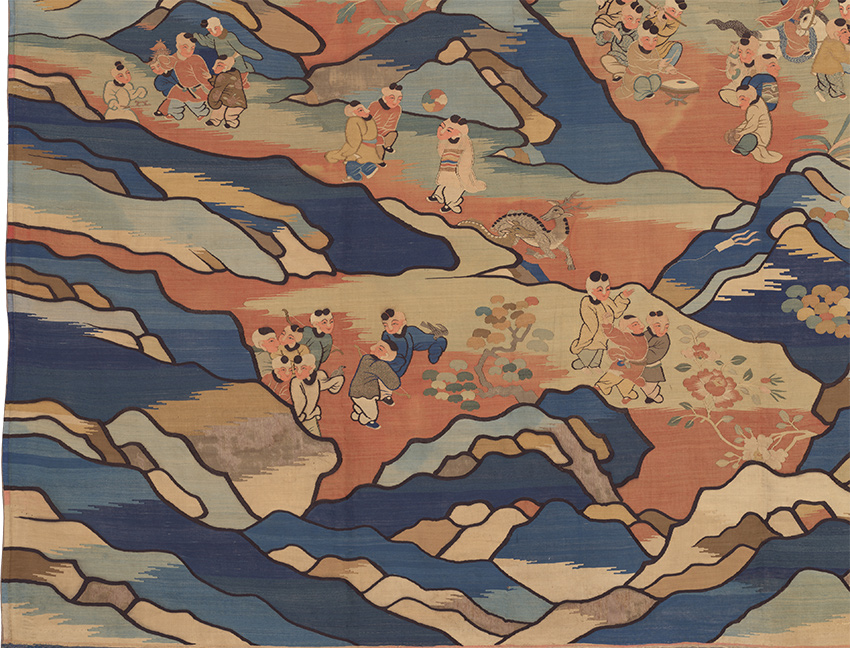

Panel with boys at play, 17th century

清 緙絲百子圖

Panel with boys at play, 17th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), China. Silk, metallic thread, and feather thread tapestry, 89 × 68 3/4 in. (226.1 × 174.6 cm). The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift, 2011.

Panel with boys at play, 17th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), China. Silk, metallic thread, and feather thread tapestry, 89 × 68 3/4 in. (226.1 × 174.6 cm). The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift, 2011.

DETAIL of Panel with boys at play, 17th century

Comments: “This large polychrome silk tapestry features a motif called “the hundred boys,” an expanded version of children at play, to express the desire for a prosperous family. Little boys (eighty-three, to be exact) engage in various activities, such as archery, boating, falconry, fishing, horseback riding, kite flying, music making, playing with a ball, and reading. Each child is woven in a different posture with simple but fluid outlines, which required not only great skill but also an artistic sensibility. Panels like this usually served as wall decoration in elite houses”.

Bowl with children in a garden, mid-16th century

清 緙絲百子圖

Bowl with children in a garden, mid-16th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Jiajing mark and period (1522–66). China. Porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware) H. 6 in. (15.2 cm); Diam. of mouth 12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm). Gift of Denise and Andrew Saul, 2001.

Bowl with children in a garden, mid-16th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Jiajing mark and period (1522–66). China. Porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware) H. 6 in. (15.2 cm); Diam. of mouth 12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm). Gift of Denise and Andrew Saul, 2001.

Comments: “The theme of boys playing was popular in Chinese decorative arts, as demonstrated by this blue-and-white porcelain bowl. Unlike carving and weaving, brush painting on porcelain gives artists more freedom to represent a variety of children’s facial expressions: delighted, charming, and sometimes mischievous”.

Base of a pillow in the form of a boy, 11th–12th century

北宋 定窯孩兒枕

Base of a pillow in the form of a boy, 11th–12th century Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) China. Porcelain with ivory white glaze (Ding ware), H. Incl. base 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); W. 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm); L. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm), Gift of Stanley Herzman, in memory of Adele Herzman, 1991.

Base of a pillow in the form of a boy, 11th–12th century Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) China. Porcelain with ivory white glaze (Ding ware), H. Incl. base 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); W. 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm); L. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm), Gift of Stanley Herzman, in memory of Adele Herzman, 1991.

Dish with scene of a family, early 18th century

清 景德鎮窯青花嬰戯盤

Dish with scene of a family, early 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware), H. 7/8 in. (2.2 cm); Diam. of rim 10 in. (25.4 cm); Diam. of foot 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm). Purchase by subscription, 1879.

Comments: “Scenes of children and families, like the one on this porcelain dish, became increasingly popular during the Qing dynasty. The central scene represents an intimate moment in which a man seated in the hall of a two-story house watches his wife and two boys play in a walled garden”.

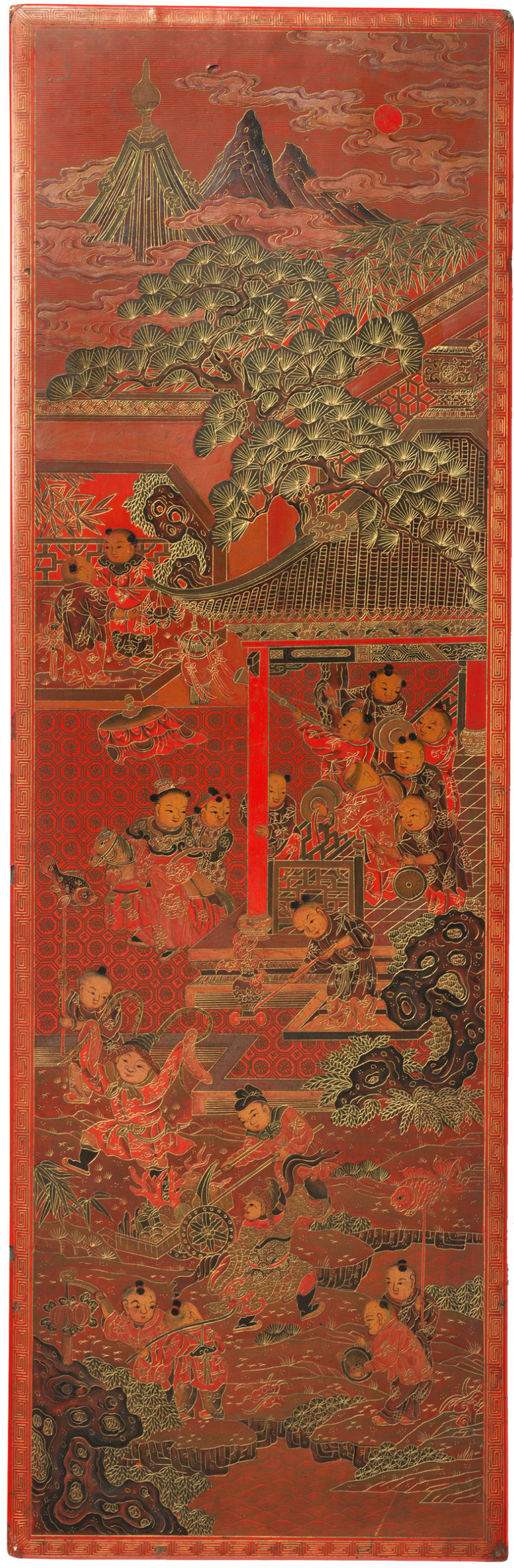

Box with boys at play,19th century

清 紅漆戧金嬰戯圖蓋盒

Box with boys at play, 19th century, : Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Red lacquer with incised decoration inlaid with gold, H. 10 in. (25.4 cm); W. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm); L. 30 1/4 in. (76.8 cm). Bequest of Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881.

Panel with birthday celebration, 19th century

清晚期 緙絲賀壽圖

Panel with birthday celebration, 19th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), China. Silk tapestry (kesi), Overall (top panel): 52 3/8 x 122 5/16 in. (133 x 310.7 cm). Gift of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1954.

Panel with birthday celebration, 19th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), China. Silk tapestry (kesi), Overall (top panel): 52 3/8 x 122 5/16 in. (133 x 310.7 cm). Gift of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1954.

Comments: “This tapestry is part of a set of large ornamental panels. Among the guests honoring the elderly couple are several lively children, probably their grandsons. The man and his wife wear matching robes, appropriate dress for court officials and their wives. As a birthday gift, the three boys at their feet present a hanging scroll bearing the character for longevity (shou) in blue, surrounded by five red bats (fu). Bats were typically used to represent good fortune, as the words are homophones in Chinese”.

Tray with scholars, 15th century

明 黑漆嵌螺鈿學士圖八方盤

Tray with scholars, 15th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay, H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); Diam. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); Diam. of foot 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm). H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); Diam. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); Diam. of foot 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm).

Tray with scholars, 15th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay, H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); Diam. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); Diam. of foot 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm). H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); Diam. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); Diam. of foot 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm).

Comments: “This dish depicts Chinese literati, or scholar-officials, engaging in leisure activities. In the foreground, three such men, identifiable by their clothing, travel on horseback toward a gate attended by two figures holding large fans. The trio in the middle ground examines a painting displayed by a pair of young attendants. The other scholars are either strolling in the garden, reading books, enjoying tea, or engaged in conversation”.

Brush holder with scholars in a garden, 18th century

清乾隆 剔紅西園雅集圖筆筒

Brush holder with scholars in a garden, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95). China. Carved red lacquer, H. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm); Diam. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015.

Brush holder with scholars in a garden, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95). China. Carved red lacquer, H. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm); Diam. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015.

Comments: “This brush pot shows scholars writing, painting, and enjoying nature—activities found in imagery of scholar-officials throughout Chinese art. The scene also recalls famous historical gatherings of learned men such as those in the West Garden, an eleventh-century imperial family residence”.

CHILDREN WITH IMMORTALS

Representations of immortals in Chinese art commonly include children

God of Longevity (Shoulao) with children, 18th century

清 竹雕童子壽老

God of Longevity (Shoulao) with children, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Bamboo, H. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm); W. 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm); D. 5 in. (12.7 cm). Gift of Ellen Barker, 1942.

God of Longevity (Shoulao) with children, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Bamboo, H. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm); W. 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm); D. 5 in. (12.7 cm). Gift of Ellen Barker, 1942.

Comments: “The God of Longevity (Shoulao), shown here accompanied by children, is one of the three most popular deities in Chinese folklore. The other two are gods of good fortune and achievement and distinction. Abundant in nature and desirable for carving, bamboo is frequently used both as a material and a subject matter in Chinese art from this period. Its resilience is often compared to the virtue of those who maintain their principles in the face of adversity, and its hollow stalk is often associated with humility and an unprejudiced mind”.

God of Longevity (Shoulao) and boy, 19th century

清晚期 緙絲壽老仙童圖

God of Longevity (Shoulao) and boy, 19th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Hanging scroll; silk tapestry (kesi), 32 x 18 1/2 in. (81.28 x 46.99 cm). John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1913.

Comments: “The boy in this tapestry hanging scroll is an immortal servant. The bald old man with a prominent forehead is the God of Longevity (Shoulao), and the plate of peaches in the boy’s hands a symbol of immortality”.

Fairy and immortal boy, 19th century

清 珊瑚女仙童子

Fairy and immortal boy, 19th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Coral, H. 9 3/16 in. (23.3 cm). Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950.

Fairy and immortal boy, 19th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Coral, H. 9 3/16 in. (23.3 cm). Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950.

IMMORTALS

Daoist immortal Laozi, dated 1438

明早期 陳彥清造鎏金銅老子像

Daoist immortal Laozi, Chen Yanqing (active 15th century) Ming dynasty (1368–1644) China. Gilt brass; lost-wax cast, H. 7 1/2 in. (19 cm); W. 4 3/4 in. (12 cm); D. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 1997.

Daoist immortal Laozi, Chen Yanqing (active 15th century) Ming dynasty (1368–1644) China. Gilt brass; lost-wax cast, H. 7 1/2 in. (19 cm); W. 4 3/4 in. (12 cm); D. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 1997.

Comments: “Identified by his full beard, Laozi (also known as the Celestial Worthy of the Way and Its Virtue) is the quasi-historical author of the seminal Daoist text, the Daodejing (The Way and Its Power). Daoism, a major religion in China that can be traced to the sixth century B.C., is a term used to define an amalgamation of beliefs and practices that includes metaphysical and philosophical speculations as well as guidance for everyday life”.

Laozi crossing the Han Pass, 18th century

清 玉雕老子出關山子

Laozi crossing the Han Pass, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Jade (nephrite), H. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm); W. 10 1/2 in. (26.6 cm); L. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm). Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902.

Laozi crossing the Han Pass, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Jade (nephrite), H. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm); W. 10 1/2 in. (26.6 cm); L. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm). Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902.

Comments: “Carved in deep relief, this object depicts Laozi, the celebrated founder of Daoism, on his way to visit Xi Wang Mu, the Queen Mother of the West. She rides on a floating cloud while awaiting his arrival”.

Covered vase with immortals, 18th–19th century

清 玉浮雕群仙瓶

Covered vase with immortals, 18th–19th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Jade (nephrite) a, b: H. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm); a–c: H. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); W. 4 3/4 in. (12.1 cm). Alfred W. Hoyt Collection, Bequest of Rosina H. Hoppin, 1965.

Covered vase with immortals, 18th–19th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China. Jade (nephrite) a, b: H. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm); a–c: H. 11 3/8 in. (28.9 cm); W. 4 3/4 in. (12.1 cm). Alfred W. Hoyt Collection, Bequest of Rosina H. Hoppin, 1965.

Tray with Daoist figures, 16th century

明 黑漆嵌螺鈿八仙賀壽圖托盤

Tray with Daoist figures,16th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; basketry sides, H. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm); W. 18 3/8 (46.7 cm); D. 11 5/8 (29.5). Barbara and William Karatz Gift, 2006.

Tray with Daoist figures,16th century, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; basketry sides, H. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm); W. 18 3/8 (46.7 cm); D. 11 5/8 (29.5). Barbara and William Karatz Gift, 2006.

Comments: “The eight figures assembled on the riverbank represent the Eight Immortals, a group of Daoist deities who originated from the legends of the Tang dynasty (618–907). They can each be identified by their personal attributes, including the flute, staff, sword, flower, and gourd. Here, they await the arrival of Shoulao, God of Longevity, who is flying above the waves on the back of a crane. Daoism gained increasing popularity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and so did its imagery. This exquisitely decorated tray is a remarkable example”.

Immortals of Harmony and Happiness, 18th century

清 琥珀寒山拾得像

Immortals of Harmony and Happiness, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Amber, H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm). Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950.

Immortals of Harmony and Happiness, 18th century, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Amber, H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm). Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950.

Comments: “These two figures are known as the Immortals of Harmony and Happiness (He-He Erxian). According to legend, they were originally two monks, Hanshan and Shide, who resided in the Guoqing Monastery, on the Tiantai Mountain, Zhejiang Province, during the Tang dynasty (618–907). They later became immortalized in folklore and were widely accepted as symbols of harmony and long-lasting friendship”.

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10028 Phone: 212-535-7710

https://www.metmuseum.org/