Five centuries of Japanese painting. The Perino Collection

Five centuries of Japanese painting. The Perino Collection

MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Turin

November 12, 2021 – April 25, 2022

![]()

Marco Guglielminotti Trivel

East Asia Curator, MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Turin

“The hanging scrolls characterise the pictorial production of China, Korea and Vietnam, as well as Japan itself, and with some variations in the support, are the equivalent of framed Western paintings”. “Unlike our canvases or panels, rigid structures built to be hung on a wall for an extended period, the painted scrolls are designed for use over limited time and have a relatively soft structure”.

“Hung in the tokonoma (alcove) of the Japanese home, or mounted for just a few hours in a garden, fluttering in the breeze, these works of art participate in time and movement, whereas Western paintings seem imbued with fixity and continuity. Differences are not purely formal, as they reflect a different aesthetic and philosophical conception: kakemono are an allusion to impermanence and change as inescapable (and positive) aspects of existence”.

Francesco Paolo Campione

Francesco Paolo Campione

Director, Museo delle Culture, Lugano

“Kakemono is a project born with a clear aim: to recount five centuries of Japanese painting, accompanying the public – regardless of the different levels of interpretation – in an exciting journey of forms and subjects; a journey capable of conveying the distinctiveness not only of Japanese painting but, more broadly, of visual representation in Japanese civilisation”.

Exhibition Curated by the Dutch scholar Matthi Forrer, an oriental art historian and expert in Japanese painting, also has written the texts of the works that appear in this article and those of the extensive catalog published by SKIRA that reproduces the 125 works presented in the exhibition.

Kakemono exhibition is set up in five thematic sections

Flowers and Birds, Animals, Figures,

Landscapes, Plants and Flowers

The exhibition presents an exuberant world with meticulous and naturalistic representations, enriched by subtle details, where form loses its contours to become an enchanting and evocative sign, in an extreme exercise of synthesis and refinement, almost an abstractionism.

Comment by Matthi Forrer

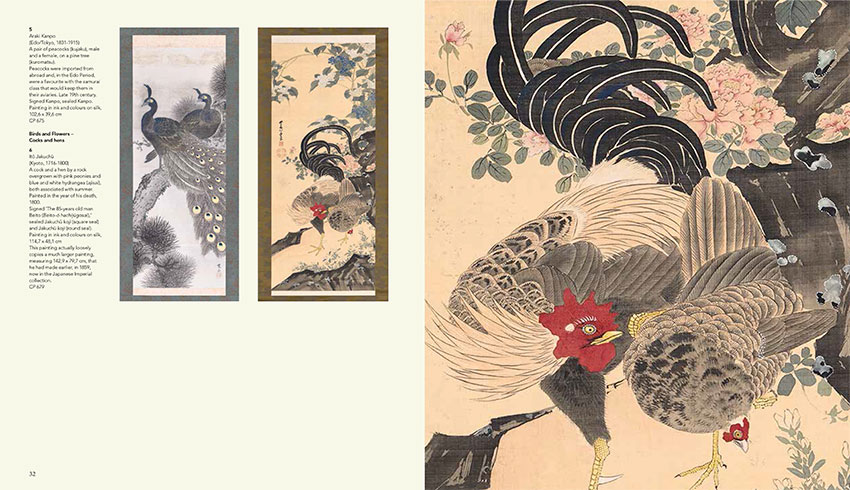

“From early on, kacho¯ -ga, ‘paintings of birds and flowers,’ are one of the major genres in the Chinese and Japanese painting traditions. Some birds have one or two flowers, plants, or trees to be commonly associated with, such as pheasants with peonies growing on rocks. It is believed that pheasants are unhappy without a mate, and so are emblematic of conjugal happiness”.

“Also a rooster and a hen, preferably with chicks,

are suggestive of a happy family”

Ch¯o Gessh¯o (Kyoto, Nagoya, 1772-1832) A rooster and hen by a red flowering amaranth (hageit ¯o). The rooster is walking down a slope, whereas the hen is taking care of a young chick. The most likely association is with a happy family. 1820s. Signed Gessh¯o, sealed Shinz ¯o/ Gessh¯o. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 98,1 x 37,3 cm. CP 312

“Mandarin ducks are a symbol of conjugal fidelity and,

indeed, they are invariably found in pairs in paintings”

Komai Ki, also known as Genki (Kyoto, 1747-1797) A couple of mandarin ducks (oshidori), the male on the stem of a snow-laden plum (ume), the female seen half-hidden underneath. The few open pink plum blossoms suggest the New Year rather than just winter, as well as conjugal fidelity as the most obvious symbolism of mandarin ducks. 1780s-90s. Signed Genki, sealed Genki/Shion. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 113,8 x 41,6 cm. CP 605

“Otherwise, quite a few birds are associated with specific seasons,

sometimes even with specific months”

Watanabe Seitei (Tokyo, 1852-1918) A goose in flight, (sakatsuragan) preparing to reach the water, but looking for a quiet landing space, with calmer wawes. 1900s. Signed Seitei, sealed Seitei. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 115,5 x 47,6 cm. CP 329

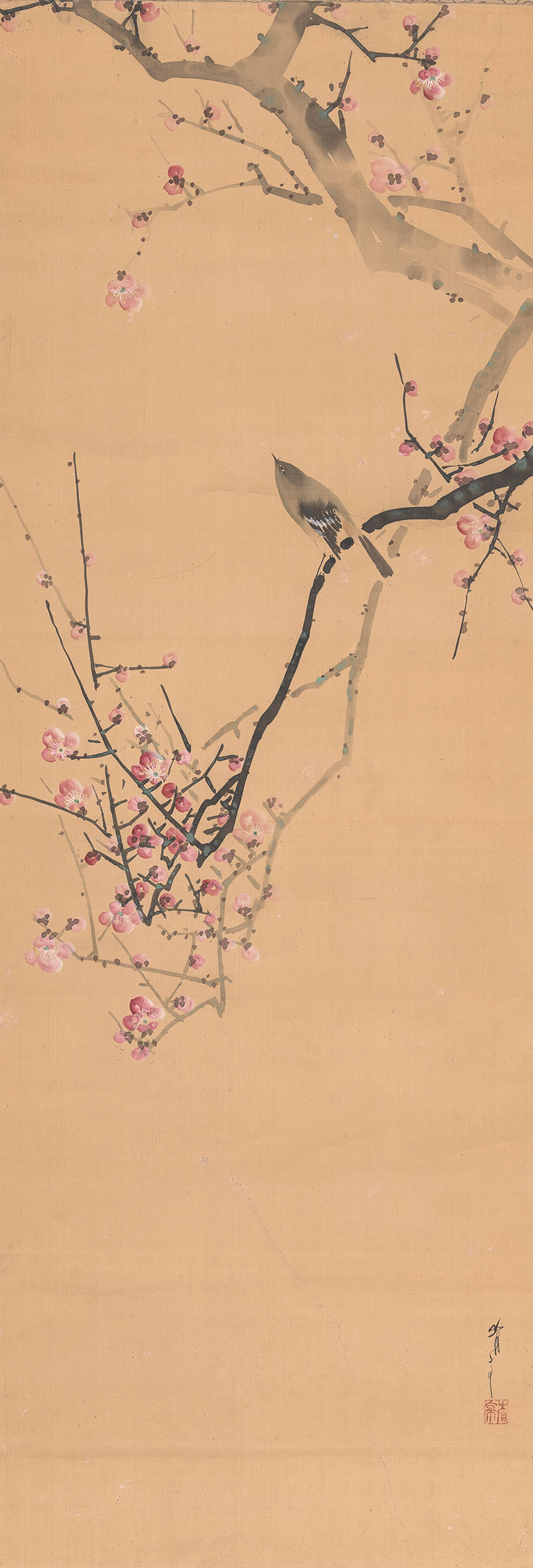

“Bush warblers are associated with spring, and ideally

we see them on budding plum trees, which bloom

during the first month in the lunar calendar”

Watanabe Seitei (Tokyo, 1852-1918) A bush warbler (uguisu) on a branch of a flowering plum (ume), as a very traditional subject for the beginning of spring. 1910s. Signed Seitei, sealed Seitei. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 118,7 x 41,2 cm. CP 361

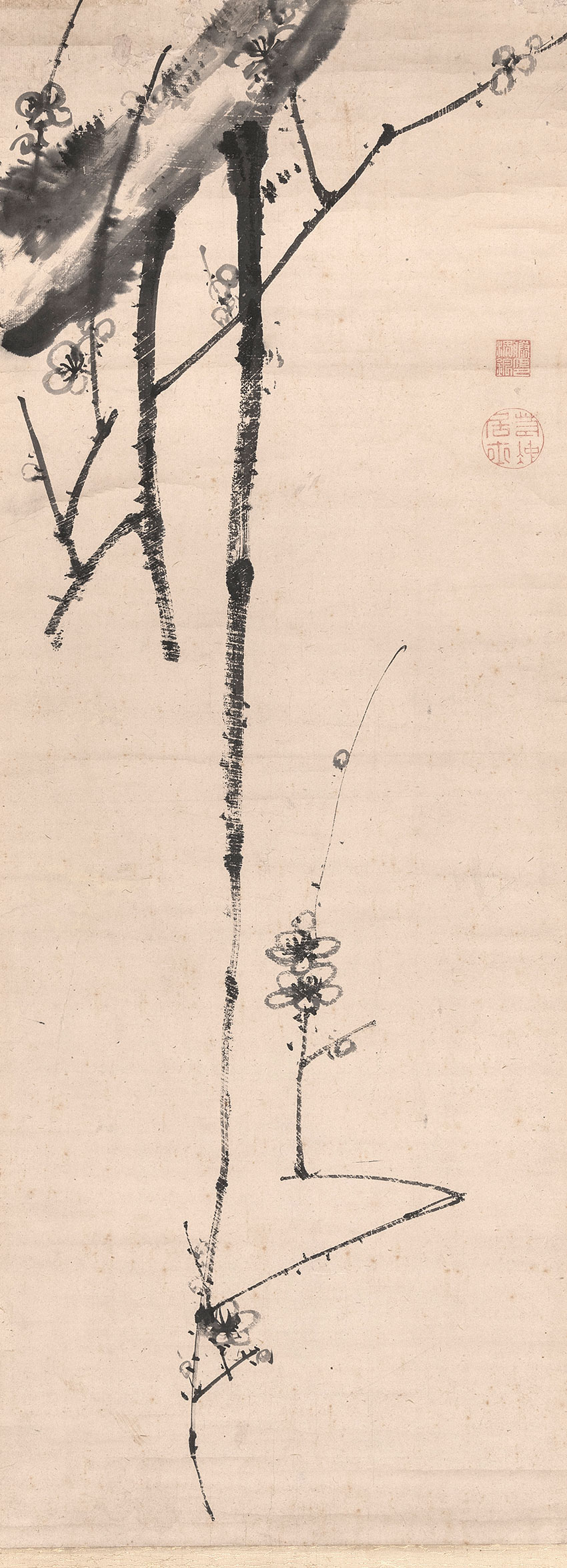

“Flowering cherry trees, symbols of impermanence,

are naturally associated with the third month”

It ¯o Jakuch¯u (1716-1800) An almost calligraphic handling of branches of a flowering plum (ume) seen in close up, suggesting that spring has come. Circa 1760. Unsigned, sealed T ¯o Jokin, Jakuch¯u koji. Painting in ink on paper, 116,3 x 42,3 cm. CP 016

“Bamboo and sparrows too are often seen together”

Tomioka Tessai (Kyoto, all over Japan, 1837-1924) Some stalks of bamboo grass (sasa or yadake) and a young sprout. Tessai added the text ‘Cool Breeze and Lofty Virtues (Seif ¯u k ¯osetsu)’ as a motto for the painting. 1860s-70s. Signed Tessai Gakujin, sealed Tessai koji/Tomioka Hyakuren. Painting in ink on paper, 131,5 x 49,7 cm. CP 398

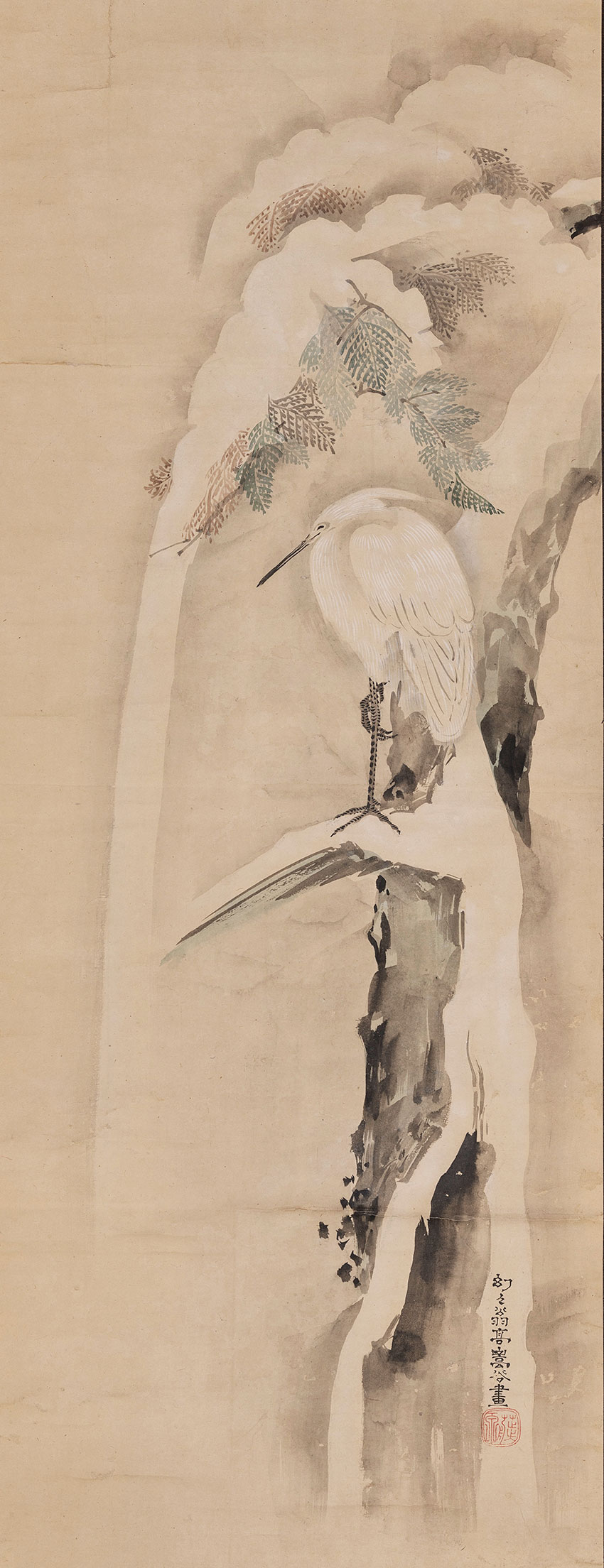

“Herons are usually connected with summer

but we find them in winter settings too”

K¯o S ¯ukoku (Edo, 1730-1804) A white heron (kosagi) on the branch of a snow-laden evergreen hiba (asunaro; Thujopsis dolabrata), obviously associating the scene with winter. Dated 1804. Signed ‘Seventy-five Years Old K¯o S ¯ukoku (Nanaj ¯ugo no ¯o K¯o S ¯ukoku),’ sealed T¯osen (?). Painting in ink and colours on paper, 100,2 x 38 cm. CP 220

A kingfisher

by Kan¯o Tsunenobu

Kan¯o Tsunenobu (Edo, 1636-1713) A kingfisher (kawasemi) having selected a lotus pod (hasu) for its position to catch some fish to eat. With the lotus flowers being associated with summer, it seems most likely that this painting, featuring the withered pod with its seeds, would be more appropriate for display in autumn. Late 17th century. Signed Tsunenobu, sealed Ukon. Painting in ink on paper, 27,8 x 46,1 cm. CP 665

“Cranes would seem to be birds for all seasons,

even though they hibernate elsewhere. Their images are often

used to celebrate the New Year and bring good luck”

Maruyama O ¯ kyo (Kyoto, 1733-1795) Part of a diptych of two cranes (tanch ¯ozuru) one looking down, probably looking for something to eat (right), and the other looking up, its neck and head stretched. Early 1760s. Both unsigned and sealed O ¯ kyo/Chu¯ sen. Pair of paintings in ink and some colour on paper, 120,5 x 52,4 cm each. CP 518

Maruyama O ¯ kyo (Kyoto, 1733-1795) Part of a diptych of two cranes (tanch ¯ozuru) one looking down, probably looking for something to eat (right), and the other looking up, its neck and head stretched. Early 1760s. Both unsigned and sealed O ¯ kyo/Chu¯ sen. Pair of paintings in ink and some colour on paper, 120,5 x 52,4 cm each. CP 518

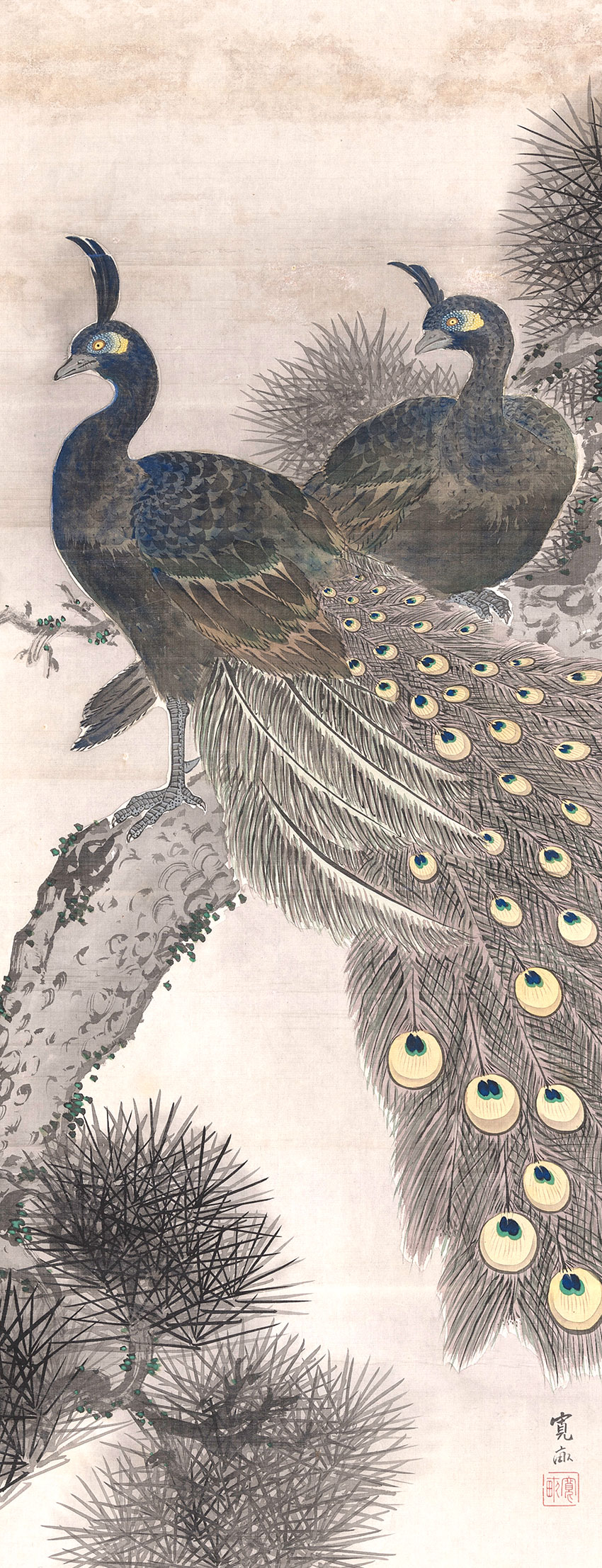

“Outlandish exotic birds, (i.e. peacocks) mostly introduced in Japan

by the Dutch traders, have always been of special interest”

Araki Kanpo (Edo/Tokyo, 1831-1915) A pair of peacocks (kujaku), male and a female, on a pine tree (kuromatsu). Peacocks were imported from abroad and, in the Edo Period, were a favourite with the samurai class that would keep them in their aviaries. Late 19th century. Signed Kanpo, sealed Kanpo. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 102,6 x 39,6 cm. CP 675

“We must finally remember that these seasonal associations, for both birds and flowers, have their origin in poetry. The short haiku composition, for example, always includes such clues, that can be understood by everyone”.

![]() Comment by Matthi Forrer

Comment by Matthi Forrer

“In most Japanese painting traditions, figures are restricted to some images of Buddhist deities, such as Bodhidharma, the founder of the Zen sect, some followers or disciples of the Buddha, portraits of renowned abbots, as well as some Shintoist figures, such as the gods of Wind and Thunder, or figures adopted from the Chinese tradition, such as the monks Kanzan and Jittoku who lived at some monastery, and the protective mythical Sh¯ oki, the demon queller”.

“It is only in the eighteenth and nineteenth century urban traditions of Shij ¯ o-Maruyama in Kyoto, and in the Ukiyo-e tradition of Edo, that commoners begin to make their appearance in painting”.

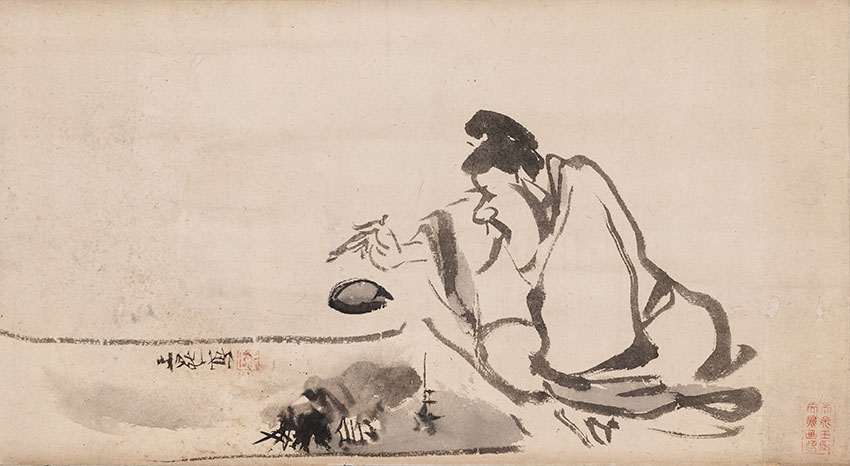

A self-portrait of the artist

by Tani Bunch¯o

Tani Bunch¯o (Edo, 1763-1841) A self-portrait of the artist, with a brush in his hand and an inkstone at his side, working on a painting of a landscape. This is obviously not a commissioned painting, and we can only speculate that this served as a message to some client or friend to inform him that he was actually working on his ommission. Dated 1832. Unsigned, sealed ‘By Bunch¯o, in the Year of the Dragon in the Tenp¯o Period (Tenp¯o mizunoe tatsu Bunch¯o ga),’ 1832. Painting in ink on paper, 27 x 49,2 cm. CP 346

A geisha holding a parasol under a maple tree

by Kaburagi Kiyokata

Kaburagi Kiyokata (Tokyo, 1878-1972) A geisha holding a parasol under a maple tree (momiji). The maple would suggest a link with autumn, but for the author, nostalgia for the past may well have been much more important. 1920s-30s. Signed Kiyokata, sealed Seik¯o. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 45,7 x 50,9 cm CP 257

![]() Comment by Matthi Forrer

Comment by Matthi Forrer

“In comparison with birds, all other animals only represent a smaller category in Japanese paintings of the natural world. Of course you will find deer, squirrels, foxes, puppy dogs, cats, and badgers, but we probably have the best chance among the Twelve Animals of the Eastern Zodiac”. “However, oxen, tigers, hares, horses, goats, monkeys, snakes and even dragons hardly figure in paintings in their role of being part of this cycle”.

Monkeys. “Are represented in awkward situations where, for example, a mother wasp or bee comes looking for its larvae or honey that the primates are eating”.

A monkey on a rock

by Watanabe Nangaku

Watanabe Nangaku (Kyoto, Edo 1767-1813) A monkey on a rock, probably alarmed by the buzzing of a wasp, flying underneath the rock. 1790s. Signed Nangaku, sealed Iwao/Iseki. Painting in ink and some colour on silk, 111 x 47,8 cm. On the inside of the lid of the box is an inscription certifying the painting, by the painter Nishiyama Kanei (1834-1897), dated 1864. CP 051, on loan at MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Turin, Italy, inv. Jd/49.D

A family of monkeys

by Mori Sosen

Mori Sosen (Osaka, 1747-1821) A family of monkeys (saru) gathered on a rock under a pine tree (matsu). The mother is taking care of their young child, as the father is alarmed by a wasp. Late 18th century. Signed Sosen, sealed To Morikata, or Shush¯o. Painting in ink and colours on silk, 108 x 37,9 cm. CP 167

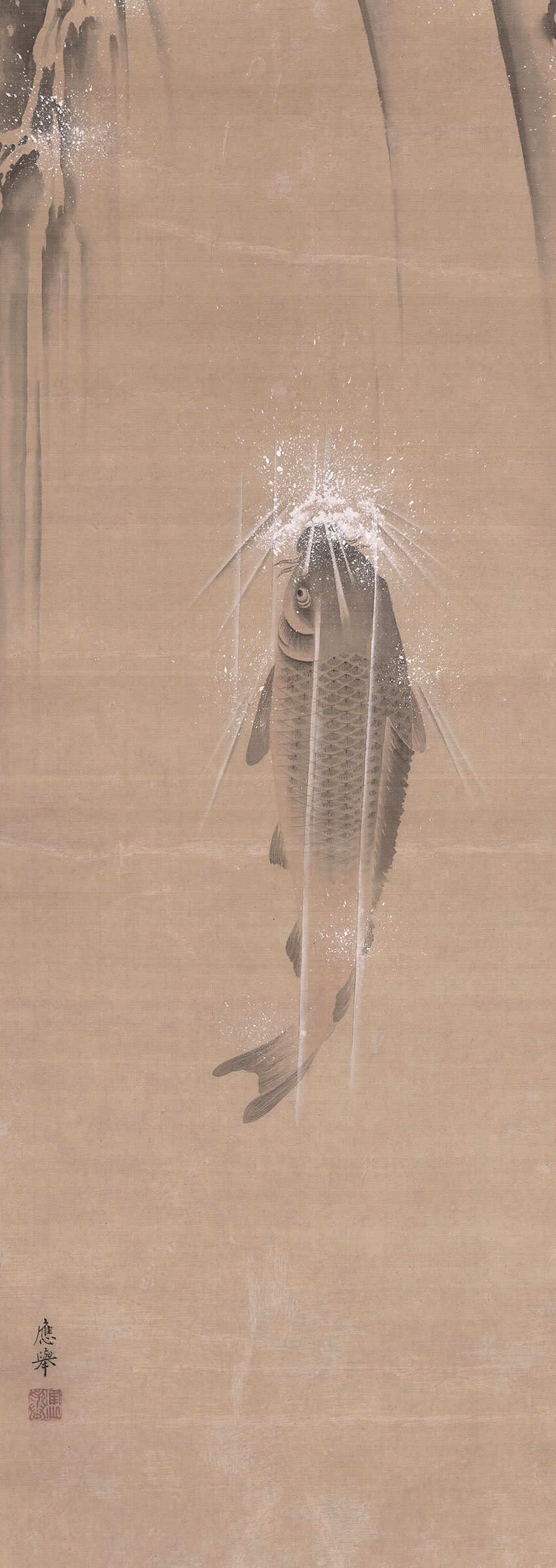

Carp. “Are emblematic of perseverance, and a model for boys to rise to fame and fortune. This notion is based on the belief that carp, when manage to ascend a waterfall and leap through the Dragon Gate, may transform into dragons themselves”.

A carp ascending a real wide waterfall

by Maruyama O ¯ kyo

Maruyama O¯kyo (Kyoto, 1733-1795) A carp ascending a real wide waterfall, hoping to be able to leap through the Dragon Gate and transform into a dragon itself. Circa 1785. Signed O ¯ kyo, sealed O ¯ kyo. Painting in ink and some colour on silk, 98,3 x 35,1 cm. CP 039

Maruyama O¯kyo (Kyoto, 1733-1795) A carp ascending a real wide waterfall, hoping to be able to leap through the Dragon Gate and transform into a dragon itself. Circa 1785. Signed O ¯ kyo, sealed O ¯ kyo. Painting in ink and some colour on silk, 98,3 x 35,1 cm. CP 039

A carp ascending a waterfall

by Maruyama O¯zui

Maruyama O¯zui (Kyoto, 1766-1829) A carp ascending a waterfall. Dated V/1799. Signed O ¯ zui, sealed O ¯ zui. Dated ‘Mid-summer of the Year of the Goat in the Kansei Period (Kansei hitsuji ch ¯uka),’ V/1799. Painting in ink on silk, 103,1 x 31,8 cm. It is interesting to compare this painting with a very similar one by O¯kyo, dated 1789, kept at the Daij¯oji Temple in Hy¯ogo. CP 047, on loan at MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Turin, Italy, inv. Jd/13.D

A carp ascending a waterfall

by Watanabe Seitei

Watanabe Seitei (Tokyo, 1852-1918) A carp ascending a waterfall, and a rock overgrown with maple trees (momiji) to the right, suggesting an autumn scene. 1870s. Signed Seitei, sealed Ry¯osuke/Ry¯o. Painting in ink and colours on paper, 136,5 x 49,3 cm. CP 283

Watanabe Seitei (Tokyo, 1852-1918) A carp ascending a waterfall, and a rock overgrown with maple trees (momiji) to the right, suggesting an autumn scene. 1870s. Signed Seitei, sealed Ry¯osuke/Ry¯o. Painting in ink and colours on paper, 136,5 x 49,3 cm. CP 283

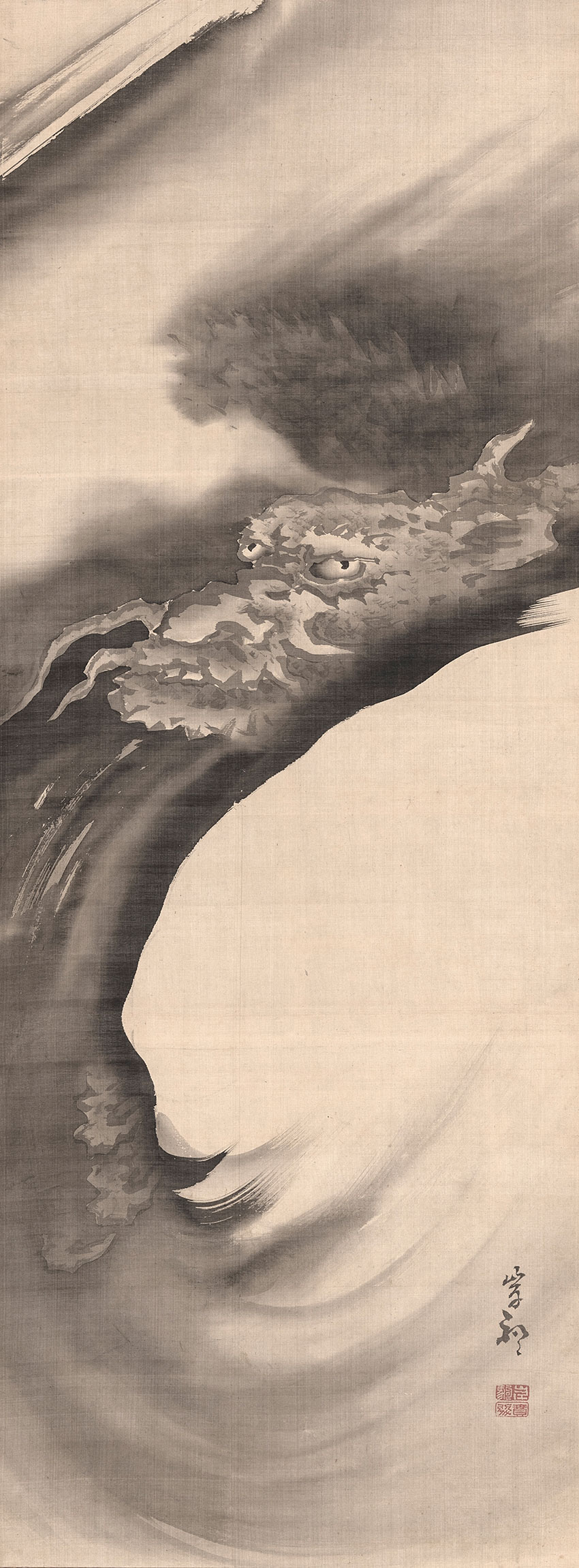

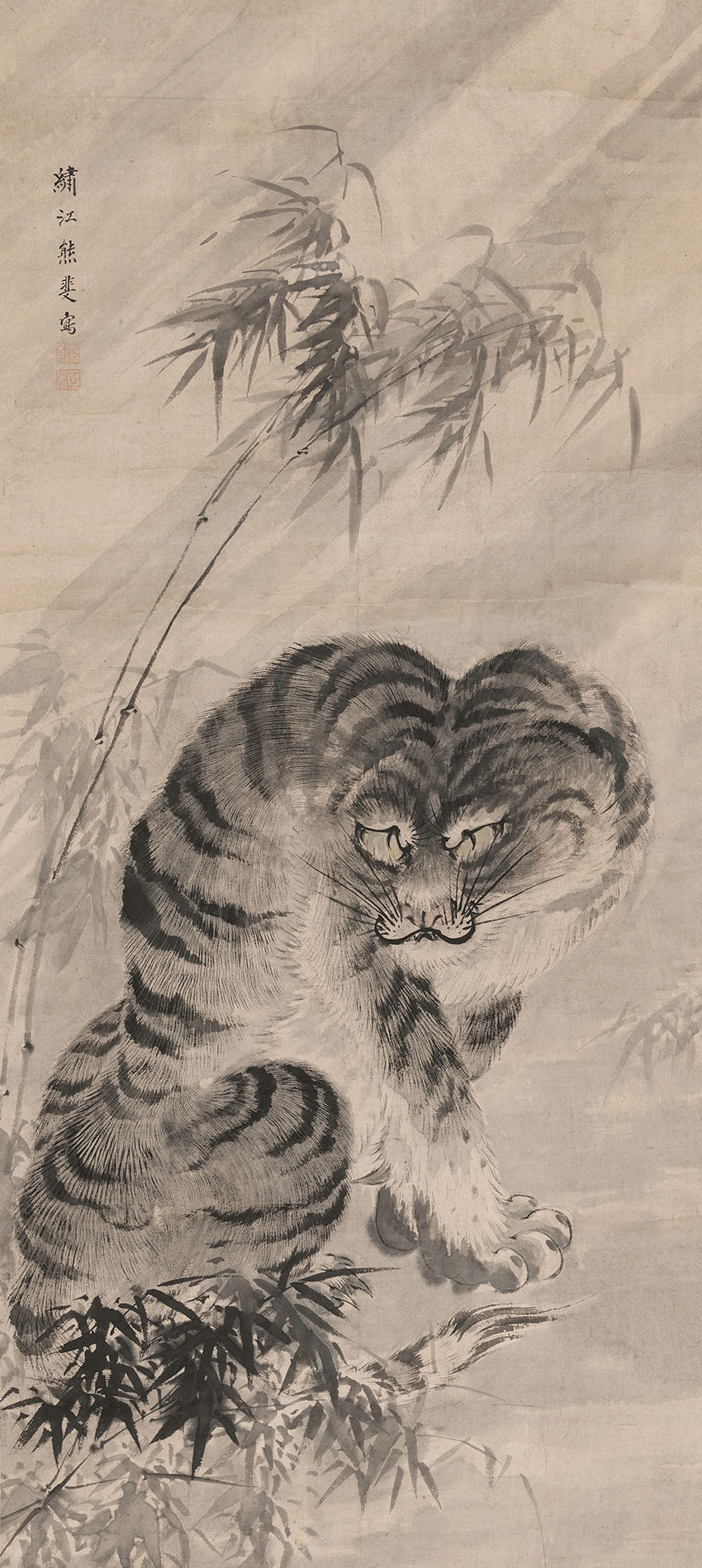

Dragons. “Are a Chinese mythological creation, with the head of a camel, horns of a deer, scales of a carp, and paws of a tiger. They are believed to act as messengers to the gods, as they live in the sea but can also ascend to the sky, representing Spirit and Heaven. But anyone, seeing the animal in its entirety, will die instantly, which is why part of their body is always obscured in paintings. “In images, they are often combined with a tiger, equally of Chinese origin, representing Matter and Earth”.

A dragon, in two of its typical elements,

the waves, where dragons live, and the clouds

by Kishi Ganku

Kishi Ganku (Kyoto, 1749, or 1756-1839) A dragon, in two of its typical elements, the waves, where dragons live, and the clouds, where they can ascend to heaven, and serve as messengers to the gods. 1785-1808. Signed Ganku, sealed Ganku/Funzen. Painting in ink on silk, 95,5 x 35,4 cm. CP 433

A tiger seeking shelter under a rock

by Watanabe Kazan

Watanabe Kazan (Edo, 1793-1841) A tiger seeking shelter under a rock overgrown with bamboo grass (sasa or yadake), an image combining the strength of the animal with the pliancy of bamboo, bending even in storms. 1810s. Signed Kazan, sealed Kazan. Painting in ink and colours on paper, 125 x 52,5 cm. With authenticating inscription on the back by Tsubaki Chinzan (1801-1854). CP 448

Watanabe Kazan (Edo, 1793-1841) A tiger seeking shelter under a rock overgrown with bamboo grass (sasa or yadake), an image combining the strength of the animal with the pliancy of bamboo, bending even in storms. 1810s. Signed Kazan, sealed Kazan. Painting in ink and colours on paper, 125 x 52,5 cm. With authenticating inscription on the back by Tsubaki Chinzan (1801-1854). CP 448

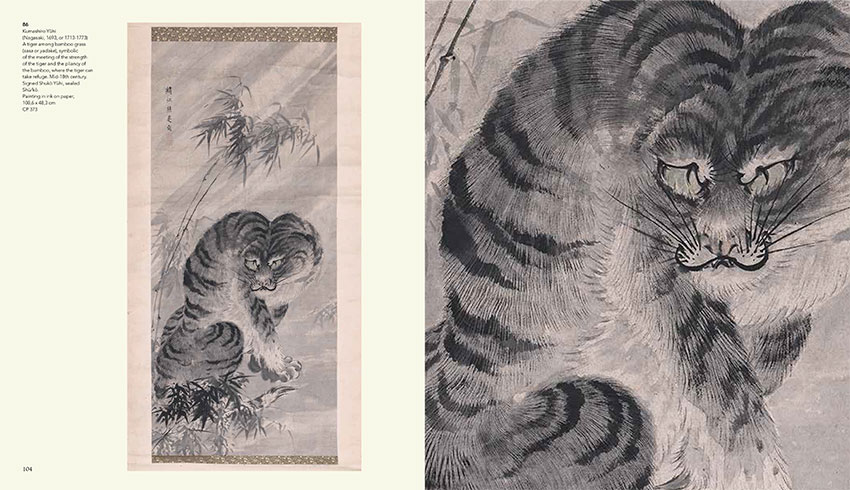

A tiger among bamboo grass

by Kumashiro Y¯uhi

Kumashiro Y¯uhi (Nagasaki, 1693, or 1713-1773) A tiger among bamboo grass (sasa or yadake), symbolic of the meeting of the strength of the tiger and the pliancy of the bamboo, where the tiger can take refuge. Mid-18th century. Signed Shuk¯o Y¯uhi, sealed Sh¯u/k ¯o. Painting in ink on paper, 108,6 x 48,3 cm. CP 373

Kumashiro Y¯uhi (Nagasaki, 1693, or 1713-1773) A tiger among bamboo grass (sasa or yadake), symbolic of the meeting of the strength of the tiger and the pliancy of the bamboo, where the tiger can take refuge. Mid-18th century. Signed Shuk¯o Y¯uhi, sealed Sh¯u/k ¯o. Painting in ink on paper, 108,6 x 48,3 cm. CP 373

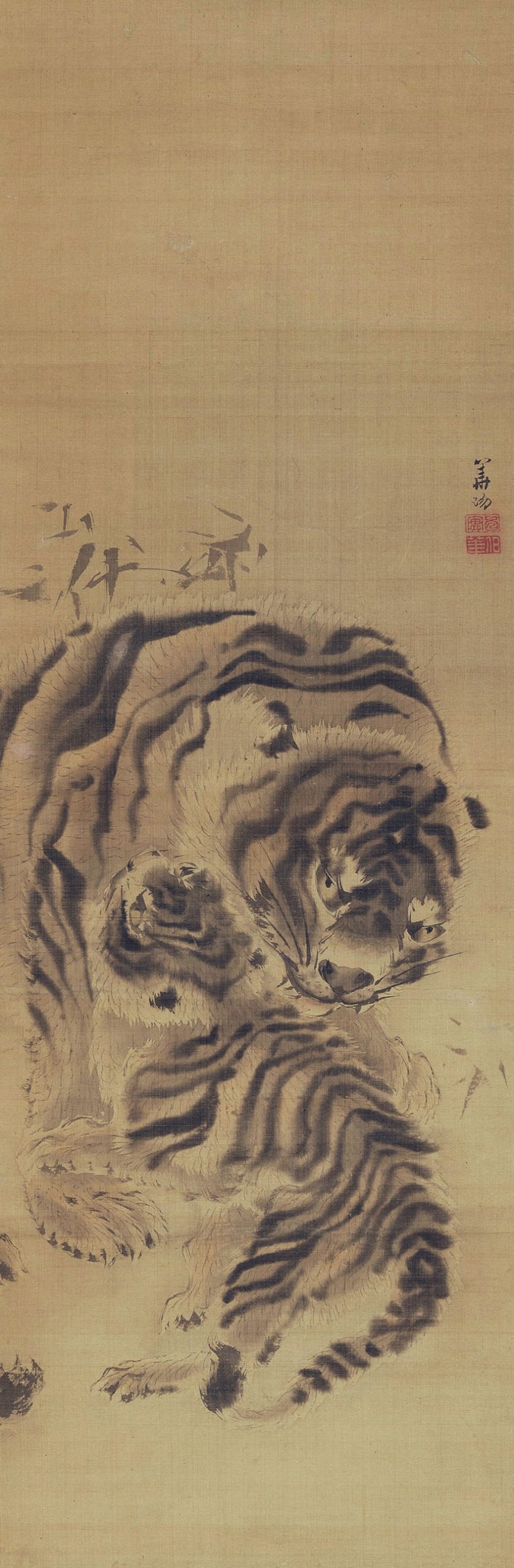

A tigress licking her cub

by Kishi Ganku

Kishi Ganku (Kyoto, 1749, or 1756-1839) A tigress licking her cub. This is a rare example of a painting of the private life of tigers, most likely based on his study of the tigers kept by Prince Arisugawa, an important patron of Ganku from 1784. 1784-90. Signed Kay¯o, sealed [unread]/Hakka. Painting in ink on silk, 97,3 x 31,6 cm. CP 117

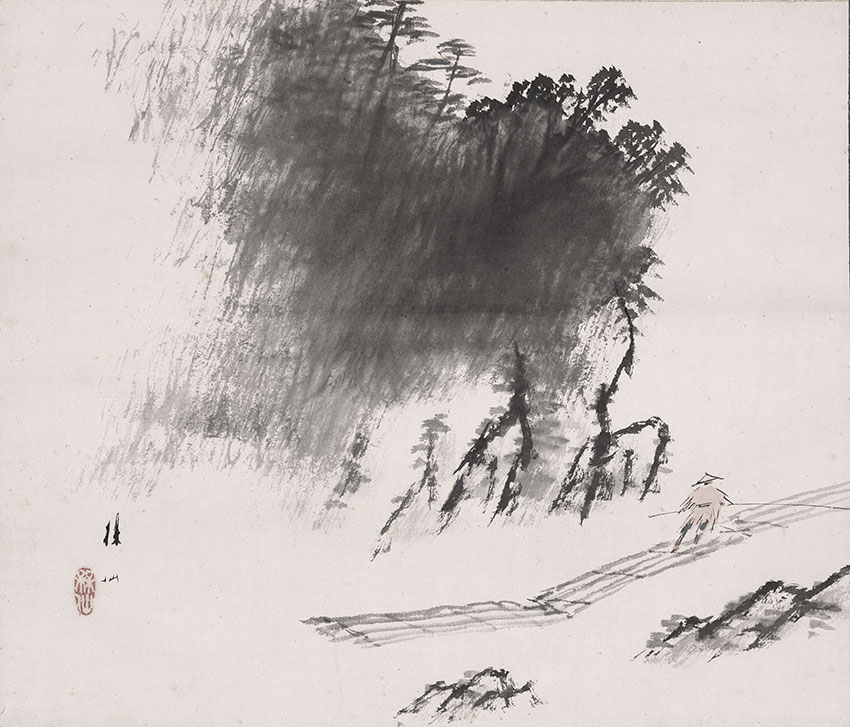

![]() Comment by Matthi Forrer

Comment by Matthi Forrer

“In paintings – and this is quite different from the woodblock prints of the nineteenth century – most landscapes represent an ideal of some kind, and only few show real places and famous scenic views”

A man poling a raft on the O¯i. River at Arashiyama

by Hirai Baisen

Hirai Baisen (Kyoto, 1889-1969) A man poling a raft on the O¯i. River at Arashiyama, near Kyoto. 1950s. Signed Baisen, sealed Baisen. Painting in ink and some colour. on paper, 35,3 x 41,3 cm. CP 188

A view of the snow-covered summit of Mount Fuji rising above the mist

by Okamoto Toyohiko

Okamoto Toyohiko (Kyoto, 1773-1845) A view of the snow-covered summit of Mount Fuji rising above the mist. 1840s. Signed Toyohiko, sealed Toyohiko. Painting in ink and colour on silk, 107,6 x 41,4 cm. CP 583

![]()

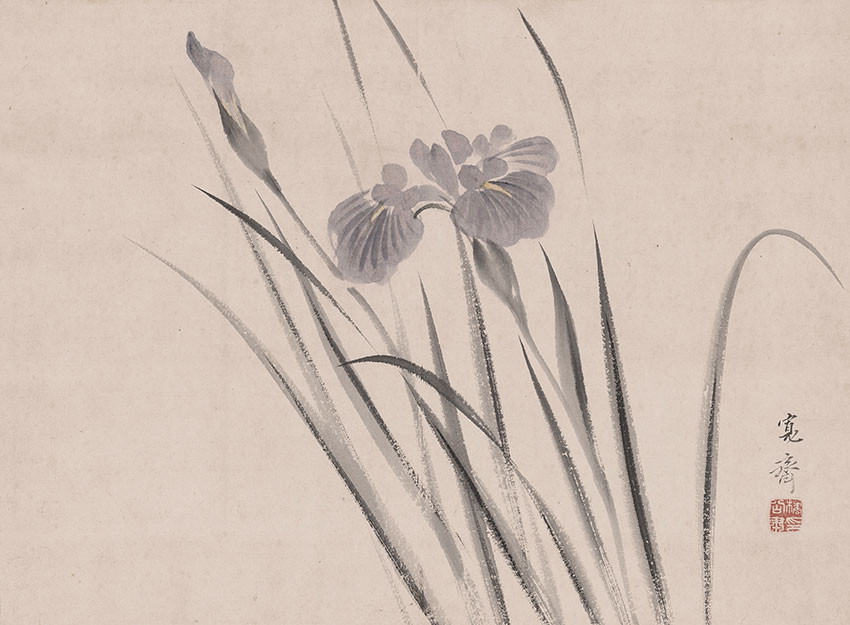

“It is, of course, quite logical that plants and flowers, as well as flowering trees and shrubs, would be even more closely associated with specific months than birds. Birds may be around for most of the year, but, on the other hand, we can only enjoy flowering plum trees in the first lunar month, and cherries in bloom in the third month”.

Some irises (hanash¯obu) blowing in the wind

by Mori Kansai

Mori Kansai (Osaka, Kyoto, 1814-1894) Some irises (hanash¯obu) blowing in the wind. Irises are associated with summer and especially with the Fifth Month. 1850s-60s. Signed Kansai, sealed Tachibana K¯oshuku. Painting in ink and colours on paper, 29,5 x 39,9 cm. CP 281

A quite uncommon representation

of a white magnolia (mokuren) and a branch of willow

by Tanomura Chikuden

Tanomura Chikuden (Bungo, 1777-1835) A quite uncommon representation of a white magnolia (mokuren) and a branch of willow (yanagi) in a vase. This probably represents a simple manner of displaying flowers in the house, quite unlike the much more artificial ikebana flower arrangements. Dated IV/1834. Signed Chikuden, sealed Chikuden. Dated ‘Fourth Month of the year of the Horse (Kinoe uma nao seiwazuki),’ IV/1834.Painting in ink and colours on paper, 85,3 x 24,9 cm. CP 148

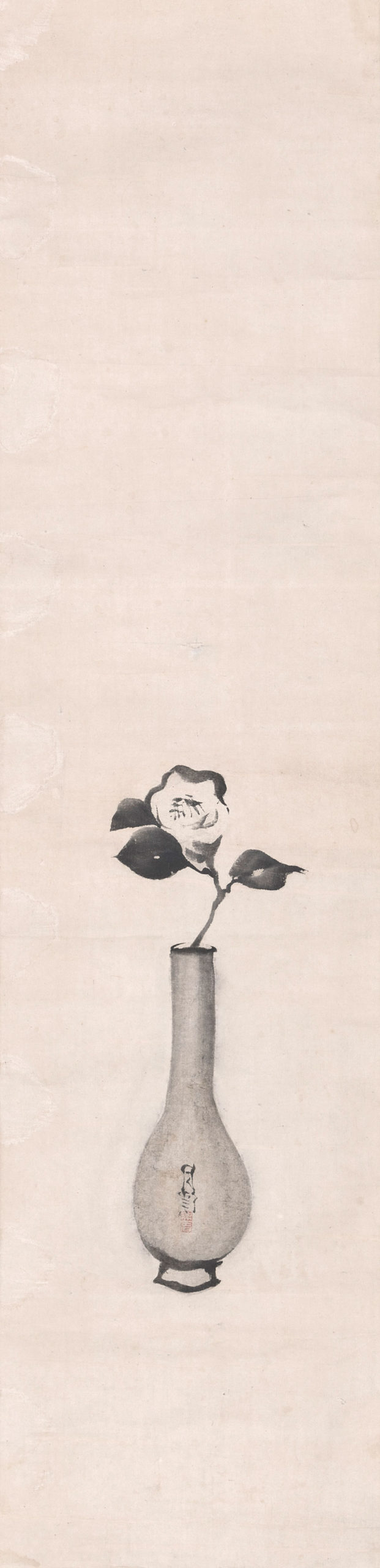

A branch of white camellia (tsubaki) in a vase

by Matsumura Gekkei

Matsumura Gekkei, better known as Goshun (Settsu, Kyoto, 1752-1811) A branch of white camellia (tsubaki) in a vase, associating the painting with spring. 1780s. Signed Gekkei, sealed Goshun. Painting in ink on paper, 99,3 x 24,2 cm. CP 464

![]()

Claudio Perino

Claudio Perino began collecting more than three decades ago. His passion for Japanese art objects has led him to patiently collect and come to possess one of the most important private collections of Japanese art, where the exceptional pieces of Kakemono presented in this exhibition stand out. Claudio Perino is among the main lenders and patrons of MAO, Museo d’Arte Orientale di Torino.

Claudio Perino began collecting more than three decades ago. His passion for Japanese art objects has led him to patiently collect and come to possess one of the most important private collections of Japanese art, where the exceptional pieces of Kakemono presented in this exhibition stand out. Claudio Perino is among the main lenders and patrons of MAO, Museo d’Arte Orientale di Torino.

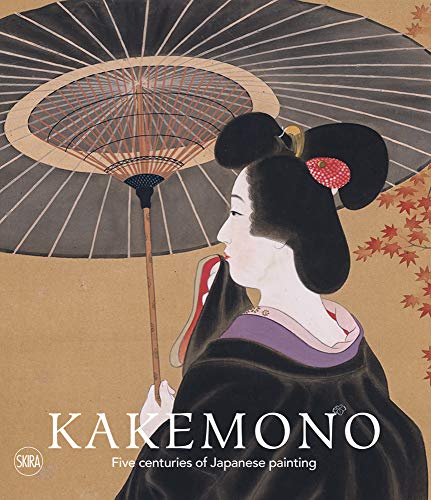

CATALOGUE

CATALOGUE

![]()

Five centuries of Japanese painting.

The Perino Collection

Author and editor: Matthi Forrer

125 images of Kakemono in color

Pages: 208

Size: 26,5×23 cm

Softcover

ISBN: 978-88-572-4379-5

37€

Edition produced by SKIRA that reproduces all 125 Kakemo from the Claudio Perino Collection presented in the exhibition. Author Matthi Forrer, Professor of Material Culture of Pre-modern Japan at Leiden University provides a comprehensive and scholarly history of the Kakemono in Japanese culture.

Marco Guglielminotti Trivel, East Asia Curator, MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Turin and Francesco Paolo Campione, Director of the Museo delle Culture, Lugano, write the forewords to this edition. Moira Luraschi of the Museo delle Culture Lugano, presents an interview with the collector Claudio Perino on the occasion of the exhibition Kakemono.

© 2020 Fondazione culture e musei, Lugano

© 2020 Fondazione Torino Musei

© 2020 Skira editore

Examples of inside pages

MUSEO D’ARTE ORIENTALE

Via San Domenico, 11. 10122 Turin, Italy

https://www.maotorino.it/it