K Y O T O

CAPITAL OF ARTISTIC IMAGINATION

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Until January 31, 2021

Focusing on the main turning points in the cultural history of Kyoto from ancient to modern times, the exhibition places special emphasis on the decorative arts. Over eighty masterworks of lacquers, ceramics, metalwork, and textiles from The Met collection, including a number of recently acquired works of contemporary art are showcased.

PATRONS has selected some of the most outstanding masterpieces of the exhibition to show in this article.

S C R E E N S

御所車図

IMPERIAL CARTS (Gosho guruma)

mid-17th century

Imperial Carts (Gosho guruma). mid-17th century, Edo period (1615–1868). Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, 65 3/4 in. × 12 ft. 4 1/2 in. (167 × 377.2 cm). Gift of Mrs. P. H. B. Frelinghuysen, 1962.

Imperial Carts (Gosho guruma). mid-17th century, Edo period (1615–1868). Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, 65 3/4 in. × 12 ft. 4 1/2 in. (167 × 377.2 cm). Gift of Mrs. P. H. B. Frelinghuysen, 1962.

Details of the Screen of the Imperial Carts

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

Comments: “In ancient and medieval Kyoto, the imperial family and nobility rode in carriages drawn by oxen. In this depiction of three carriages, lowered bamboo blinds tantalizingly suggest the presence of an elegant lady or nobleman. This image alludes to several classic literary scenes, among them an event from the “Leaves of Wild Ginger” (Aoi) chapter in The Tale of Genji, in which attendants of Genji’s wife and his former lover create a crush of carts as they compete for the best position from which to view the Kamo festival in Kyoto.

Such beautifully appointed vehicles, decorated with a wild ginger motif, were a popular subject for decorative art objects and textiles. Lacking evidence of a dispute, the composition is a decorative representation of carts set among the delicate pink blossoms of early summer. The painting convention of omitting human presence, common in the decorative arts, came to be called the “motif of absence” (rusu moyō)”.

誰ヶ袖図屏風

Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”)

first half of the 17th century

Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”), first half of the 17th century, Momoyama (1573–1615) or Edo (1615–1868) period. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, silver, and gold leaf on paper, Overall (each screen): 59 1/4 x 10 ft. 10 11/16 in. (150.5 x 332 cm). H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Mrs. Dunbar W. Bostwick, John C.

Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”), first half of the 17th century, Momoyama (1573–1615) or Edo (1615–1868) period. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, silver, and gold leaf on paper, Overall (each screen): 59 1/4 x 10 ft. 10 11/16 in. (150.5 x 332 cm). H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Mrs. Dunbar W. Bostwick, John C.

Details of the Screen of Tagasode

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

Comments: “In classical love poetry the phrase Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”) refers to an absent woman whose beautiful robes evoke memories of their owner. A number of screens bearing this sobriquet depict sumptuously patterned kimonos draped over lacquered clothing stands. This example displays fashionable textile patterns of the late sixteenth through early seventeenth century. Some of the robes have delicate tie-dyed patterns (“fawn spots,” or kanoko shibori), representing the refinement of Kyoto taste. Beginning in the medieval period, Kyoto was known for its textile industry, centered in what is now the Nishijin district. Empress Consort Tōfukumon’in (1607–1678), wife of Emperor Go-Mizunoo (1596–1680), frequently ordered richly ornamented garments from Kariganeya, a textile shop catering to the old aristocracy, and her purchases initiated official imperial patronage of Kyoto textiles. These screens were recently rebuilt and restored in the Department of Asian Art’s conservation studio with funding from Patricia Saigo and others”.

誰ヶ袖図屏風

Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”)

first half of the 17th century

Tagasode (“Whose Sleeves?”), first half of the 17th century, Momoyama (1573–1615) or Edo (1615–1868) period. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, silver, and gold leaf on paper, Overall (each screen): 59 1/4 x 10 ft. 10 11/16 in. (150.5 x 332 cm). H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Mrs. Dunbar W. Bostwick, John C.

Details of the Screen of Tagasode

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

狩野光信周辺 四季花草図屏風

Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons

late 16th century

Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons, late 16th century. Circle of Kano Mitsunobu (Japanese, 1565–1608), Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper, Each: 59 15/16 in. × 11 ft. 7 7/16 in. (152.3 × 354.2 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke

Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons, late 16th century. Circle of Kano Mitsunobu (Japanese, 1565–1608), Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper, Each: 59 15/16 in. × 11 ft. 7 7/16 in. (152.3 × 354.2 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke

Details of Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

Comments: “In this lyrical variation of the common theme of Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons, delicately rendered insects such as dragonflies, butterflies, and praying mantises hover among kerria roses, peonies, chrysanthemums, bush clover, and snow-dusted lantern flowers. Scallop-edged golden clouds and the graceful arcs of eulalia grasses form repeating, rhythmic patterns. The treatment of pictorial elements is consistent with the gentle, elegant painting style of Kano Mitsunobu, whose works graced a number of Kyoto palaces and temples. Parallels can also be drawn to lacquer decoration at the mausoleum of warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in Kyoto’s Kōdaiji Temple. The lacquered and maki-e–decorated panels, associated with the Kōami school of Kyoto lacquer artisans, display repeating autumn grasses resembling motifs in Mitsunobu’s paintings and this pair of screens”.

四季花鳥図屏風

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons

late 16th century

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, late 16th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, Image: 63 1/4 in. × 11 ft. 10 in. (160.7 × 360.7 cm). Mrs. Jackson Burke and Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Gifts, 1987.

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, late 16th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, Image: 63 1/4 in. × 11 ft. 10 in. (160.7 × 360.7 cm). Mrs. Jackson Burke and Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Gifts, 1987.

Details of Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

Comments: “This composition of flowers in a seasonal progression from spring to winter celebrates longevity with its auspicious motif of cranes. The brilliant colors, strong outlines in black ink, and profusion of pictorial elements are typical of the decorative formula established by Kano Motonobu (1476–1559), founder of the Kano school. The boldness, however, is more reminiscent of Motonobu’s grandson, the prolific Kano Eitoku (1543–1590), and the treatment of branches is closer to Eitoku’s style than to that of Motonobu’s other successors. The exaggerated dimensions of the pine and cedar trees, the attempt to create space for the projecting branches in the crowded composition, and the depiction of brushwood hedges in high relief suggest that the work dates to the late sixteenth century.”

四季花鳥図屏風

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons

late 16th century

Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, late 16th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, Image: 63 1/4 in. × 11 ft. 10 in. (160.7 × 360.7 cm). Mrs. Jackson Burke and Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Gifts, 1987.

Details of Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

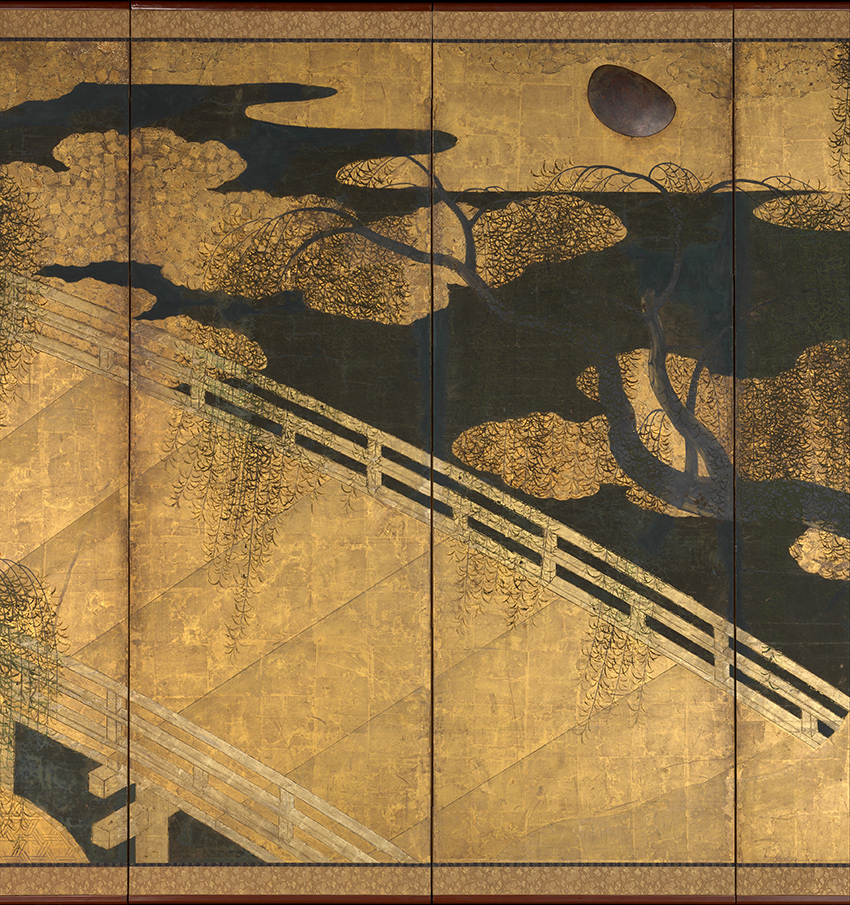

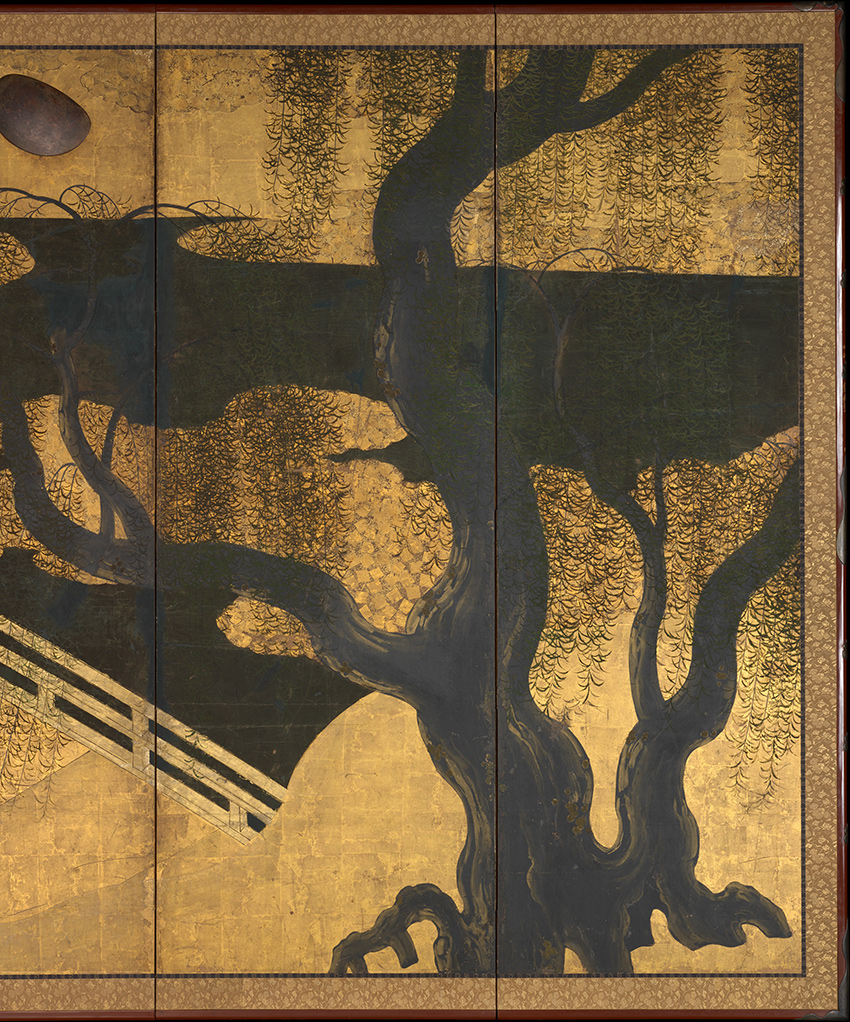

柳橋水車図屏風

Willows and Bridge

early 17th century

Willows and Bridge, early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, copper, gold, and gold leaf on paper, Image (each): 61 5/16 in. × 11 ft. 5/16 in. (155.8 × 336 cm) Overall (each): 67 5/8 in. × 11 ft. 6 9/16 in. (171.8 × 352 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

Willows and Bridge, early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, copper, gold, and gold leaf on paper, Image (each): 61 5/16 in. × 11 ft. 5/16 in. (155.8 × 336 cm) Overall (each): 67 5/8 in. × 11 ft. 6 9/16 in. (171.8 × 352 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

Comments: “Paintings that combine willows with a bridge and waterwheel immediately evoke the bridge over the Uji River in southeast Kyoto, a view long celebrated in literary works such as The Tale of Genji. Paintings of the Uji Bridge decorated palaces by the 900s and remained popular for the next thousand years. With their contrast of large, dramatic forms and brilliant metallic shimmer, these screens represent the zenith of the decorative style of the late sixteenth century. Above the golden bridge’s strong diagonal is a copper moon, attached to the screen by small pegs. A large waterwheel turns in the stream and stone-filled baskets protect the embankments. Gently lapping waves of silver pigment have oxidized over time to a dark gray”.

Details of Willows and Bridge

DETAIL OF LEFT PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF CENTER PANEL GROUP

DETAIL OF RIGHT PANEL GROUP

P A I N T I N G S

南宋 佚名 倣夏珪 冒雨尋莊圖 團扇

Returning Home in a Driving Rain

early 13th century

Returning Home in a Driving Rain, early 13th century. After Xia Gui (Chinese, active ca. 1195–1230). Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Fan mounted as an album leaf; ink and color on silk, 10 1/16 x 10 3/8 in. (25.6 x 26.4 cm). The Dillon Fund Gift, 1982.

Returning Home in a Driving Rain, early 13th century. After Xia Gui (Chinese, active ca. 1195–1230). Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Fan mounted as an album leaf; ink and color on silk, 10 1/16 x 10 3/8 in. (25.6 x 26.4 cm). The Dillon Fund Gift, 1982.

Detail of Returning Home in a Driving Rain

Comments: “This composition, formerly attributed to the painter Xia Gui, depicts two farmers struggling to return home in a summer downpour. Although the drawing of the angry cliff face and dancing tree leaves is extremely skillful, the effect is somewhat theatrical. The round brushwork, while derived from Xia Gui, is from a different hand, probably that of a close follower. Paintings by Southern Song Chinese painters like Xia Gui were treasured in medieval Japan and collected by shoguns in Kyoto. On view February 8–October 25, 2020”.

狩野孝信筆 布袋図「拄杖擊破三千界。彌勒撫掌笑呵呵,明月清風無。」

Hotei, 1616

Hotei, 1616, by Kano Takanobu (Japanese, 1571–1618), Calligrapher: Tetsuzan Sōdon (Japanese, 1532–1617). Edo period (1615–1868). Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper, 27 1/2 x 15 in. (69.9 x 38.1 cm). Funds from various donors, 2006.

Hotei, 1616, by Kano Takanobu (Japanese, 1571–1618), Calligrapher: Tetsuzan Sōdon (Japanese, 1532–1617). Edo period (1615–1868). Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper, 27 1/2 x 15 in. (69.9 x 38.1 cm). Funds from various donors, 2006.

Detail of Hotei

Comments: “Hotei, a popular figure in the Zen pantheon, is often depicted as a rotund, good-humored monk carrying a large sack. A semihistorical figure, he is believed to have lived in southern China in the late ninth century and was eventually recognized as a manifestation of Miroku (Sanskrit: Maitreya), Buddha of the Future. The poetic text, from a eulogy for Hotei by the Chinese Daoist Bai Yuchan (1194–1229), was transcribed by Tetsuzan Sōdon, a leading Zen monk-scholar who served as an abbot of the Myōshinji Temple in Kyoto”.

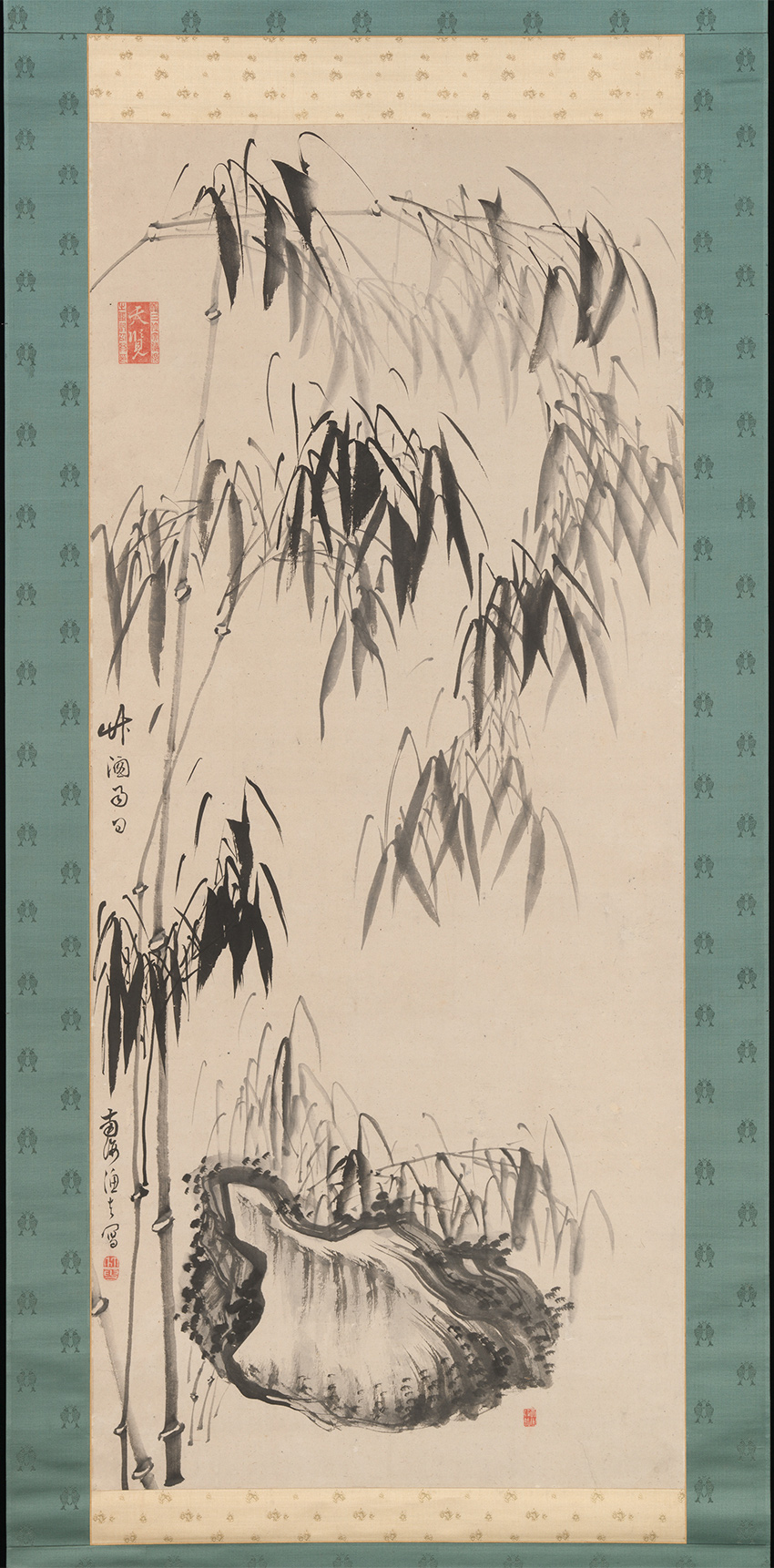

祇園南海筆 「竹窗雨日」図

Window onto Bamboo on a Rainy Dayfirst

half of the 18th century

Window onto Bamboo on a Rainy Day, by Gion Nankai (Japanese, 1677–1751). Edo period (1615–1868). First half of the 18th century. Hanging scroll; ink on paper, 52 5/8 × 22 13/16 in. (133.7 × 58 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke.

Window onto Bamboo on a Rainy Day, by Gion Nankai (Japanese, 1677–1751). Edo period (1615–1868). First half of the 18th century. Hanging scroll; ink on paper, 52 5/8 × 22 13/16 in. (133.7 × 58 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke.

尾形乾山筆 定家詠十二ヶ月和歌 花鳥図 『拾遺愚草』 より六月

“Fourth Month” from Fujiwara no Teika’s

“Birds and Flowers of the Twelve Months”, 1743

“Sixth Month” from Fujiwara no Teika’s “Birds and Flowers of the Twelve Months”, 1743, by Ogata Kenzan (Japanese, 1663–1743). Edo period (1615–1868). Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper, image: 6 1/4 x 9 1/8 in. (15.9 x 23.2 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Comments: “Kenzan, brother of the painter and designer Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716), is best known as a potter, but he was also a gifted painter and calligrapher. The poems were taken from the Shūigusō (Gleaning of Worthless Weeds), a collection of verse by the influential poet and calligrapher Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241). The poems from the fourth month refer to unohana (deutzia flowers) and to the hototogisu, a bird related to the cuckoo. They read: Shirotae no / koromo hosu chō / nasu no kite / kakine mo tawa ni / sakeru u no hana / / Hototogisu / Shinobu no sato ni / sato nare yo / mada u no hana no / tsuki matsu goro / / Robes of white cloth / should be aired out, they say, / just when summer arrives / and deutzia flowers in bloom / cause the hedge to droop. / / In the village of Shinobu / where the cuckoo dwells, / its cry is now heard, / while we await next month / when deutzia flowers bloom”.

S C U L P T U R E S

男神坐像

Shinto Deity as a Seated Courtier

11th–12th century

Shinto Deity as a Seated Courtier, 11th–12th century, Heian period (794–1185). Wood; single-block (ichiboku-zukuri) construction, with traces of red and black pigment, H. 18 in. (45.7 cm); W. 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm); D. 5 in. (12.7 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2015.

Shinto Deity as a Seated Courtier, 11th–12th century, Heian period (794–1185). Wood; single-block (ichiboku-zukuri) construction, with traces of red and black pigment, H. 18 in. (45.7 cm); W. 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm); D. 5 in. (12.7 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2015.

Comments: “This figure, carved from a single piece of wood, represents a Shinto deity (kami) in the form of a Heian-period courtier. Around this time, divinity was conferred on the imperial court such that certain aristocrats, once deceased, were deified and venerated as kami. Some of them were responsible for the safety and stability of important clans. Despite the figure’s insect damage (common in Shinto statues from this period), its exposed wood grain—centered on the face—gives the work a dramatic effect”.

四天王立像

Guardian King of the Four Directions

12th century

Guardian King of the Four Directions, 12th century. Heian period (794–1185). Wood with traces of color, 33 in. (83.8 cm); W. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm); D. 8 1/16 in. (20.5 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Guardian King of the Four Directions, 12th century. Heian period (794–1185). Wood with traces of color, 33 in. (83.8 cm); W. 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm); D. 8 1/16 in. (20.5 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Comments: “This pair of statues, which flank the Cosmic Buddha Dainichi Nyorai, are from a set of four. Originally Hindu demigods, the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions, or Shitennō, were absorbed into the Buddhist pantheon as protectors of Buddhist teachings, the temple, and the nation. In China, such statues were usually positioned near temple entrances, but in Japan they more often surrounded the central deity on the main altar. These ferocious figures nearly always wear armor, carry weapons or other attributes (now lost), and stand in dynamic poses rather than static postures of ease or meditation. Each carved from a single block of wood, their muscular forms retain the strength of early Heian-period style. Only the arms, now missing, were carved separately”.

C E R A M I C S

三代高橋道八作 色絵桜楓文大鉢

Large Bowl with Cherry Blossoms and Maple Leaves

first half of the 19th century

Large Bowl with Cherry Blossoms and Maple Leaves, by Takahashi Dōhachi III (Japanese, 1811–1879).first half of the 19th century. Edo period (1615–1868).Stoneware with underglaze iron, white slip, and polychrome overglaze enamels (Kyoto ware), Diam. 22 7/16 in. (57 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2019.

Large Bowl with Cherry Blossoms and Maple Leaves, by Takahashi Dōhachi III (Japanese, 1811–1879).first half of the 19th century. Edo period (1615–1868).Stoneware with underglaze iron, white slip, and polychrome overglaze enamels (Kyoto ware), Diam. 22 7/16 in. (57 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2019.

Comments: “The combination of cherry blossoms and colorful maple leaves on this large bowl revive the style of Kyoto’s famous ceramic artist Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743). The vivid composition is based on a poem about the Tatsuta River, from the waka anthology Kokin Wakashū (ca. 905). The poet describes fallen autumn foliage drifting on the water’s surface as if it were gold brocade, and cherry blossoms in the Yoshino hills that put him in mind of white snowflakes. The patterns evoke both symbolic images of spring and autumn, as well as two famous sites (meisho) in Japan”.

清水六兵衛作 御本写立鶴文茶碗

Gohon (Korean-Style) Tea Bowl with Cranes

second half of the 18th century

Gohon (Korean-Style) Tea Bowl with Cranes, second half of the 18th century, by Kiyomizu Rokubei I (Japanese, 1737–1799). Edo period (1615–1868) Stoneware with white-slip inlay, underglaze iron, and red and white slip under transparent glaze (Kyoto ware, Kiyomizu type), H. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm); Diam. of rim 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); Diam. of foot 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm). The Howard Mansfield Collection, Gift of Howard Mansfield, 1936.

Gohon (Korean-Style) Tea Bowl with Cranes, second half of the 18th century, by Kiyomizu Rokubei I (Japanese, 1737–1799). Edo period (1615–1868) Stoneware with white-slip inlay, underglaze iron, and red and white slip under transparent glaze (Kyoto ware, Kiyomizu type), H. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm); Diam. of rim 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); Diam. of foot 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm). The Howard Mansfield Collection, Gift of Howard Mansfield, 1936.

永樂得全作 金襴手龍吉祥文鉢

Bowl with Dragons and Auspicious Motifs

second half of the 19th century

Bowl with Dragons and Auspicious Motifs, second half of the 19th century, by Eiraku Tokuzen (Japanese, 1853–1909). Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under and red and gold over a transparent glaze (Kyoto ware, Eiraku type). H. 3 1/8 in. (7.9 cm); Diam. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). Gift of Mrs. V. Everit Macy, 1923.

Bowl with Dragons and Auspicious Motifs, second half of the 19th century, by Eiraku Tokuzen (Japanese, 1853–1909). Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under and red and gold over a transparent glaze (Kyoto ware, Eiraku type). H. 3 1/8 in. (7.9 cm); Diam. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). Gift of Mrs. V. Everit Macy, 1923.

L A C Q U E R S

根来塗 瓶子 二口一対

Sake vessel (Heishi)

late 16th century

Sake vessel (Heishi), late 16th century. Muromachi period (1392–1573) Wood with black and red lacquer layers (Negoro ware). H. 14 1/8 in. (35.9 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2019.

Sake vessel (Heishi), late 16th century. Muromachi period (1392–1573) Wood with black and red lacquer layers (Negoro ware). H. 14 1/8 in. (35.9 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2019.

Comments: “Ritual sake bottles, made in pairs, were used in Shinto shrines for offerings to the kami. Most of these sake vessels are Negoro lacquers associated with the Negoro-dera Temple in Wakayama Prefecture. Turned on a lathe in pieces and then assembled, each is set on an upright, splayed base and features a tapered body, rounded shoulders, and neck rising to a rounded lip. A black-lacquer underlayer shows through the red outer layer in random patches due to use”.

千鳥松蒔絵香合

Incense Box (Kogo) with Pines and Plovers

early 14th century

Incense Box (Kogo) with Pines and Plovers, early 14th century. Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Lacquered wood with gold togidashimaki-e on nashiji (“pear-skin” ground). H. 1 1/2 in. (3.9 cm); W. 2 3/4 in. (6.9 cm); D. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm) Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

Incense Box (Kogo) with Pines and Plovers, early 14th century. Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Lacquered wood with gold togidashimaki-e on nashiji (“pear-skin” ground). H. 1 1/2 in. (3.9 cm); W. 2 3/4 in. (6.9 cm); D. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm) Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

Incense Box opened

Comments: “Like many other tea-ceremony incense boxes, this work might have originally been part of a twelve-piece cosmetic box set (jūnitebako), where it would have served as a container for tooth-blackening material. This meticulously crafted small box is decorated with an auspicious composition of plovers and evergreen pine trees on a seashore scattered with shells. Plovers are associated with longevity because their cry, chiyo, is a homonym for “a thousand years.”

菊桐紋蒔絵提子

Sake Ewer (Hisage)

with Chrysanthemums and Paulownia Crests in Alternating Fields

early 17th century

Sake Ewer (Hisage) with Chrysanthemums and Paulownia Crests in Alternating Fields, early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Lacquered wood with gold hiramaki-e and e-nashiji (“pear-skin picture”) on black ground, H. (incl. handle) 10 in. (25.4 cm); Diam. 7 in. (17.8 cm); W. (including spout) 10 1/8 in. (25.7 cm). Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange, 1980.

Sake Ewer (Hisage) with Chrysanthemums and Paulownia Crests in Alternating Fields, early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Lacquered wood with gold hiramaki-e and e-nashiji (“pear-skin picture”) on black ground, H. (incl. handle) 10 in. (25.4 cm); Diam. 7 in. (17.8 cm); W. (including spout) 10 1/8 in. (25.7 cm). Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange, 1980.

Comments: “The Kōdaiji style was the most prominent development in the history of Momoyama-period lacquer art, and is characterized by bold, large-scale patterns, autumn grass motifs, and crests executed in gold hiramaki-e (“flat sprinkled picture”) on a black ground. Patronage and construction of the temple for which the style is named are associated with Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his wife Nene (Kōdai-in, 1548–1624), and with shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), who generously supported the creation of the temple precinct and mausoleum in 1605 in honor of his opponent Hideyoshi. The application of the flat maki-e and large repetitive patterns made it possible to decorate everyday household objects with gold designs. Hideyoshi used this style to represent his political power and authority”.

桐唐草蒔絵阿古陀香炉

Melon-Shaped Incense Burner (Akoda Kōro)

with Paulownia and Foliage Scroll

early 17th century

Melon-Shaped Incense Burner (Akoda Kōro) with Paulownia and Foliage Scroll, early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Lacquered wood with gold hiramaki-e and e-nashiji (“pear-skin picture”) on black ground. H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm); Diam. 4 3/8 in. (11.1 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015.

根来塗 輪花盆

Flower-Shaped Tray (Rinka-bon)

15th century

Flower-Shaped Tray (Rinka-bon), 15th century. Muromachi period (1392–1573). Wood with black and red lacquer layers (Negoro ware), H. 5 1/4 in. (13.3 cm); Diam. 21 7/16 in. (54.5 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015.

Flower-Shaped Tray (Rinka-bon), 15th century. Muromachi period (1392–1573). Wood with black and red lacquer layers (Negoro ware), H. 5 1/4 in. (13.3 cm); Diam. 21 7/16 in. (54.5 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015.

C O S T U M E S

v胴箔地牡丹鳳凰模様縫箔

Noh Costume (Nuihaku) with Phoenixes and Peonies

second half 18th century

Noh Costume (Nuihaku) with Phoenixes and Peonies, second half 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Plain-waive silk with gold leaf and silk-thread embroidery, 62 x 52 in. (157.5 x 132.1 cm). Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1932.

Noh Costume (Nuihaku) with Phoenixes and Peonies, second half 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Plain-waive silk with gold leaf and silk-thread embroidery, 62 x 52 in. (157.5 x 132.1 cm). Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1932.

Detail of Noh Costume (Nuihaku) with Phoenixes and Peonies

Comments: “Nuihaku robes are elegant Noh costumes with very fine embroidery applied on a metal-leaf ground. Mainly used in plays featuring young female protagonists, they are worn around the waist beneath sumptuous outer robes. In the Momoyama (1573–1615) and early Edo periods, before outer robes became lavish garments, nuihaku were the most splendid part of the costume and were themselves used as outer robes. This exquisite example in the “phoenix flying through peonies” pattern is embellished with phoenixes, auspicious symbols of prosperity, fidelity, and good deeds as well as with peonies, the “king of flowers,” representing good fortune and honor. The composition is based on a design created by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795), a prolific Kyoto-based painter whose style incorporated Western naturalism into East Asian painting traditions”.

V胴箔地薄菊紅葉蝶模様縫箔

Noh Robe (Nuihaku) with Butterflies, Chrysanthemums,

Maple Leaves, and Miscanthus Grass

second half of the 18th century

Noh Robe (Nuihaku) with Butterflies, Chrysanthemums, Maple Leaves, and Miscanthus Grass, second half of the 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Silk satin with silk embroidery and gold leaf, 63 3/4 x 54 in. (161.9 x 137.2 cm). Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1932.

Noh Robe (Nuihaku) with Butterflies, Chrysanthemums, Maple Leaves, and Miscanthus Grass, second half of the 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Silk satin with silk embroidery and gold leaf, 63 3/4 x 54 in. (161.9 x 137.2 cm). Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1932.

Detail of Noh Robe (Nuihaku) with Butterflies,

Chrysanthemums, Maple Leaves, and Miscanthus Grass

Comments: “The butterfly motif came into its own in China during the Tang dynasty (618-906), and several examples of decorative arts of the Tang bearing this pattern were preserved in the eighth-century Shôsôin imperial repository in Nara, Japan. Chinese secular poetry and writings on Buddhism also featured the butterfly, and Japanese admiration for these texts helped bring the motif to the fore in the literary and visual arts of Japan, where its popularity has lasted for centuries. This robe is decorated only at the shoulders (kata) and hem (suso), where the embroidered autumn design is on a glowing background of gold leaf”.

祇園南海筆 白繻子地墨竹図打掛

Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo

first half of the 18th century

Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo, first half of the 18th century, by Gion Nankai (Japanese, 1677–1751). Edo period (1615–1868). Ink and gold powder on silk satin, 64 3/4 x 48 7/8 in. (164.5 x 124.2 cm) Sleeve length: 37 3/4 in. (95.9 cm); sleeve width: 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo, first half of the 18th century, by Gion Nankai (Japanese, 1677–1751). Edo period (1615–1868). Ink and gold powder on silk satin, 64 3/4 x 48 7/8 in. (164.5 x 124.2 cm) Sleeve length: 37 3/4 in. (95.9 cm); sleeve width: 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Detail of Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo

Comments: “This rare uchikake is the work of Gion Nankai, a well-known poet and painter of the early Nanga (Literati) movement, which had roots in Chinese painting traditions and Confucian studies. Bamboo, vividly painted here in light and dark ink enhanced with a mist of gold powder, was a favored subject of Nanga artists who were largely based in the Kyoto area. Karakane Kōryū (1675–1738), a merchant and literary scholar from Izumi Sano (present- day Osaka), commissioned this over robe for one of his concubines; it was thereafter treasured as a family heirloom. In 1824, on the occasion of the marriage of one of Kōryū’s great-granddaughters, the literati poet Rai San’yō (1780–1832) wrote a laudatory kanshi (a poem written entirely in Chinese characters) about the unsigned garment, thereby establishing its provenance”.

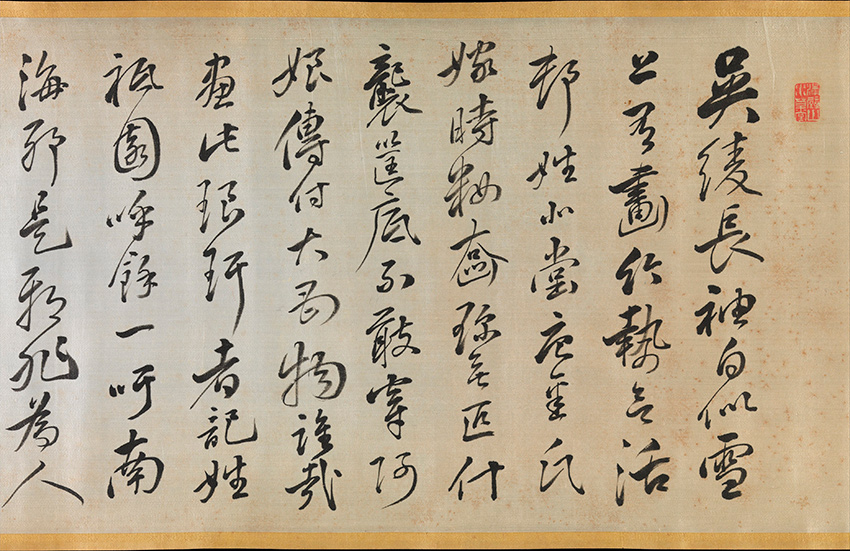

C A L L I G R A P H Y

頼山陽書 祇園南海筆墨竹図打掛に於いて

Poem Accompanying an Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo

by Gion Nankai (1677–1751) dated 1824

Poem Accompanying an Over Robe (Uchikake) with Bamboo by Gion Nankai (1677–1751), dated 1824, Edo period (1615–1868). Artist Rai San’yō (Japanese, 1781–1832). Artist: Rai San’yō (Japanese, 1781–1832). Handscroll; ink on silk, 11 7/8 x 116 3/4 in. (30.2 x 296.5 cm). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.

Comments: “The Confucian scholar, Nanga-school artist, and poet Rai San’yō was born in Osaka and studied in Hiroshima and Edo before decamping to Kyoto in 1811, where he opened a school and devoted himself to the writing of kanshi poetry (verses composed in Chinese by Japanese authors). This example was commissioned by the owners of a rare silk-satin over robe with a bamboo forest painted in ink by the renowned Nanga artist Gion Nankai (displayed nearby). The garment had been treasured for generations by the Karakane family, and the poem, in expertly and crisply brushed Chinese characters, was intended to celebrate its inclusion in the trousseau of a young Karakane woman”.

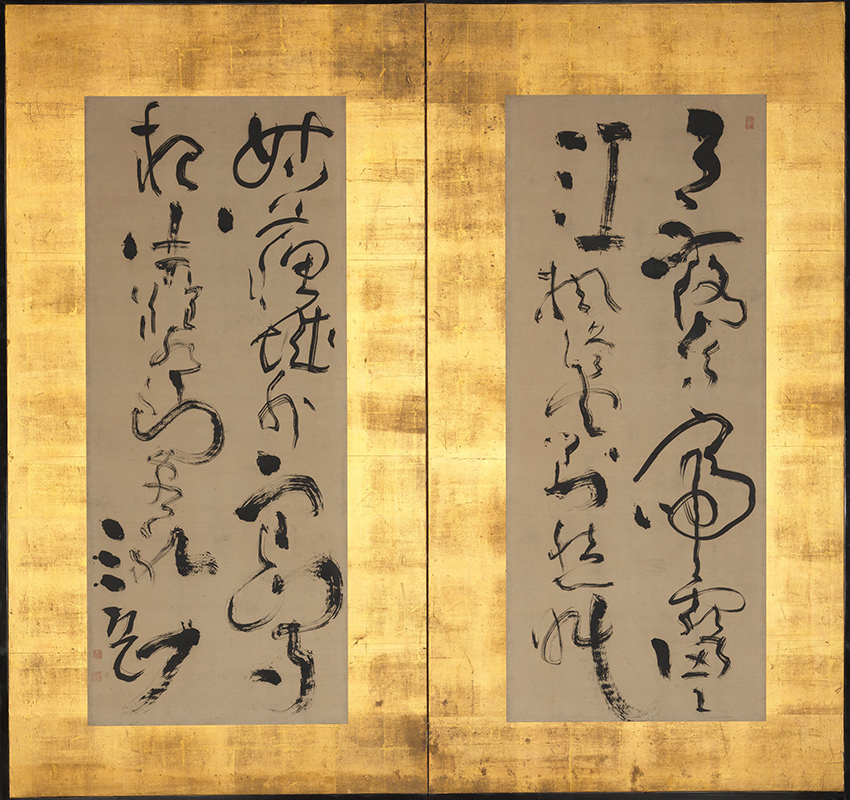

池大雅書 「楓橋夜泊」屏風

“Maple Bridge Night Mooring”

ca. 1770

“Maple Bridge Night Mooring”, ca. 1770, by Ike Taiga (Japanese, 1723–1776). Edo period (1615–1868). Two-panel folding screen; ink on paper, image (each panel): 53 1/4 x 22 1/8 in. (135.3 x 56.2 cm), Overall: 68 3/4 x 72 3/4 in. (174.6 x 184.8 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2008.

“Maple Bridge Night Mooring”, ca. 1770, by Ike Taiga (Japanese, 1723–1776). Edo period (1615–1868). Two-panel folding screen; ink on paper, image (each panel): 53 1/4 x 22 1/8 in. (135.3 x 56.2 cm), Overall: 68 3/4 x 72 3/4 in. (174.6 x 184.8 cm). Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2008.

A B O U T K Y O T O

Heian-kyō, as modern-day Kyoto was once referred to, became the seat of the imperial court in 794 and remained the capital of Japan until 1869, when the court was transferred to Tokyo. The rich cultural heritage of this city was profoundly shaped by the presence of the emperor and aristocrats as well as high-ranking warriors, varied groups of artists, and literati working in the orbit of the palace. Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, Noh theaters, workshops of painters and lacquer artists, ceramic kilns, textile shops, a flourishing tea culture, and bustling market districts, as well as supremely elegant architecture and gardens contributed to the advancement of the vibrant cultural life of Kyoto.

The exhibition is made possible by The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation Fund

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10028 Phone: 212-535-7710

https://www.metmuseum.org/