October 8 through December 3, 2017

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington

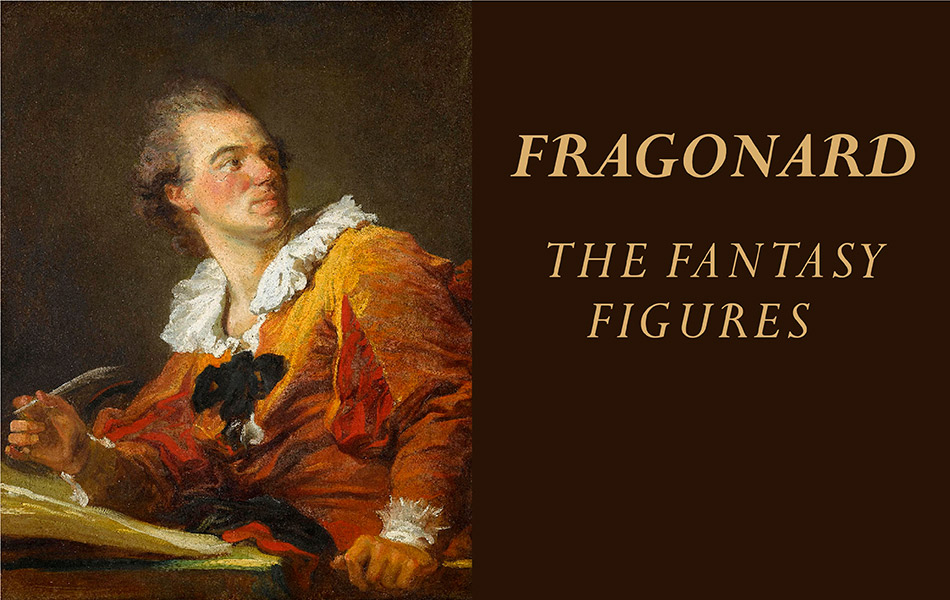

Fragonard: The Fantasy Figures, presents a series of rapidly masterfully executed, brightly colored paintings of lavishly costumed individuals.

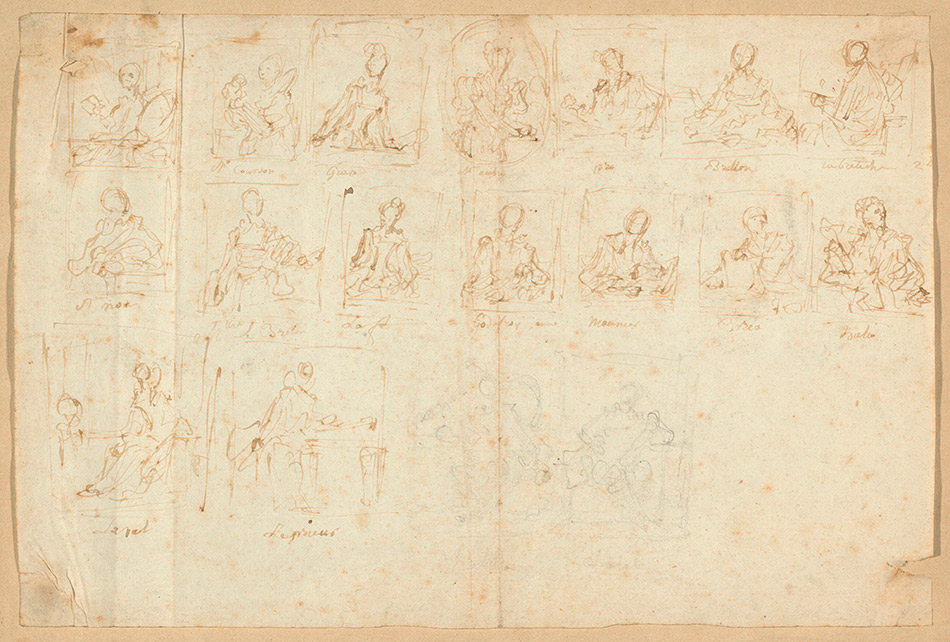

Covered with 18 thumbnail-sized sketches and apparently annotated in the rococo artist’s own hand, the drawing now known as Sketches of Portraits emerged at a Paris auction in 2012 and upended several long-held assumptions about the fantasy figures.

For the first time—a newly discovered drawing by Jean Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) and some 14 of his paintings that have been identified with it including the National Gallery of Art’s Young Girl Reading (c. 1769).

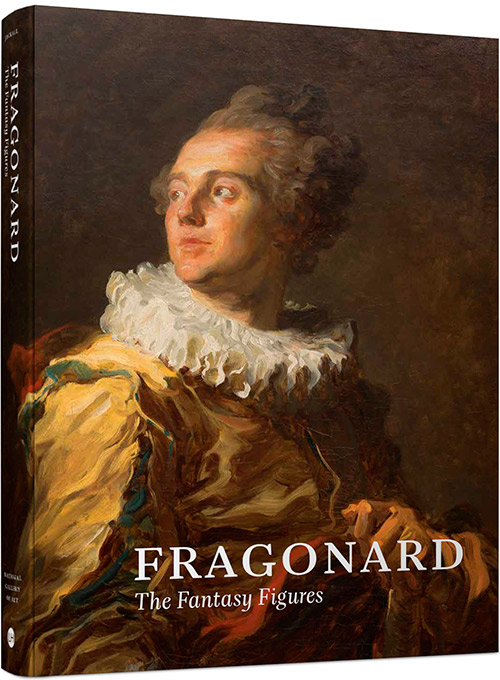

THE ACTOR

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Actor, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 81 x 65 cm (31 7/8 x 25 9/16 in.) framed: 106.68 x 89.54 cm (42 x 35 1/4 in.) Private Collection

Though traditionally titled The Actor, this portrait is thought to represent Gabriel Auguste Godefroy (1728–1813), the son of a wealthy Parisian banker, jeweler, and art dealer. Alternately a banker and naval officer, the younger Godefroy assembled a collection of paintings that included works by Fragonard.

Sketch of Portrait

Oil on canvas

M. DE LA BRETÈCHE

Jean Honoré Fragonard, M. de La Bretèche, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 80 x 65 cm (31 1/2 x 25 9/16 in.) framed: 112 x 87.5 cm (44 1/8 x 34 7/16 in.) Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Louis Richard de La Bretèche (1722–1804) was the receiver general of finance for the city of Tours and the older brother of the abbé de Saint-Non (no. 8), the subject of another fantasy figure. An old label on the back of the painting states that it portrays “Mr de La Breteche, / painted by Fragonard, / in 1769, in one hour’s time.”

Sketch of Portrait

Oil on canvas

PORTRAIT OF A MAN

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Portrait of a Man, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 85 x 65 cm (33 7/16 x 25 9/16 in.) framed: 113 x 90.5 cm (44 1/2 x 35 5/8 in.) Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

The inscription “Meunier” beneath the sketch was a startling discovery, as the corresponding painting had long been thought to portray the writer, art critic, and Enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot (1713–1784). The portrait of a man leaning against a book may represent instead the author and journalist Ange Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon (1702–1780).

Sketch of Portrait Oil on canvas

WOMAN WITH A DOG

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Woman with a Dog, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 81.3 x 65.4 cm (32 x 25 3/4 in.)

framed: 106.7 x 90.2 x 9.5 cm (42 x 35 1/2 x 3 3/4 in.) Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1937 (37.118) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image Source: Art Resource, NY

The inscription “Me Courson” (short for “Madame de Courson”) suggests that this portrait depictsMarie Émilie Coignet de Courson (1727–1806), who likely commissioned it. A wealthy aristocrat from a noble Burgundian family, she was a prominent figure on the Parisian social scene. Madame de Courson was also a close friend of another of Fragonard’s probable sitters, the countess Marie Anne Éléonore de Grave (1730–1807), whose portrait is represented on the drawing by the figure marked “Grave”.

Sketch of Portrait, Oil on canvas

THE VESTAL

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Vestal, c. 1769–1771, oil on canvas, overall: 80 x 63 cm (31 1/2 x 24 13/16 in.) with frame: 98 x 83 x 10 cm. Private Collection, courtesy Etienne Breton, Saint Honoré Art Consulting, Paris

This portrait presumably represents Catherine Thérèse Aubry (1733–1800), the widow of the president of the Bureau of Finances in the city of Tours. The woman’s white dress and veil, inspired by classical antiquity, prompted the portrait’s traditional title, The Vestal, which refers to the virginal priestesses of ancient Rome.

Sketch of Portrait Oil on canvas

THE WRITER

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Writer, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 80.5 x 64.5 cm (31 11/16 x 25 3/8 in.) framed: 115 x 91 cm (45 1/4 x 35 13/16 in.) Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Possibly this portrait of a man holding a quill pen represents the publisher Louis François Prault (pronounced “pro” in French; 1734–1807), seated at his desk, evidently at work on a manuscript.

Sketch of PortraitOil on canvas

THE WARRIOR

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Warrior, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 81.5 x 65.4 cm (32 1/16 x 25 3/4 in.) framed: 110.81 x 93.98 x 10.48 cm (43 5/8 x 37 x 4 1/8 in.) Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Image © Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA (photo by Michael Agee)

While similarities exist between the sketch and this painting, known as The Warrior, the inscription raises doubts about their association. The name “hale” or “hall” has been linked to Fragonard’s friend, the miniaturist Peter Adolphe Hall, who owned some twenty works by the artist, including a painting Hall described as a “head done after me from the time when [Fragonard] was doing portraits in one go.” However, other contemporary portraits indicate that Hall did not resemble the man represented in this portrait. The sketch may illustrate another, presumably lost, painting of a different sitter. Sketch of Portrait, Oil on canvas

THE SINGER

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Singer, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 81 x 65 cm (31 7/8 x 25 9/16 in.) Private Collection.

The woman depicted here holding a musical score has been associated with Anne Pauline Le Breton (1749–1821), a music lover who played the harpsichord. She apparently traveled in the same social circles as M. de La Bretèche and the abbé de Saint-Non.

Sketch of Portrait

Oil on canvas

CAVALIER SEATED BY A FOUNTAIN

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Cavalier Seated by a Fountain, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 94 x 74 cm (37 x 29 1/8 in.)

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, Bequest of Francesc Cambó, 1949

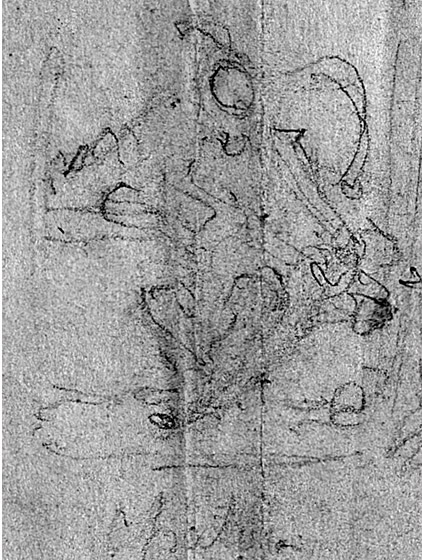

The sketch corresponding to Cavalier Seated by a Fountain is barely legible, as it was rendered in graphite rather than ink. The image below at left accentuates the drawn outlines. The sitter may be the financier Geoffroy Chalut de Vérin (1705–1787), who befriended Benjamin Franklin while the American statesman was in Paris to gain support for his country’s independence from Britain. The painting made its first public appearance at the 1777 Paris sale of the collection of Chalut de Vérin’s brother-in-law.

Processed infrared image of the sketch

FRANÇOIS-HENRI, DUC d’HARCOURT

Jean Honoré Fragonard, François-Henri, duc d’Harcourt, c. 1770, oil on canvas, overall: 81 x 65 cm (31 7/8 x 25 9/16 in.) Private Collection

Jean Honoré Fragonard, François-Henri, duc d’Harcourt, c. 1770, oil on canvas, overall: 81 x 65 cm (31 7/8 x 25 9/16 in.) Private Collection

PORTRAIT OF A MAN

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Portrait of a Man, c. 1775, oil on canvas, overall: 72 x 59.5 cm (28 3/8 x 23 7/16 in.) framed: 95.4 x 83.5 x 7.5 cm (37 9/16 x 32 7/8 x 2 15/16 in.) Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris © Petit Palais / Roger-Violet.

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Portrait of a Man, c. 1775, oil on canvas, overall: 72 x 59.5 cm (28 3/8 x 23 7/16 in.) framed: 95.4 x 83.5 x 7.5 cm (37 9/16 x 32 7/8 x 2 15/16 in.) Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris © Petit Palais / Roger-Violet.

MAN IN COSTUME

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Man in Costume, c. 1767-1768, oil on canvas, 80.3 x 64.7 cm (31 5/8 x 25 1/2 in.) The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mary and Leigh Block in honor of John Maxon, 1977.123. Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Man in Costume, c. 1767-1768, oil on canvas, 80.3 x 64.7 cm (31 5/8 x 25 1/2 in.) The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mary and Leigh Block in honor of John Maxon, 1977.123. Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago

ANNE-FRANÇOIS d’HARCOURT

DUC DE BEUVRON

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Anne-François d’Harcourt, duc de Beuvron, c. 1770, oil on canvas, overall: 81.5 x 65 cm (32 1/16 x 25 9/16 in.) Private Collection

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Anne-François d’Harcourt, duc de Beuvron, c. 1770, oil on canvas, overall: 81.5 x 65 cm (32 1/16 x 25 9/16 in.) Private Collection

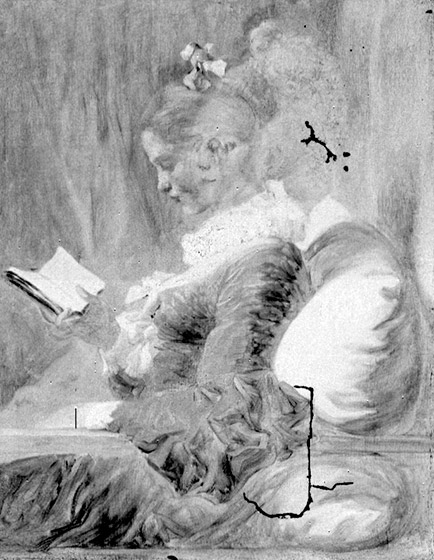

A Hidden Portrait Revealed

YOUNG GIRL READING

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Young Girl Reading, c. 1769, oil on canvas, overall: 81.1 x 64.8 cm (31 15/16 x 25 1/2 in.) framed: 104.9 x 89.5 x 2.2 cm (41 5/16 x 35 1/4 x 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Mellon Bruce in memory of her father, Andrew W. Mellon.

A question long posed of this painting has been, “Does it represent one of Fragonard’s fantasy figures?” Its dimensions, palette, and energetic brushwork conform to those of the known works in the group, as does the girl’s pseudo-Spanish costume with its elaborate ruff collar. Yet the other fantasy figures assume dramatic poses and turn their faces to meet the viewer’s gaze, whereas the girl in the Gallery’s painting is shown in quiet repose, turned in profile, enraptured by her book, oblivious to viewers. Recent technical studies and the discovery of the related drawing provide some answers.

Sketche of Portrait (detail)

Oil on canvas

In 2012–2013 a team of researchers at the Gallery used more sophisticated imaging techniques to gain a clearer view of the underlying portrait.

In 2012–2013 a team of researchers at the Gallery used more sophisticated imaging techniques to gain a clearer view of the underlying portrait.

This x-ray fluorescence (XRF) image reveals that it indeed depicted a woman. In addition, it became clear that this former figure wore a large feathered headdress.

The solid black lines indicate tears in the canvas that were repaired at an unknown date.

SKETCHES OF PORTRAITS

The Fantasy Figures Identified

Fragonard sketched many of his fantasy figures on this sheet. The drawing surfaced in Paris in 2012 and provided some answers to long-standing questions regarding the fantasy figures: Who are these people? Are they imaginary portraits? Or are they likenesses of real people? Beneath all but one sketch, Fragonard penned abbreviated names of the paintings’ sitters or patrons. These names appear to correspond to individuals from his circle of friends, acquaintances, and clients. Including members of the nobility, financiers, socialites, writers, singers, and fellow artists, they indicate the breadth of Fragonard’s social network.

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Sketches of Portraits, c. 1769, drawing unframed: 23 x 35 cm (9 1/16 x 13 3/4 in.) Private Collection, Paris

Jean Honoré Fragonard, Sketches of Portraits, c. 1769, drawing unframed: 23 x 35 cm (9 1/16 x 13 3/4 in.) Private Collection, Paris

ABOUT FRAGONARD

Text previously published in Philip Conisbee et al.,

“FRENCH PAINTINGS of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century”

The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue (Washington, DC, 2009), 149–150.

Fragonard was one of the most prolific of the eighteenth-century painters and draftsmen. Born in 1732 in Grasse in southern France, he moved with his family at an early age to Paris. He first took a position as a clerk, but having demonstrated an interest in art, he worked in the studio of the still life and genre painter Jean Siméon Chardin (French, 1699 – 1779). After spending a short time with Chardin, from whom he probably learned merely the bare rudiments of his craft, he entered the studio of François Boucher (French, 1703 – 1770).

Under Boucher’s tutelage Fragonard’s talent developed rapidly, and he was soon painting decorative pictures and pastoral subjects very close to his master’s style (for example, Diana and Endymion). Although Fragonard apparently never took courses at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, he entered the Prix de Rome competition in 1752, sponsored by Boucher, winning the coveted first prize on the strength of Jeroboam Sacrificing to the Idols (Paris, École des Beaux-Arts).

Under Boucher’s tutelage Fragonard’s talent developed rapidly, and he was soon painting decorative pictures and pastoral subjects very close to his master’s style (for example, Diana and Endymion). Although Fragonard apparently never took courses at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, he entered the Prix de Rome competition in 1752, sponsored by Boucher, winning the coveted first prize on the strength of Jeroboam Sacrificing to the Idols (Paris, École des Beaux-Arts).

Before leaving for Italy, however, he entered the École des élèves protégés in Paris, a school established to train the most promising students of the Académie royale.

Before leaving for Italy, however, he entered the École des élèves protégés in Paris, a school established to train the most promising students of the Académie royale.

There he studied history and the classics and worked with the director, Carle Van Loo (French, 1705 – 1765), one of the leading painters of the day. Van Loo’s influence on Fragonard’s art is evident in the large Psyche Showing Her Sisters the Gifts She Has Received from Cupid (London, National Gallery), a fluidly painted work that was exhibited to King Louis XV (r. 1715–1774) in 1754.

Following his stint at the École, Fragonard traveled to Italy, spending the years 1756–1761 at the Académie de France in Rome. Fragonard’s slow progress (or his unwillingness to complete his assigned artistic chores) concerned the director, Charles Joseph Natoire (French, 1700 – 1777), but the young artist showed greater promise when he was steered toward sketching in the open air, a practice that Natoire encouraged. Inspired by such landscapists active in Italy as Hubert Robert (French, 1733 – 1808) and Claude-Joseph Vernet (French, 1714 – 1789) and by the patronage of the Abbé de Saint-Non (1727–1791), an accomplished amateur and avid collector, Fragonard developed an interest in landscape painting and drawing that would remain an important aspect of his art throughout his life. During the summer of 1760, spent with Saint-Non at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, Fragonard produced a series of red chalk drawings of the gardens and principal sites of the town that are among the greatest examples of landscape art of the century. He returned to France in the company of Saint-Non, with whom he had traveled extensively through Italy, making drawings of the principal architectural sites and works of art that they encountered. Saint-Non later used these drawings as the basis for a series of etchings and aquatints. (fragonards-enterprise-the-artist-and-the-literature-of-travel)

Back in Paris, Fragonard painted small cabinet pictures—primarily landscapes and genre scenes—for the art market and a growing group of admirers. He made his public debut at the Salon of 1765 with the stunning Corésus and Callirhoé (Paris, Musée du Louvre), a monumental canvas that seemed to herald his arrival as the most promising history painter of his generation. The grand machine won him probationary acceptance into the Académie and the accolades of the critic Denis Diderot (French, 1713 – 1784), who discussed the picture at length in his Salon review in the Correspondance littéraire.

Back in Paris, Fragonard painted small cabinet pictures—primarily landscapes and genre scenes—for the art market and a growing group of admirers. He made his public debut at the Salon of 1765 with the stunning Corésus and Callirhoé (Paris, Musée du Louvre), a monumental canvas that seemed to herald his arrival as the most promising history painter of his generation. The grand machine won him probationary acceptance into the Académie and the accolades of the critic Denis Diderot (French, 1713 – 1784), who discussed the picture at length in his Salon review in the Correspondance littéraire.

Despite this early success, Fragonard declined to pursue a public career as a history painter, preferring to work for a private clientele of financiers and courtiers. The failure of the crown to reimburse him promptly for the Corésus may have been a factor in his decision. As a result, little documentation and critical commentary concerning Fragonard’s art survives, and only recently has the development of his career, his patrons, and the significance of his innovative imagery begun to be fully explored, notably in the exhibition held in Paris and New York in 1987–1988.

Nevertheless, Fragonard is rightly considered among the most characteristic and important French painters of the second half of the eighteenth century. Over four decades, he produced many brilliantly realized easel paintings, such as The Swing (London, Wallace Collection), commissioned in 1767, or the Portraits de fantaisie (Paris, Musée du Louvre, and elsewhere), painted in the late 1760s and early 1770s; and large-scale decorative works, the most significant extant example being the four magisterial canvases known as the Progress of Love (1771–1772; New York, Frick Collection), commissioned by Madame du Barry (1743–1793) for her country retreat at Louveciennes.

Nevertheless, Fragonard is rightly considered among the most characteristic and important French painters of the second half of the eighteenth century. Over four decades, he produced many brilliantly realized easel paintings, such as The Swing (London, Wallace Collection), commissioned in 1767, or the Portraits de fantaisie (Paris, Musée du Louvre, and elsewhere), painted in the late 1760s and early 1770s; and large-scale decorative works, the most significant extant example being the four magisterial canvases known as the Progress of Love (1771–1772; New York, Frick Collection), commissioned by Madame du Barry (1743–1793) for her country retreat at Louveciennes.

These paintings marked Fragonard as among the most innovative and brilliant painters of the day, yet his apparently whimsical temperament and independent ways meant that he never realized the conventional rewards his talent deserved. The Louveciennes paintings were returned to the artist, replaced by drier yet more currently neoclassical compositions by Joseph Marie Vien (1716–1809) (Paris, Musée du Louvre, and Paris, Château de Chambéry), and other commissions were left incomplete. Yet Fragonard earned a good living selling paintings to a close-knit group of collectors, many of them drawn from the ranks of the fermiers généraux (tax farmers), and by providing brilliant wash drawings as illustrations for various luxurious book publishing projects.

A second trip to Italy in 1773–1774 in the company of the financier Pierre Jacques Onésyme Bergeret de Grancourt (1715–1785), one of the artist’s major patrons, rekindled Fragonard’s interest in landscape and garden imagery, leading to such masterpieces as the Fête at Saint-Cloud (Paris, Banque de France) and the pendants Blindman’s Buff and The Swing (NGA), datable to the late 1770s. During these years Fragonard also produced numerous ink and wash drawings whose broad handling and vivid luminosity reflect an ever-increasing self-assurance and technical command. Always a changeable artist, he simultaneously painted tightly wrought cabinet pictures in an erotic vein, the most celebrated example being The Bolt (c. 1777–1778; Paris, Musée du Louvre), made popular through engravings. Such late works—highly finished pictures focusing on intimate themes—show a fascination with the goût hollandais, an influence he passed on to his only true student, his sister-in-law Marguerite Gérard (French, 1761 – 1837), with whom he sometimes collaborated.

A second trip to Italy in 1773–1774 in the company of the financier Pierre Jacques Onésyme Bergeret de Grancourt (1715–1785), one of the artist’s major patrons, rekindled Fragonard’s interest in landscape and garden imagery, leading to such masterpieces as the Fête at Saint-Cloud (Paris, Banque de France) and the pendants Blindman’s Buff and The Swing (NGA), datable to the late 1770s. During these years Fragonard also produced numerous ink and wash drawings whose broad handling and vivid luminosity reflect an ever-increasing self-assurance and technical command. Always a changeable artist, he simultaneously painted tightly wrought cabinet pictures in an erotic vein, the most celebrated example being The Bolt (c. 1777–1778; Paris, Musée du Louvre), made popular through engravings. Such late works—highly finished pictures focusing on intimate themes—show a fascination with the goût hollandais, an influence he passed on to his only true student, his sister-in-law Marguerite Gérard (French, 1761 – 1837), with whom he sometimes collaborated.

Certain of Fragonard’s later paintings, like The Invocation to Love, known in numerous versions, also demonstrate a darker, more emotional character that anticipates romanticism. During the revolution Fragonard left Paris for his native Grasse, taking with him The Progress of Love cycle, which he reassembled in the house of his cousin. In 1793 he returned to Paris, where his old acquaintance Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 – 1825) appointed him a curator at the new national museum. During the last decade of his life his artistic production lessened, perhaps in the recognition that his late rococo style was out of step with the times. He died in 1806.

Certain of Fragonard’s later paintings, like The Invocation to Love, known in numerous versions, also demonstrate a darker, more emotional character that anticipates romanticism. During the revolution Fragonard left Paris for his native Grasse, taking with him The Progress of Love cycle, which he reassembled in the house of his cousin. In 1793 he returned to Paris, where his old acquaintance Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 – 1825) appointed him a curator at the new national museum. During the last decade of his life his artistic production lessened, perhaps in the recognition that his late rococo style was out of step with the times. He died in 1806.

Richard Rand

January 1, 2009

STATEMENT

STATEMENT

Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art, Washington

“The first exhibition to unite the fantasy figures with the recently discovered drawing focuses on this aspect of Fragonard’s production in a powerful and intimate way,”

“We are grateful to the public and private collections, both here and abroad, that have generously lent to this exhibition, as well as to Lionel and Ariane Sauvage whose gift supported the catalog’s publication.”

Exhibition Curator. The exhibition is curated by Yuriko Jackall, assistant curator, department of French paintings, National Gallery of Art.

Organization and Support. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

CATALOGUE

Edited by Yuriko Jackall, with essays by Carole Blumenfeld, Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, Jean-Pierre Cuzin, John Delaney, Elodie Kong, Satish Padiyar, and Michael Swicklik

Hardcover

8 x 11 inches

160 pages, 190 color illustrations

Published: 2017

$49.99

Accompanying the National Gallery of Art exhibition Fragonard: The Fantasy Figures, this catalog constitutes an important compendium of new information and visual material on Fragonard’s much-studied series. Combining art, fashion, science, and conservation, this revelatory exhibition brings together—for the first time—14 of Fragonard’s known fantasy-figure paintings.

The book assembles Fragonard’s fantasy figures alongside his original sketches for the first time. It presents scientific research into the mysterious series and examines the 18th-century Parisian world of new money, unexpected social alliances, and extravagant fashions from which these unique paintings emerged.

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington

6th and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20565

Telephone: (202) 737-4215 Accessibility Information: (202) 842-6905

http://www.nga.gov/

Hours: Monday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Sunday, 11 a.m.–6 p.m.