INSTRUCTION AND DELIGHT

YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART

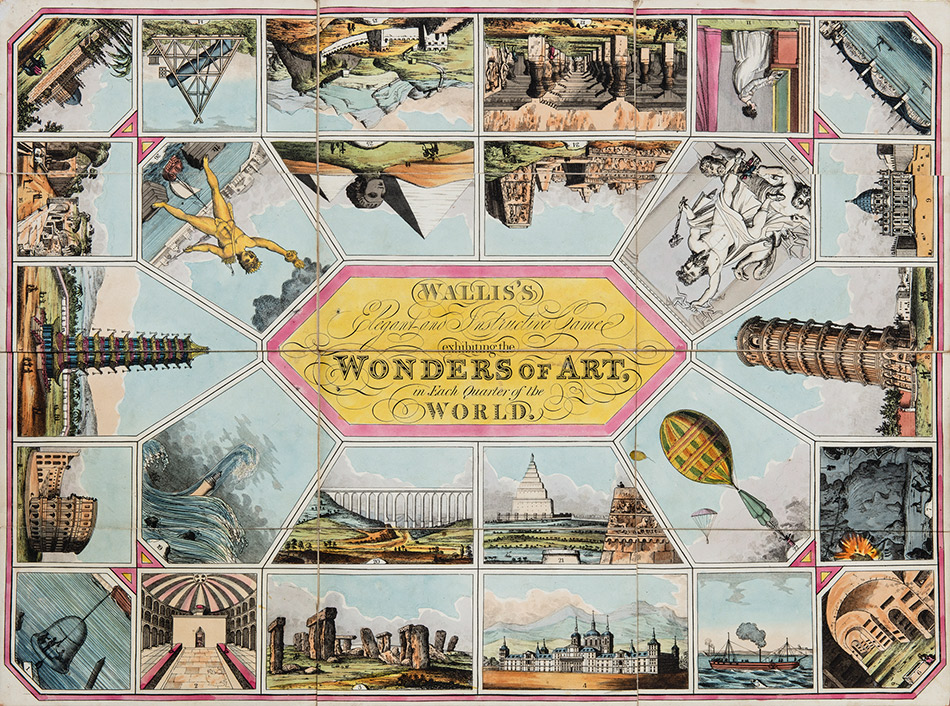

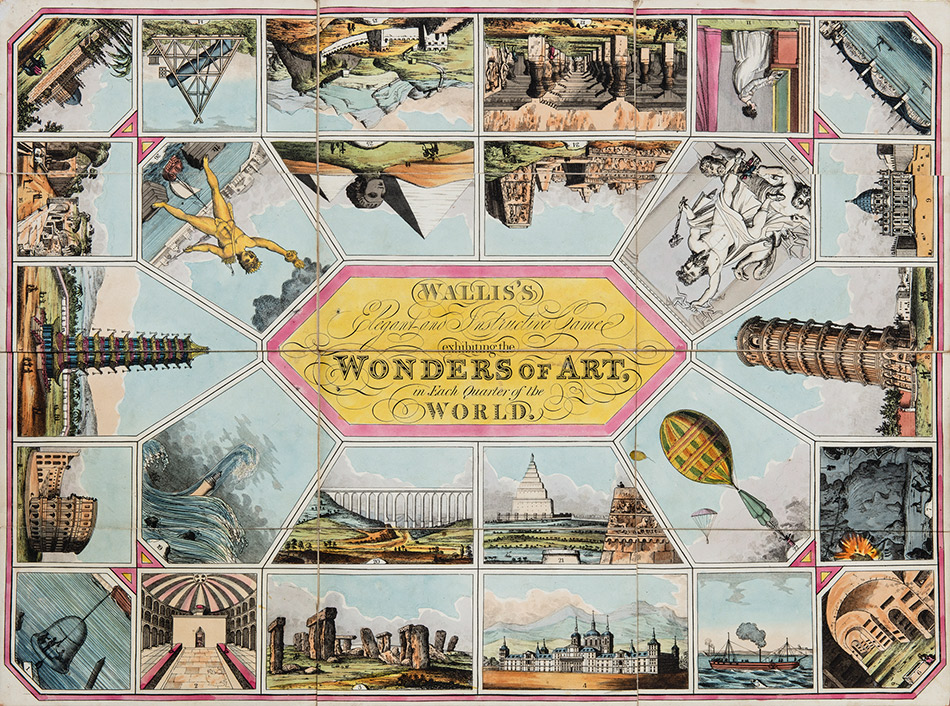

Wallis’s Elegant and Instructive Game Exhibiting the Wonders of Art, in Each Quarter of the World,

London: Edward Wallis, ca.1820, 64 x 47 cm.

The Philosopher of a New Approach to Children’s Education

The Philosopher of a New Approach to Children’s Education

By the turn of the eighteenth century in Britain, parents and teachers had begun to embrace wholeheartedly a suggestion from the philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) that “Learning might be made a Play and Recreation to Children.” IMAGE: John Locke portrait

The Father of Children’s Literature

The Father of Children’s Literature

British publishers leapt at the chance to supply books and games for “instruction with delight,” as John Newbery put it in A Little Pretty Pocket-book (1744), one of the first children’s books ever published. IMAGES: John Newbery portrait and his first children’s book

The purpose of these games

Games were designed for educational reasons—to teach history, geography, arithmetic, and science—or simply for pure entertainment (or a strategic combination of the two). Certain ones were intended explicitly to instill proper behavior in real life by presenting choices and their consequences in play, improving minds and morals. Other games served as templates for imaginative play, allowing children (and the adults who played alongside) to be armchair travelers and learn about the world from the comforts of home.

THE GAMES

An Arithmetical Pastime; Intended to Infuse the Rudiments of Arithmetic; Under the Idea of Amusement, London: John Wallis, 1798, 36 x 32 cm.

An Arithmetical Pastime; Intended to Infuse the Rudiments of Arithmetic; Under the Idea of Amusement, London: John Wallis, 1798, 36 x 32 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Players learned arithmetic from the tables printed in the corners of this board and from the charts beneath the rules. The rhymes that correspond to the numbered circles provided additional moral lessons.

The Circle of Knowledge, a New Game of the Wonders of Nature, Science & Art, London: John Passmore, ca. 1850, 51 x 65 cm.

The Circle of Knowledge, a New Game of the Wonders of Nature, Science & Art, London: John Passmore, ca. 1850, 51 x 65 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: The rings of the game are named for the continents, the seasons, the four elements (air, fire, earth, water), and for chemistry, optics, astronomy, and electricity. A player needed to answer questions hat correspond to the numbered spaces in order to end up in the Circle of Knowledge in the center.

Crowned Heads, or, Contemporary Sovereigns, An Instructive Game, London: David Ogilvy, ca. 1845, 76 x 56 cm.

Crowned Heads, or, Contemporary Sovereigns, An Instructive Game, London: David Ogilvy, ca. 1845, 76 x 56 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: In this game, players had to identify the reigning monarchs and major events of the countries that are pictured on the map.

The Royal Pastime of Cupid, or Entertaining Game of the Snake, London: Robert Laurie and James Whittle, 1794, 46 x 38 cm.

The Royal Pastime of Cupid, or Entertaining Game of the Snake, London: Robert Laurie and James Whittle, 1794, 46 x 38 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This is the oldest board game in the Liman collection. The object of the game was for the player to move through the snake’s serpentine course to reach the Garden of Cupid at the end. Along the way were multiple hazards, with forfeits that included losing a turn, moving back a number of spaces, or giving up counters to the pool. The most dangerous square was the Coffin (square 59), sending the player back to the start.

Laurie’s New and Entertaining Game of the Golden Goose, London: Richard Holmes Laurie, 1831, 40 x 51 cm.

Laurie’s New and Entertaining Game of the Golden Goose, London: Richard Holmes Laurie, 1831, 40 x 51 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Like The Royal Pastime of Cupid, or, Entertaining Game of the Snake (at left), this game is a classic race game, with the track laid within an outline of a goose. Players lost a turn if they landed on the Inn, as payment for “beverages.” Death (square 58) was the worst roll; those who landed on it had to go back to the start.

The Hare and the Tortoise: A New Game, London: William Spooner, 1849, with wood box with sliding lid and paper label, game: 52 x 44 cm., box: 5 x 5.5 x 7.5 cm.

The Hare and the Tortoise: A New Game, London: William Spooner, 1849, with wood box with sliding lid and paper label, game: 52 x 44 cm., box: 5 x 5.5 x 7.5 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: In this race game, the track starts at the hare’s rear left foot and winds about between its back legs until space 8. Space 9 then appears on the tortoise, but the numbering reverts to the hare with space 10. This apparent confusion was done on purpose, for as the instructions direct, any player “who carries his mark to a wrong number must pay 2 [counters] to the pool.” The wood box designed to hold the counters for this game may be seen in the case below, with the cover to the game.

The Mansion of Bliss: A New Game for the Amusement of Youth, London: William Darton, 1822, 57 x 46 cm.

The Mansion of Bliss: A New Game for the Amusement of Youth, London: William Darton, 1822, 57 x 46 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Each numbered square has a corresponding moralizing rhyme for the players to read (in the accompanying booklet, not on view), with rewards and penalties noted. Players who land on square 20, for example, are Truants and must lose their turn twice: “The truant to School must return, / For such negligence cannot be look’d o’er; / And stay while each player turns twice, / Then, perhaps, he’ll be guilty no more.” The winner was the first player to reach the Mansion of Bliss at the center of the board.

The Mirror of Truth, London: William Spooner, 1848, 56 x 44 cm.

The Mirror of Truth, London: William Spooner, 1848, 56 x 44 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This moralizing game attempted to teach children how to live a virtuous life despite the attraction of a full range of vices (including, but not limited to, intemperance, idleness, selfishness, lying, envy, hypocrisy, passion, and pride). The author of the accompanying booklet (not on view) notes that “the chief object . . . has been to combine information with amusement, and present to youth a means of employing those hours in a rational and delightful manner”—hours “usually devoted to the pernicious science of [playing] cards.” Players read stories associated with each numbered square, “selected from the Pages of History, unembellished by the hand of Fiction,” providing “examples for imitation; whither they will perceive the path of virtue can alone conduct them,” that would lead them eventually to the Temple of Happiness at the center.

The Paths of Life, London: J.H. Cotterell, 1840, 64 x 61 cm.

The Paths of Life, London: J.H. Cotterell, 1840, 64 x 61 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Although at first glance this board looks like a simple geographic game, its actual intent was to send a moralizing message about the consequences of choosing certain paths in life. Starting from Parental Care Hall at the top (1), players spun the teetotum and if the result was a one or two, they began their life on the “bad” road, moving through Careless Backway (2), into Careless County, passing by attractions such as Cock-Match Pit (15), and ending up in a Drunkard’s Hovel (26) or Gaming Quicksands (25) in the Poverty Maze.

On the other hand, players who got a three or four at the start could proceed on the “good” road, traveling through Direction Gate (2) and Discreet County, and stopping at Good Book Pastures (6), Many Friends City (13), or Comfort Cottage (29).

There were occasional opportunities to change your destiny—if you were lucky enough to land on the numbered circles in black (such as Risk Lane or Knave’s Lure) you were offered a road “either into a good or bad Route”—but on the whole, it was a straight path to the bottom of the board: either to the Bottomless Pit (36) and losing the game, or to Happy Old Age Hall (37) and winning it all.

The Royal Regatta: A Game, London: David Ogilvy, ca. 1852, 74 x 55 cm.

The Royal Regatta: A Game, London: David Ogilvy, ca. 1852, 74 x 55 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This game depicts a yacht race around the Isle of Wight, with the Royal Navy fleet and the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert in attendance, and a fashionably dressed crowd watching from above Portsmouth Harbour. It was published to commemorate the Royal Yacht Squadron’s Hundred Guinea Cup regatta of August 1851, in which fifteen yachts raced clockwise around the Isle of Wight. The race was won by the schooner America, and the trophy was renamed the America’s Cup. Considered the oldest international sporting trophy, it is currently held by the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron, who will stage the thirty-sixth defense of the Cup in 2021.

Science in Sport, or, The Pleasures of Astronomy: A New Instructive Pastime, London: Edward Wallis, 1804, 57 x 44 cm. HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Margaret Bryan (fl. 1795–1816) ran a girl’s school in Blackheath, London, and was the author of a number of popular works on science. The publisher Edward Wallis likely felt that her association with this game would be a testament to its accuracy, as well as highlight its suitability for both boys and girls. The board has thirty-five numbered squares depicting astronomical objects, instruments, and principles, as well as portraits of astronomers (Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, Nicholas Copernicus, and Isaac Newton). The center panel depicts the Royal Observatory (Flamsteed House) in Greenwich, England, from which the prime meridian is defined.

Science in Sport, or, The Pleasures of Astronomy: A New Instructive Pastime, London: Edward Wallis, 1804, 57 x 44 cm. HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Margaret Bryan (fl. 1795–1816) ran a girl’s school in Blackheath, London, and was the author of a number of popular works on science. The publisher Edward Wallis likely felt that her association with this game would be a testament to its accuracy, as well as highlight its suitability for both boys and girls. The board has thirty-five numbered squares depicting astronomical objects, instruments, and principles, as well as portraits of astronomers (Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, Nicholas Copernicus, and Isaac Newton). The center panel depicts the Royal Observatory (Flamsteed House) in Greenwich, England, from which the prime meridian is defined.

The first player who landed there could assume the title of Astronomer Royal, but there were hazards along the way. Landing on square 15, for example, with its depiction of the The Man in the Moon—“the ridiculous idea of some ignorant people”—would send the player back to square 13, to read about The Phases of the Moon, so “that [he or she] may know better.”

Wallis’s Tour of Europe, A New Geographical Pastime, London: John Wallis, 1794, 71 x 49 cm.

Wallis’s Tour of Europe, A New Geographical Pastime, London: John Wallis, 1794, 71 x 49 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This geographic game includes stops for all the cities someone might visit while on a tour of Europe. The game begins in Harwich (1), a major port on the eastern coast of England where many tourists would take a packet boat to the continent.

Players of Wallis’s game would spin a teetotum (also called a “totum” as here) to move their markers along the route, occasionally losing a turn or two to learn about some local attraction on their way back to London (102), the last stop. Or, if they were lucky enough to land on Paris (49), for example, players were “entitled to view all its curiosities” and skip ahead, all the way to Dublin (99). Close to home, the most dangerous stop was the Scilly Isles (89, just off the coast of Cornwall in southwest England), where, “by running foul of the rocks, the Traveller loses the game.”

The Magic Ring: A New Game, Replete with Humour and Pleasant Variety, London: Champante and Whitrow, 1796. With slipcase.

The Magic Ring: A New Game, Replete with Humour and Pleasant Variety, London: Champante and Whitrow, 1796. With slipcase.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This game “may be played by any number of persons, from two or three or up to eighteen, or more.” Players encountered multiple hazards as they raced toward the Magic Ring in the center. Landing on The Overturned Waggon (10), for example, could cause quite a delay: “he that meets with this accident, must stay till the broken wheel is mended, which happens as soon as he spins the same number in his two-goes [two turns].” Meeting the Old Scold’s “abusive tongue” (22) would send the player back to space number 18, while the person who landed on The Book (35) “must sit down and study till another come to take it from him, or till he spins an even number in some of his subsequent goes.”

The slipcase notes that the game is accompanied by a box with a teetotum (used for determining the player’s moves) and counters. While the original wood box and its contents is now lost, it was likely similar to the one on display here.

The Wonders of the World, London: William Spooner, with instruction booklet, ca. 1843, 43 x 54 cm.

The Wonders of the World, London: William Spooner, with instruction booklet, ca. 1843, 43 x 54 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This board depicts examples of ancient, classical, and more recent architectural sites, including Petra, Alhambra, Leaning Tower of Pisa, St. Peter’s in Rome, and St. Paul’s in London. Printed purposely without numbered spaces, the game forced a player to study the text of the accompanying booklet before a move could be made, for “in so doing, his memory will become impressed with the name and character of the object he has to seek.” The first player to land on the image of the Parthenon—at the top of the board—would win the game.

Fortunio & His Seven Gifted Servants, London: William Spooner, 1846, with instruction sheet, 43 x 56 cm.

Fortunio & His Seven Gifted Servants, London: William Spooner, 1846, with instruction sheet, 43 x 56 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This game is based on a popular play, Fortunio and His Seven Gifted Servants: A Fairy Extravaganza, in Two Acts, by J. R. Planché, first produced at Drury Lane Theatre, London, in 1843. Players are led through the narrative of the drama, earning rewards or paying forfeits, until the winner reaches the center image, The Court of the Emperor Matapa. The accompanying folded sheet provides the rules as well as a synopsis of the play. Comic Game of the Great Exhibition of 1851. London: William Spooner, 1851, hand-colored lithograph, with printed “prize” tickets and markers, in wood box. Gift of Ellen and Arthur Liman, Yale JD 1957.

The New Game of Multiplication Table, London: D. Carvalho, ca. 1830–32, with slipcase, 48 x 38 cm.

The New Game of Multiplication Table, London: D. Carvalho, ca. 1830–32, with slipcase, 48 x 38 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: The players advanced through the game as they mastered the multiplication tables.

The Majestic Game of the Asiatic Ostrich. London: William Darton, 1822. 51 x 41 cm., with slipcase.

The Majestic Game of the Asiatic Ostrich. London: William Darton, 1822. 51 x 41 cm., with slipcase.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: The purpose of this game was to offer lessons about the hierarchy of the British peerage, the clergy, and the military. It was likely published to commemorate the recent coronation of George IV, depicted in the winning square at the center (20).

Spooner’s Pictorial Map of England & Wales, London: William Spooner, 1844, 52 x 62 cm.

Spooner’s Pictorial Map of England & Wales, London: William Spooner, 1844, 52 x 62 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This map game includes vignettes of sites of interest in England and Wales; the route begins in Berwick-upon-Tweed (1), the northernmost town in England, and ends in London (104).

Why, What, & Because: or, The Road to the Temple of Knowledge, London: William Sallis, ca. 1855, with instruction booklet, 46 x 33 cm.

Why, What, & Because: or, The Road to the Temple of Knowledge, London: William Sallis, ca. 1855, with instruction booklet, 46 x 33 cm.

HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: Correct answers to simple questions posed in the accompanying booklet (such as “What is lightening?” Answer: “Lightning is accumulated Electricty [sic] discharged from the Clouds”) allowed the players to advance, ending with the crowning of two successful pupils in the Temple of Knowledge (78).

Wallis’s Elegant and Instructive Game Exhibiting the Wonders of Art, in Each Quarter of the World, London: Edward Wallis, ca.1820, 64 x 47 cm. HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This game board features vignettes illustrating a curious mix of ancient sites, such as Stone Henge (3) and the Walls of Babylon (21), with more contemporary attractions and inventions, including the Automaton at Spring Gardens (11), “a Musical Lady, who performs delightfully upon the piano”; and Doctor Herschel’s Telescope (14), referring to William Herschel’s forty-foot reflecting telescope, constructed between 1785 and 1789. The first player to reach the center of the board won the game.

Wallis’s Elegant and Instructive Game Exhibiting the Wonders of Art, in Each Quarter of the World, London: Edward Wallis, ca.1820, 64 x 47 cm. HOW TO PLAY THE GAME: This game board features vignettes illustrating a curious mix of ancient sites, such as Stone Henge (3) and the Walls of Babylon (21), with more contemporary attractions and inventions, including the Automaton at Spring Gardens (11), “a Musical Lady, who performs delightfully upon the piano”; and Doctor Herschel’s Telescope (14), referring to William Herschel’s forty-foot reflecting telescope, constructed between 1785 and 1789. The first player to reach the center of the board won the game.

Thanks to collectors Ellen and Arthur Liman

Despite the best efforts of the makers—like mounting fragile paper on sturdy linen that could be folded and stored in a slipcase—many of the board games fell apart due to enthusiastic use, while instructions were easily lost, making it difficult to determine how children of an earlier age may have engaged with them. Fortunately, the Liman games are intact, with their slipcases and directions present, helping us to reconstruct the experiences of the original owners.

Despite the best efforts of the makers—like mounting fragile paper on sturdy linen that could be folded and stored in a slipcase—many of the board games fell apart due to enthusiastic use, while instructions were easily lost, making it difficult to determine how children of an earlier age may have engaged with them. Fortunately, the Liman games are intact, with their slipcases and directions present, helping us to reconstruct the experiences of the original owners.

The collection allows us to follow the course of the Industrial Revolution and the expansion of the British Empire in conjunction with changing attitudes toward childhood and education.

And, put quite simply, in the words of Ellen Liman, “the games we so lovingly and assiduously collected [over decades] are now preserved . . . for you to enjoy as much as we have.”

IMAGE: Attorney Arthur Liman and wife Ellen, 1993

CURATORS:

Instruction and Delight: Children’s Games from the Ellen and Arthur Liman Collection has been curated by Elisabeth Fairman, Chief Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Yale Center for British Art, with the assistance of Laura Callery, Senior Curatorial Assistant.

YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART

1080 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut

Toll free: 1 877 BRIT ART (274 8278) (within the United States)

International: +1 203 432 2800