Founding Figures:

Copper Sculpture from ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

ca. 3300–2000 B.C.

May 13 through August 21, 2016

THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM

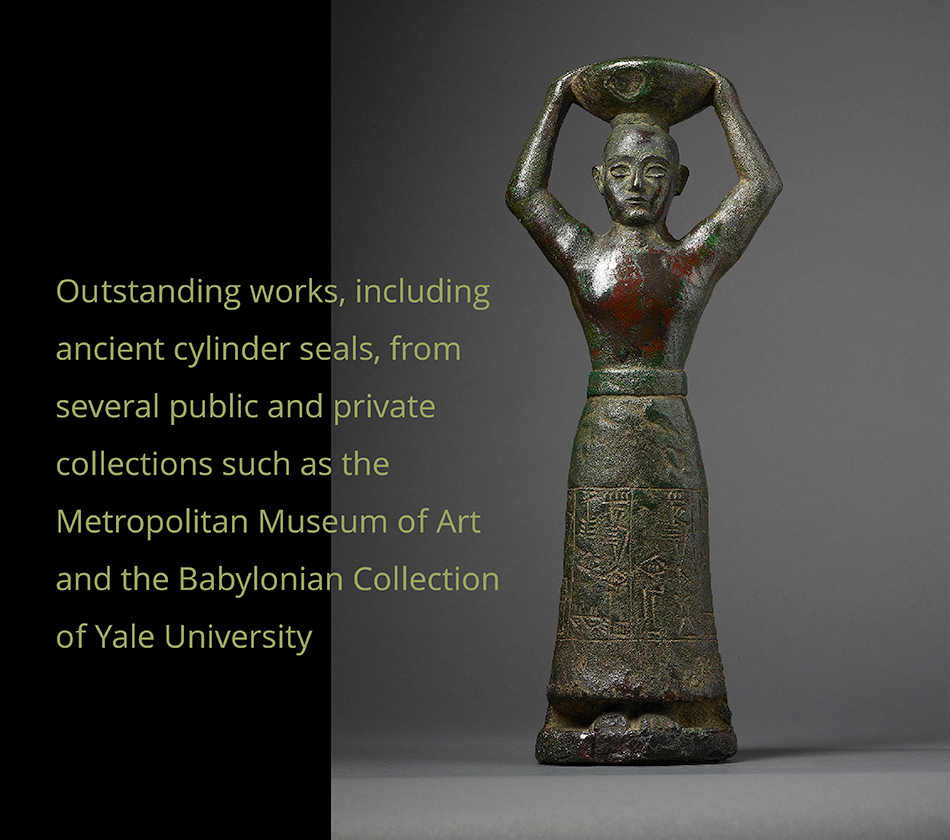

Foundation Figure of King Ur-Namma Neo-Sumerian, Ur III period, reign of Ur-Namma, ca. 2112–2094 B.C. Inscribed in Sumerian, Ur-Namma, King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, who built the temple of Enlil. Copper alloy. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

Perhaps only intended for the gods

Standing about a foot tall, the small yet monumental “foundation figures” in ancient Mesopotamia were not created to be seen by mortal eyes. Cast in copper and placed beneath the foundation of a building, often a temple, they were intentionally buried from prying humans. They combine both abstract and natural forms and were created at the behest of royal rulers concerned with leaving a record of their humanity, deeds, and civilization.

Exhibition Highlights

Morgan’s own Foundation Figure of King Ur-Namma serving as centerpiece.

Morgan’s own Foundation Figure of King Ur-Namma serving as centerpiece.

The show demonstrates how the medium of copper allowed sculptors to explore a variety of forms with a fluidity not available in traditional stone, resulting in figures of exceptional grace and delicacy. The exhibition also includes enlarged impressions of scenes engraved on cylinder seals, maps, and other visual tools to provide visitors historical and cultural context.

The Morgan’s Foundation Figure of King Ur-Namma features an inscription that mentions Enlil who was the major god of the Mesopotamian pantheon. The king’s artisans created a new type of full figure sculpture to commemorate Ur-Namma’s involvement in the construction of Enlil’s temple. The king is shown wearing a long skirt upon which the inscription is prominently featured.

His torso is bare and his head and beard are shaved in preparation for ritual. The figure demonstrates a restrained naturalism and calmness and is considered to be among the finest of all foundation figures created during the third millennium B.C. Both in the gallery and on the Morgan’s website, this exceptional piece can be viewed fully in the round.

One of the earliest surviving cast copper sculptures from Mesopotamia is Figure of a Priest King. Dates to ca. 3300–3100 B.C. Although the figure’s identity and function are unclear, its great musculature and full beard suggest authority and power. The figure is depicted ritualistically in heroic nudity wearing only a belt around its narrow waist. The Priest King’s complex asymmetrical posture encourages viewing from all sides. Overall the sculpture conveys a sense of alert, thoughtful, and assured majesty.

Figure of a Priest King (?) Sumerian, Uruk IV period, ca. 3300–3100 B.C. Copper alloy. Private collection

Foundation Figure of a Kneeling God Holding a Peg is an example of a well-preserved figurine of a god, recognizable as such by his headgear, topped by several pairs of bull horns. By firmly grasping the peg, the god is shown symbolically “nailing” the foundation of the temple forever to the earth. The sculptor has conveyed a naturalism and delicate fluidity in a figure fully realized in the round. Though immobilized by the permanence of the act itself, the muscular interaction of the body parts is well understood. The fine facial features as well as the deity’s erect posture convey a sense of divine certitude. The inscription on the peg is now too corroded to read, but, by analogy with earlier inscribed foundation figures, the deity probably represents the personal god of Gudea, ruler of Lagash.

Foundation Figure of a Kneeling God Holding a Peg. Second Dynasty of Lagash, reign of Gudea, ca. 2144–2124 B.C. Copper alloy. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchase, 1974

Foundation Figure in the Form of a Nail. Surmounted by the Bust of a God. Sumerian, Early Dynastic III period, ca. 2600–2300 B.C. Copper alloy. Private collection.

Foundation Figure in the Form of a Peg. Surmounted by the Bust of King Shulgi, Neo-Sumerian, Ur III period, reign of Shulgi, ca. 2094–2047 B.C. Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1959; 59.41.1.

Foundation Figure in the Form of a Peg. Surmounted by the Bust of King Ur-Namma, Neo-Sumerian, Ur III period, reign of Ur-Namma, ca. 2112–2094 B.C. Inscribed in Sumerian, To Inanna the lady of Eanna, his lady, Ur-Namma the mighty king, King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, her temple he built, to its place he restored it. Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. William H. Moore, 1947; 47.49.

Man Carrying a Box, Possibly for Offerings. Sumerian, Early Dynastic I–II period, ca. 2900–2600 B.C., Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1955; 55.142.

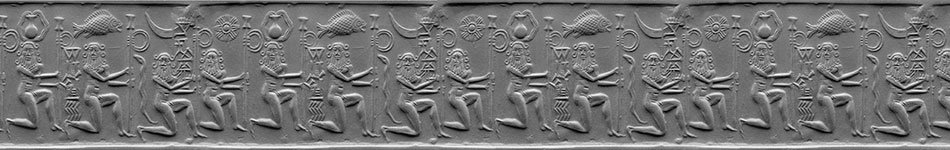

Priest King Feeding His Flock. Sumerian, Uruk IV period, ca. 3300–3100 B.C., Modern impression of a marble cylinder seal. Yale Babylonian Collection; NBC 2579.

Kneeling Nude Heroes Holding Gatepost Standards. Akkadian, ca. 2250–2150 B.C., Inscribed in Sumerian, Shatpum son of Shallum, Modern impression of a red jasper cylinder seal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lent by Jeannette and Jonathan P. Rosen; L.2011.55.2Akkadian, ca. 2250–2150 B.C., Inscribed in Sumerian, Shatpum son of Shallum, Modern impression of a red jasper cylinder seal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lent by Jeannette and Jonathan P. Rosen; L.2011.55.2

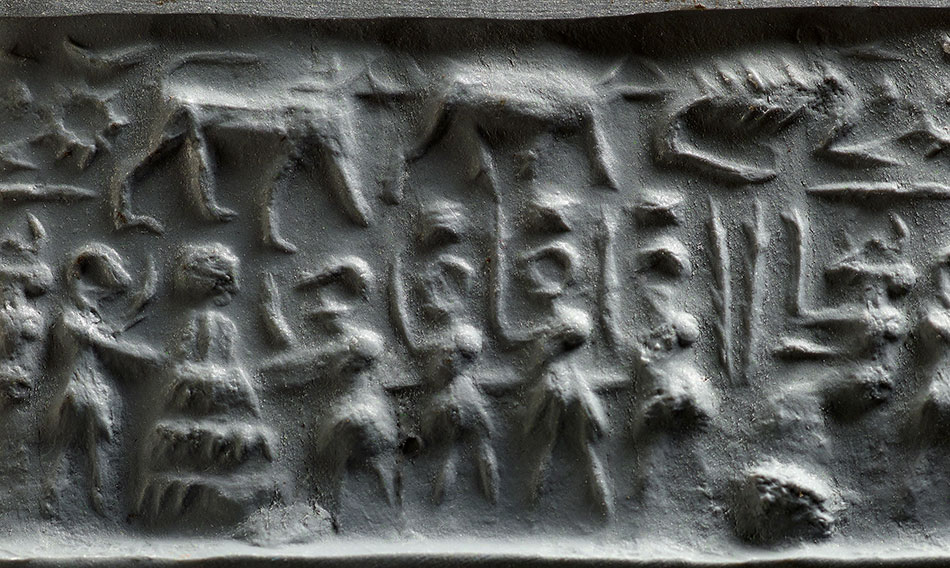

Detail Kneeling Nude Heroes Holding Gatepost Standards

Seated Goddess Before Figures Carrying Boxes on Their Heads. One Placed on an Altar, Sumerian, Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2600–2500 B.C, Modern impression of a marble cylinder seal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Martin and Sarah Cherkasky, 1984; 1984.383.5.

Kneeling Nude Heroes Holding Gatepost Standards. Akkadian, ca. 2250–2150 B.C., Inscribed in Sumerian, Shatpum son of Shallum, Cylinder seal, Red jasper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lent by Jeannette and. Jonathan P. Rosen; L.2011.55.2.

Kneeling Nude Heroes Holding Gatepost Standards. Akkadian, ca. 2250–2150 B.C., Inscribed in Sumerian, Shatpum son of Shallum, Cylinder seal, Red jasper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lent by Jeannette and. Jonathan P. Rosen; L.2011.55.2.

The Process of casting molten metal

How, why, and precisely when the process of casting molten metal to form representative images began is lost in the remotest past. However, it is clear that by 3300 B.C. in Ancient Mesopotamia, the cradle of Western civilization, the craft of casting metal had been perfected. By this time, the metal sculptor, through building a work from soft malleable wax, mastered the delicate fluidity of forms and their inherent naturalism, creating figures of striking originality.

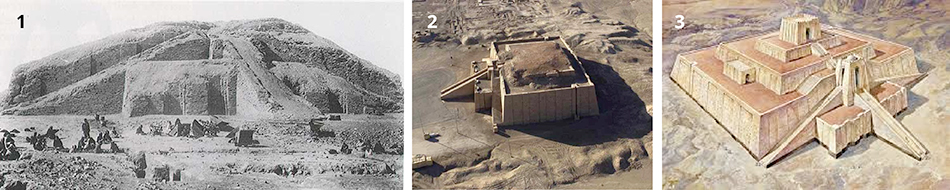

Temple of Enlil, Nippur, Southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq)

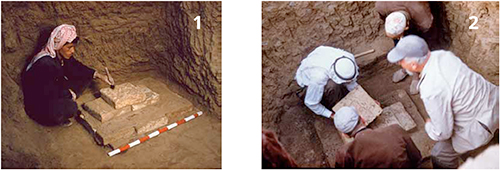

1 Remains of the Temple of Enlil, 1920 2 Temple partially restored, today 3 Reconstruction of the Temple

1 Intact foundation deposit, Temple of Enlil.

1 Intact foundation deposit, Temple of Enlil.

2 Removal of the first baked brick of the foundation deposit

During excavations carried out from 1955 to 1958, two foundation deposits each containing a figure of King Ur-Namma similar to the Morgan sculpture were found. The figures were placed deep in the earth under the lowest course of the structure in deposits made of baked brick and sealed with bitumen to make them air and water tight. The deposits were placed at the corner of a wall or under gate towers, probably marking the principal points of the temple’s plan, and were intended to record forever the pious works of royal builders. Upon rediscovery, they serve as a remarkable record of a period millennia removed from modern times.

Director’s Foreword

“Pierpont Morgan, the founder of the museum, was fascinated with the art and civilizations of the ancient world,” said Colin B. Bailey, director of the Morgan Library & Museum. “He made several trips to the Middle East and left the Morgan an extraordinary collection of cylinder seals and other artifacts that he had acquired. The exhibition Founding Figures continues this legacy and demonstrates the remarkable artistry of sculptors of the period who gave us figures of transcendent beauty.”

Free Brochure

A complimentary, fully-illustrated brochure will be available to visitors in the gallery, outlining all items on view in Founding Figures, including their provenance.

Organization and Sponsorship

The exhibition is organized by Sidney Babcock, Curator and Department Head, Ancient and Near Eastern Seals and Tablets at the Morgan Library & Museum.

Founding Figures Exhibition is made possible with generous support from Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen

Link

The Morgan Library & Museum