POWER AND BEAUTY IN CHINA’S LAST DINASTY

February 3 through May 27, 2018

The MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART

Imperial Throne, Qianlong period (1736–1795) China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Polychrome lacquer over a softwood frame. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 93.32a-d

Imperial Throne, Qianlong period (1736–1795) China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Polychrome lacquer over a softwood frame. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 93.32a-d

Famous theater director and visual artist Robert Wilson has created an immersive

and experiential environment to showcase the famous Chinese art collection of the

Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) Scenographies and effective uses of light on works of art

show the opulence of the Qing Empire, the last imperial dynasty of China.

Exhibition Experience

The exhibition shows through ten galleries from the outer world of the imperial court to the emperor’s inner and intimate world. Each gallery also features sound effects created in collaboration with sound designer Rodrigo Gava, and dramatic lighting by designer A. J. Weissbard.

Gallery 1 – Darkness

Power and Beauty begins in a dark room containing a single, illuminated object: a black glazed porcelain vase, manufactured at the royal Qing kiln. In ancient Chinese philosophy, darkness is considered complementary to brightness. Light and dark are physical manifestations of yin and yang, the duality at the heart of most classical Chinese science and philosophy.

Power and Beauty begins in a dark room containing a single, illuminated object: a black glazed porcelain vase, manufactured at the royal Qing kiln. In ancient Chinese philosophy, darkness is considered complementary to brightness. Light and dark are physical manifestations of yin and yang, the duality at the heart of most classical Chinese science and philosophy.

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Bottle Vase, 19th century. Porcelain

Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 96.97.16

Gallery 2 – Prosperity

Emptiness gives way to abundance and dark gives way to light to create an immediate and heady contrast. In this gallery, a display of more than wo hundred works in various media conjures the emperors’ insatiable appetite for art. At the empire’s peak in the 1700s, there was unprecedented prosperity and political stability, which allowed the decorative arts to flourish. The Forbidden City in Beijing, where the emperor’s court was based, became a center of artistic production, and the emperors commissioned workshops to create opulent objects for their palaces. A joyful song from Puccini’s opera Turandot, which is set in China, serves as the soundscape, further strengthening the festival-like atmosphere of the gallery.

Gallery 3 – Order and Hierarchy

A rigid social hierarchy—with an omnipotent emperor who answered only to the heavens above—ensured the stability of the empire. This hierarchy was rigidly enforced by a strict dress code, which denoted a noble’s title, rank, and social status through color, symbolism, and accessories. In the center of the gallery, eight imperial robes are arrayed by rank. Only the highest-ranking members of the royal family could wear robes decorated with the 12 imperial symbols: the sun, moon, mountain, constellations, dragon, axe, cups, flame, bat, grain, pheasant, and waterweed.

Only the emperor himself could wear yellow

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Manchu Emperor’s Ceremonial Twelve-symbol jifu Court Robe, 1723–1735, Silk tapestry (kesi) The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.11

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Manchu Emperor’s Ceremonial Twelve-symbol jifu Court Robe, 1723–1735, Silk tapestry (kesi) The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.11

In addition to the rigid display of dragon robes, the grey carpet and the sound of wood blocks striking underline the rigid and severe imperial bureaucratic system. Straw thatch mounted on the walls, which evokes the lower classes the emperor ruled, serves as a foil to the delicacy and exquisiteness of the silk.

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Manchu Man’s Formal Court Robe, Daoguang period (1821–1850) Embroidered satin, The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.63

Gallery 4 – The Common Man

This gallery forms the core of the exhibition. Within a space of equal size to the previous few galleries, a single object, a tiny bronze human figure from the 5th to 4th century BCE, is on view. Cast in fine detail, the figure stands formally posed with arms held out and fingers curled to form a socket, which would have held the shank of an object. The single human figure from China’s Bronze Age suggests the ancient Chinese philosophy of governance. The right to rule was divinely granted, but if an emperor was cruel and oppressive, it was said that he would lose the Mandate and be toppled. Alone in the center of a gallery with emerald green walls and a soundscape of the pure and innocent voice of a child singing, the bronze figure from around the time of Confucius faces the formidable imperial authority represented in the adjacent gallery.

This gallery forms the core of the exhibition. Within a space of equal size to the previous few galleries, a single object, a tiny bronze human figure from the 5th to 4th century BCE, is on view. Cast in fine detail, the figure stands formally posed with arms held out and fingers curled to form a socket, which would have held the shank of an object. The single human figure from China’s Bronze Age suggests the ancient Chinese philosophy of governance. The right to rule was divinely granted, but if an emperor was cruel and oppressive, it was said that he would lose the Mandate and be toppled. Alone in the center of a gallery with emerald green walls and a soundscape of the pure and innocent voice of a child singing, the bronze figure from around the time of Confucius faces the formidable imperial authority represented in the adjacent gallery.

China, Warring States period

(575–221 BCE)

Standing Figure,

5th–4th centuries BCE

Bronze with gold inlay

Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

2003.140.3

Gallery 5 – Fearsome Authority

The emperor’s imperial throne conveys his fearsome authority. Gold lacquer dragons adorn the seat. Scrolls are carved into the sides, back, and legs, suggesting clouds and the emperor’s heavenly mandate to rule.

The emperor’s imperial throne conveys his fearsome authority. Gold lacquer dragons adorn the seat. Scrolls are carved into the sides, back, and legs, suggesting clouds and the emperor’s heavenly mandate to rule.

The Chinese believe that China was at the center of the world. The throne embodies this concept. It was in fact was at the center of the Forbidden City in a Throne Hall elevated about 26 feet above the surrounding square.

Placed there, it was as though the emperor could survey his entire kingdom. The soundscape of ceremonial music is intermittently interrupted by a hair-raising scream.

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Imperial Throne, Qianlong period (1736–1795) Polychrome lacquer over a softwood frame. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 93.32a-d

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Imperial Throne, Qianlong period (1736–1795) Polychrome lacquer over a softwood frame. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 93.32a-d

Gallery 6 – Buddhist Art

Amid the chants of a Buddhist sutra (scripture), five Buddhist statues stand on high pedestals, demanding visitors look up to see them. Religion and politics were often intertwined as rulers engaged in religious devotion and patronage of the religious arts in order to reinforce their reign. Buddhism was a major catalyst for monumental sculpture, painting, printing, and architecture. The Buddhist monk Faguo expressed this link in the early fifth century when he equated the emperor with the Buddha, explaining, “the Buddhist law would be very difficult to disseminate if it did not rely on imperial power and influence.”

LEFT: China, Tang dynasty (618–907) The Monk Ananda, 9th century. Limestone. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 98.166RIGHT: China, Northern Qi dynasty (550–577) Standing Buddha, late 6th century, Limestone. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 2000.207

LEFT: China, Tang dynasty (618–907) The Monk Ananda, 9th century. Limestone. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 98.166RIGHT: China, Northern Qi dynasty (550–577) Standing Buddha, late 6th century, Limestone. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 2000.207

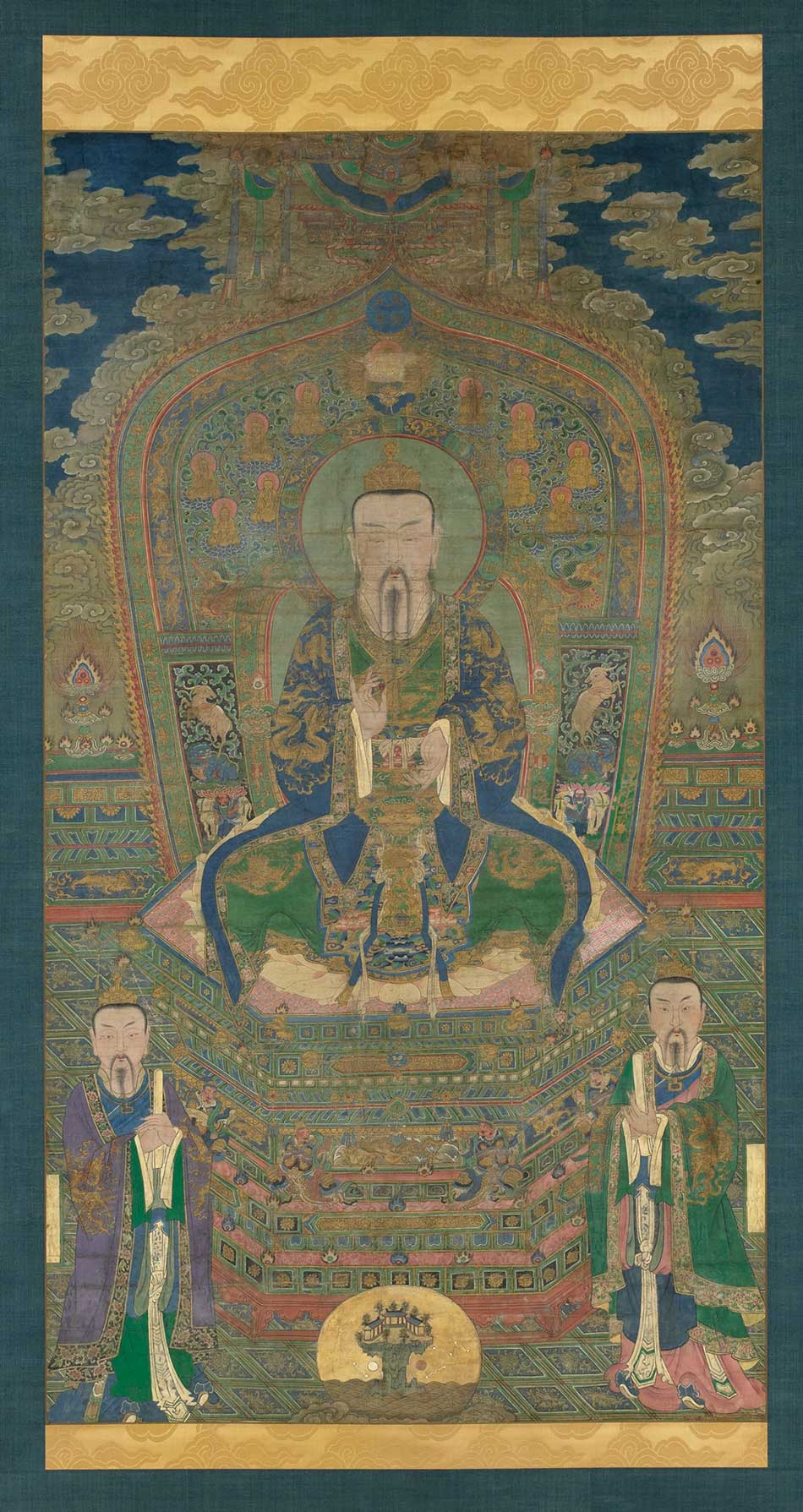

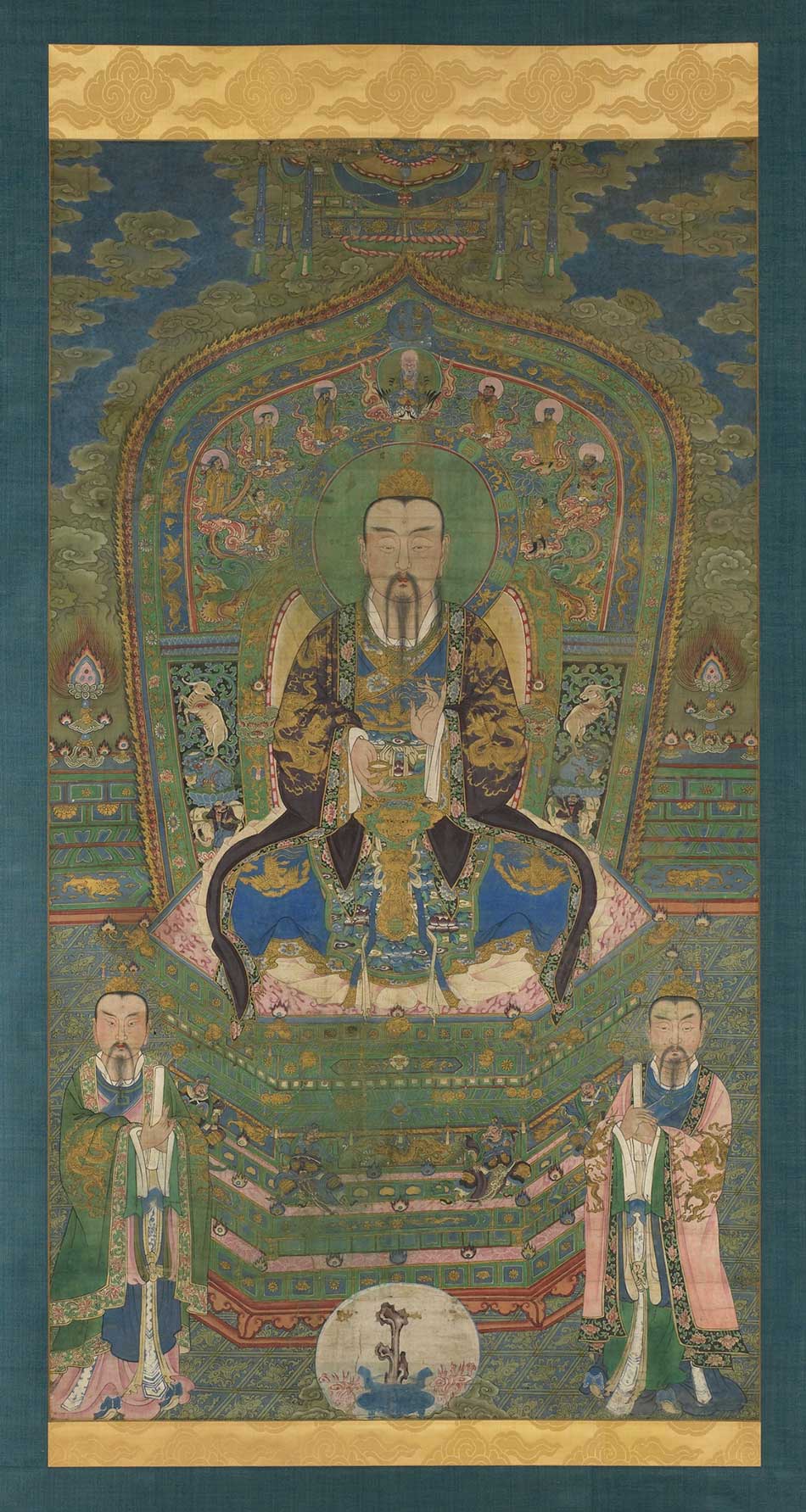

Gallery 7 – Daoist Art

A gallery devoted to Daoist paintings, accompanied by the sounds of Daoist texts being read. During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Daoism flourished alongside Buddhism. Its roots can be traced to the sage Laozi (c. 571 BCE–c. 471 BCE), who wrote the classic text Daodejing (The Way and Its Power). Six centuries later, Daoism emerged as an organized religion with a supreme god known as Tianzun (Heavenly Worthy), a canon of scriptures, temples, priests, and a practice modeled on traditional Chinese popular religion. Its influence extended to Chinese art and culture, and, like Buddhist art, was used by rulers to legitimize their rule. The walls and the floor are covered with earthen plaster.

The Three Purities

Late 16th century Ink, colors, and gold on silk.

China, Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

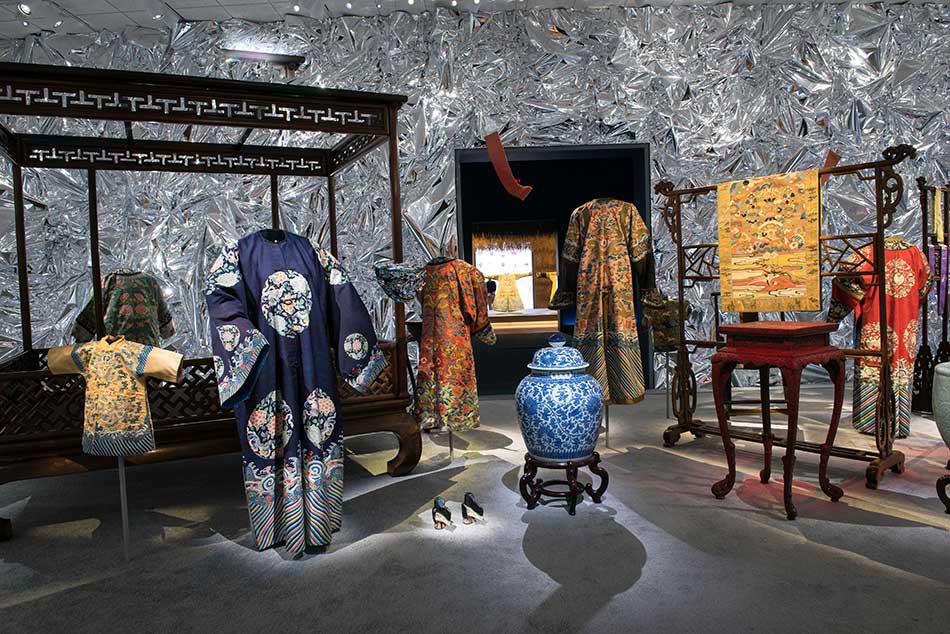

Gallery 8 – Court Ladies and Noble Women

In male-dominated Chinese imperial society, and within the principle of yin and yang, women were considered the counterpoint to men—existing only in relation to them. In this gallery, objects associated with noblewomen suggest the palace’s inner quarters. The Qing period saw unparalleled production of gold and silver jewelry and the development of sophisticated technology for clothing manufacture, creating a remarkable material culture of garments and adornments for noblewomen. Placed irregularly, works in different media with different functions are juxtaposed. The aluminum-foil wallpaper suggests a voluptuous and extravagant lifestyle, but the soundscape, which is a melody with bitter and sad tones performed on an erhu (a two-stringed instrument) counterpointed by a woman giggling intermittently, conveys the life and destiny of Chinese women in the imperial period.

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Empress Formal Court Robe, Daoguang period (1821–1850) Silk tapestry (kesi)

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Empress Formal Court Robe, Daoguang period (1821–1850) Silk tapestry (kesi)

The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.72

Gallery 9 – Mountains of the Mind

A display of two and three-dimensional depictions of mountain landscapes represents the ruler’s and scholar- officials’ fascination with nature. Steeped in centuries of religion, history, literature and folklore, China’s mountains are seen as divine realms and endowed with myriad sacred associations. Emperors and courtiers alike dreamed of retreating from society into a life of seclusion in the mountains—an escape that remained hypothetical. Instead, they cultivated the concept of chaoyin (“recluse at court”), a belief that one could engage with the world while preserving an internal sense of seclusion, remaining spiritually remote and uncontaminated by public life.

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Jade Mountain Illustrating the Gathering of Scholars at the Lanting Pavilion, Qianlong period, 1790. Light green jade. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and Gift of the Thomas Barlow Walker Foundation 92.103.13

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Jade Mountain Illustrating the Gathering of Scholars at the Lanting Pavilion, Qianlong period, 1790. Light green jade. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and Gift of the Thomas Barlow Walker Foundation 92.103.13

China, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) Pillow, 17th–18th century, Greenish-white nephrite. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and Gift of the Thomas Barlow Walker Foundation 92.103.8

China, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) Pillow, 17th–18th century, Greenish-white nephrite. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and Gift of the Thomas Barlow Walker Foundation 92.103.8

China, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) Pleasure boat, Qianlong period (1736-1795) Jade, 94.103.10a-f

China, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) Pleasure boat, Qianlong period (1736-1795) Jade, 94.103.10a-f

LEFT: China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Nine Dragon Box, Qianlong period (1736–1795) Red, green, and brown carved lacquer (ticai) Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 2001.68.14a,bRIGHT: China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Covered Vase in Mughul Style, Qianlong period (1736–1795) White camphor jade. Gift of Mr. Augustus L. Searle 37.56a,b

LEFT: China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Nine Dragon Box, Qianlong period (1736–1795) Red, green, and brown carved lacquer (ticai) Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 2001.68.14a,bRIGHT: China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Covered Vase in Mughul Style, Qianlong period (1736–1795) White camphor jade. Gift of Mr. Augustus L. Searle 37.56a,b

China, Qing dynasty, (1644–1911) Imperial Garniture, 1723–1735. Bronze. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 99.121.1.1-5

China, Qing dynasty, (1644–1911) Imperial Garniture, 1723–1735. Bronze. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 99.121.1.1-5

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Five Hundred Luohans, Qianlong period (1736–1795) K’ossu (silk brocade) with traces of pigment. The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.343

China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) Five Hundred Luohans, Qianlong period (1736–1795) K’ossu (silk brocade) with traces of pigment. The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.343

Statement

Matthew Welch

Mia’s Deputy Director and Chief Curator.

“Throughout the exhibition Robert Wilson strived to create a sense of duality, creating a series of juxtapositions throughout the exhibition,”

“Darkness gives way to brightness. Abundance yields to scarcity. The objects are cast, quite literally, in a new light.”

Statement

Liu Yang

Mia’s curator of Chinese Art and head of China, South, and Southeast Asian Art.

“Mia has one of the world’s great collections of Chinese art outside of China,”

“Our collection of Qing dynasty textiles is one of the most comprehensive in the West, and we have many other important objects associated with the Qing emperors and their courts. It is personally very exciting for me to be able to highlight these objects in an unexpected and fresh manner by working with Robert Wilson.”

Support

Presenting Sponsor: Sit Investment Associates

Lead Sponsor: Nivin and Duncan MacMillan Foundation

Major Sponsor: Delta Air Lines Inc.

Generous support provided by Gale Family Endowment

About the Asian Art Collection at Mia. Mia’s collection of Asian art comprises some 16,800 objects ranging from ancient pottery and bronzes to works by contemporary artists, with nearly every Asian culture represented. Areas of particular depth include the arts of China, Japan, and Korea.

Specific subsets and highlights of these collections rival the holdings of museums across the globe. The museum’s holdings of ancient textile, lacquer wares and hardwood furniture comprise one of the largest and best collections in the West. For its stylistic diversity and condition, Mia’s collection of ancient Chinese bronze is typically considered one of the nation’s top collections of its kind. Important examples include a famous vessel in the form of an owl, superb silver inlaid works, and many other outstanding vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (c. 17th–3rd century BCE). Mia’s Japanese collection has outstanding concentrations of Buddhist sculpture, woodblock prints, paintings, lacquer, works of bamboo, and ceramics, and is particularly rich in works from the Edo period (1610–1868).

All images courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

The MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART

2400 Third Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55404

888 642 2787 (Toll Free)

https://new.artsmia.org/