S A H E L

Art and Empire on the Shores of the Sahara

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, until 26 October 2020

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

From the first millennium, Africa’s western Sahel—a vast area on the

southern edge of the Sahara Desert, spanning what is today Senegal, Mali,

Mauritania, and Niger—was the birthplace of a succession of influential states

fueled by regional and global trade networks.

Is the first exhibition to trace the cultural legacy of the region,

including the legendary empires of

Ghana (300–1200),

Mali (1230–1600),

Songhay (1464–1591),

Segu (1640–1861)

The exhibition will bring together some 200 works that were created in parallel to these developments, including spectacular sculptures in wood, stone, fired clay, and bronze; gold and cast metal artifacts; woven and dyed textiles;

and illuminated manuscripts.

HIGHLIGHTS

Equestrian, Bura-Asinda-Sikka Site, Niger. 3rd–10th century

Equestrian. Bura-Asinda-Sikka Site, Niger. 3rd–10th century. Terracotta. H. 24 7/16 × W. 20 1/2 × D. 7 7/8 in. (62 × 52 × 20 cm) Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Niger (BRK 85 AC 5e5) Photo credit: © Photo Maurice Ascani.

Curator’s commentary: Horses were present in the southern Sahara (present-day Libya) by the first millennium B.C. The earliest physical evidence of horses in the Sahel ranges from a.d. 600 to 900. This rider, laden with bandoliers, necklaces, bracelets, and the elaborate harness and headdress of his mount, accompanied the burial of a high-ranking individual. Unearthed in a multitude of pieces, the work was reassembled. Man and horse are unified in a sinuous line, from the rider’s elongated arm to the horse’s dramatically attenuated muzzle.

Details of Equestrian. Bura-Asinda-Sikka Site

Equestrian, Dogon peoples. 16th-17th century

Equestrian. Dogon peoples, Mali. 16th–17th century. Wood and pigments. H. 31 7/8 × W. 14 × D. 7 in. (81 × 35.6 × 17.8 cm) Fondation Dapper, Paris (123) Photo credit: © Archives Fondation Dapper—Photo Hughes Dubois.

Curator’s commentary: In Dogon culture, the horse was understood metaphysically as the vehicle that carried humanity to and from the heavens. Riders are portrayed on sloping equine backs that raise them closer to the sky. The idea of a celestial journey that spans the physical and the immaterial is echoed in the expansive negative space framed by the horse’s body and legs.

Equestrian, Mali, Dogon peoples. 16th-18th century

Equestrian. Mali, Dogon peoples. 16th–18th century. Wood. H. 27 1/2 in. × W. 7 in. × D. 16 3/4 in. (69.9 × 17.8 × 42.5 cm.) The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

Curator’s commentary: From the time of the dissolution of the Mali empire, Dogon communities periodically found themselves fending off attacks from outside aggressors. While no Dogon cavalry existed to take on that role, this rider—equipped with a sheathed dagger and combatively raising a javelin (now missing)—is representative of the responsibility Dogon leadership held as spiritual and worldly defender.

Detail of Equestrian. Mali, Dogon peoples

Equestrian, Pendant: Mali, Dogon or Bozo peoples. 19th century

Equestrian. Mali, Dogon or Bozo peoples. 19th century. Copper alloy. H. 3 1/2 × W. 3 1/4 × D. 1/2 × L. 3 5/8 in. (8.9 × 8.3 × 1.3 × 9.2 cm) Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1975

Curator’s commentary: Functional and sacred metalwork and ceramics were produced and consumed across the Middle Niger. As blacksmiths mastered the manipulation of various metals, they developed ambitious imagery that paralleled examples in fired clay. Notable among these shared subjects was the equestrian figure. The small scale of this intimate cast creation suggests a talisman worn upon the body.

Details of Equestrian Pendant

Hand, Bura-Asinda-Sikka, Niger. 3rd–11th century

Hand. Bura-Asinda-Sikka, Niger . 3rd–11th century. Terracotta. H. 4 3/4 × W. 2 3/4 × D. 2 9/16 in. (12 × 7 × 6.5 cm) Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Niger (AC3 BRK 85) Photo credit: © Photo Maurice Ascani.

Curator’s commentary: Between the third and tenth centuries, the dead were laid to rest at a site in present-day Niger downstream from the Inland Niger delta. The burial ground’s density and expanse suggest a veritable city of the departed. Several hundred individual graves were marked by upturned pottery urns, some of which were cylinders topped by figurative imagery. The most elaborate of these were full-bodied equestrians, while the most basic were highly abstract, independent heads.

Reclining Figure

Middle Niger civilization, Jenne-jeno, Mali. 12th–14th century

Reclining Figure Middle Niger civilization, Jenne-jeno, Mali 12th–14th century Terracotta. H. 10 5/8 × W. 14 3/16 × D. (est.) 9 in., 324.484 oz. (27 × 36 × 22.9 cm, 9.2 kg) Musée National du Mali, Bamako (R 88-19-275) Photo credit : Musée National du Mali

Curator’s commentary: Unearthed in an ancient refuse heap, this is the most imposing of the sculptures recovered at Jenne-jeno. The absence of its head perhaps resulted from an act of deliberate disfigurement prior to the work’s disposal. The androgynous figure’s elite status is reflected in its corpulent physique and elaborate accessories, while its reclining posture is alternately suggestive of consultation or leisure. This work may have been intended to assert indigenous beliefs at a time of social or political stress in Jenne-jeno.

Kneeling Female Figure with Crossed Arms

Middle Niger civilization, Mali. 12th–14th century

Kneeling Female Figure with Crossed Arms. Middle Niger civilization, Mali. 12th–14th century. Terracotta . H. 20 × W. 8 3/8 × D. 10 3/4 in. (50.8 × 21.3 × 27.3 cm) The Menil Collection, Houston (1982-20 DJ) Photo credit: Courtesy Menil Collection

Curator’s commentary: Middle Niger figurative representations feature a diverse cast of protagonists, from committed couples to the striking personage of a kneeling male. Many of these figures assume recumbent, prostrate, or upward-gazing postures. Gestures of arms crossed against the chest or covering the face suggest attitudes of prayer.

Figure with Raised Arms,

Tellem civilization.16th–17th century

Curator’s commentary:

Curator’s commentary:

The gesture of extending both arms above the head has been interpreted as an entreaty for rain. During the period in which this work was likely carved, rainfall in the Sahel is known to have significantly increased following a period of drought. The two-sided composition of this planar sculpture is powerful in silhouette and plays with subtle relief elements.

On the front, the abbreviated arms frame an oval projection of the head that aligns with traces of raised elements suggestive of the navel and female genitalia. Embedded within an otherwise blank expanse on the reverse is a human figure that echoes the work’s overall form in miniature.

Figure with Raised Arms.

Tellem civilization, Ibi, Mali.

16th–17th century .

Wood and organic materials.

H. 17 11/16 × W. 8 × D. 5 in.

(45 × 20.3 × 12.7 cm)

Fondation Dapper, Paris (0063)

Photo credit: © Archives Fondation Dapper—Photo Hughes Dubois

Figure Group

Mali, Soninke or Dogon peoples. 16th–19th century

Figure Group. Mali, Soninke or Dogon peoples. 16th–19th century. Wood. H. 16 3/4 x W. 5 x D. 2 3/4 in. (42.5 x 12.7 x 7 cm) Gift of Lester Wunderman, 1985

Curator’s commentary: The exodus of Soninke residents from centers such as Jenne-jeno by 1400 likely led some among them to resettle in the nearby Bandiagara plateau. That locale’s arid climate preserved wood sculpture, which was produced there as early as the tenth century. Some among these early wood artifacts formally resemble fired-clay and cast-metal artistic creations made in the Middle Niger valley.

Detail of Figure Group

Seated Male Figure

Mali, Dogom or Bozo peoples. 16th–17th century

Curator’s commentary: In order to forge staffs of office, Mande blacksmiths channeled esoteric expertise and the creative force of nyama. That process invested such signs of authority with the powers of invincibility and might, which were also directed toward the production of weaponry. The regal leader depicted at the summit of this staff holds an iron-pointed spear, an insignia of power and military superiority dating back to ancient Ghana.

Curator’s commentary: In order to forge staffs of office, Mande blacksmiths channeled esoteric expertise and the creative force of nyama. That process invested such signs of authority with the powers of invincibility and might, which were also directed toward the production of weaponry. The regal leader depicted at the summit of this staff holds an iron-pointed spear, an insignia of power and military superiority dating back to ancient Ghana.

Seated Male Figure.

Mali, Dogon or Bozo peoples.

16th–17th century. Copper alloy, iron.

H. 30 1/2 × W. 4 1/4 × D. 4 in.

(77.5 × 10.8 × 10.2 cm)

Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1975

Detail of Seated Male Figure

Female Figure with Raised Arm

Mali, Ireli (?) Tellem civilization (?) 15th–17th century

Female Figure with Raised Arm. Mali, Ireli (?) Tellem civilization (?)15th–17th century.Wood (Ficus or Moraceae), organic materials. H. 17 5/8 × W. 3 1/4 × D. 4 7/8 in. (44.8 × 8.3 × 12.4 cm) The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

Curator’s commentary: Later Dogon settlers who encountered Tellem works both appropriated the artifacts for their own altars and also took creative inspiration from them. The few examples of Tellem sculpture found undisturbed by researchers in the twentieth century range from highly abstract to naturalistic representations. Their distinctive gesture of raised arms has been interpreted as a prayer for rain. Such works accrued their thick organic surfaces over the course of successive applications of offerings such as millet porridge or the blood of sacrificial animals.

Mother and Child

Mali, Bamana peoples. 15th–early 20th century

Mother and Child. Mali, Bamana peoples. 15th–early 20th century. Wood. (Approx.) H. 46 1/2 × W. 14 × D. 14 in. (118.1 × 35.6 × 35.6 cm) Private collection. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo by Peter Zeray)

Curator’s commentary: In Bamana society, individuals can acquire mystical knowledge through initiation into a number of distinct associations. Induction into the Jo association followed a six-year course of study by all young men and some women. Jo’s leadership sponsored the creation of sculptures by Bamana blacksmiths that represented cultural ideals and values. The regal protagonists are defined by a crisp precision and idealized naturalism that exemplifies jayan, or aesthetic of clarity. The visual impact of the larger-than-life allegorical figures attracted the attention, focused the eye, and directed the thoughts of viewers who assembled to reflect collectively upon shared social ideals. A personification of motherhood, referred to as Gwandansu, was the centerpiece of such annually displayed sculptural ensembles, or tableaux vivants.

Details of Mother and Child

Horse or Chariot Ornament

Sincu Bara, Matam region, Senegal. 9th–12th century

Horse or Chariot Ornament. Sincu Bara, Matam region, Senegal. 9th–12th century. Bronze. H. 1/8 × Diam. 5 in. (0.3 × 12.7 cm) Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal (SEN.73.21.22) Photo credit: Photo by Antoine Tempé

Curator’s commentary: During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Silla and Takrur were the preeminent trade centers on the Senegal River for the export of gold and slaves. Silla, which researchers speculate may be the site of Sincu Bara, was a twenty-day march from its peer state Ghana, with a population that had converted to Islam and a king who was at war with his “pagan” neighbors. This artifact was found in Sincu Bara among other finely decorated artifacts cast in brass and copper, evidence of the vibrant craftsmanship and taste for luxury of the Middle Senegal valley at a time of expanding trans-Saharan exchange.

Pectoral (The Rao Pectoral)

Rao/Nguiguela, Senegal. 12th–13th century

Pectoral (The Rao Pectoral) Rao/Nguiguela, Senegal. 12th–13th century. Gold. Diam. 7 1/4 in. (5.1 × 18.4 cm)Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal (41 32) Photo credit: Photo by Antoine Tempé

Curator’s commentary: The exceptional quality and weight (6.7 ounces) of this pectoral make it the most impressive of the burial goods found at a site in northwest Senegal. Its decoration, elaborated in registers of bosses, arabesques, and diamond patterns made out of filigree, suggests an awareness of Islamic workmanship. The practice of erecting large mounds, or tumuli, over the graves of important individuals in the Sahel is related to commemorative practices and beliefs that preceded the arrival of Islam and continued well beyond its adoption into the fourteenth century.

Detail of The Rao Pectoral

Tunic. West Africa Before 1659

Tunic. West Africa Before 1659 Cotton and indigo. H. 50 13/16 × W. (top) 75 3/16 x W. (bottom) 38 3/16 in. (129 × 191 x 97 cm) Weickmann Collection, Museum Ulm, Germany (D.41) Photo credit: © Museum Ulm— Weickmann Collection, photo by Oleg Kuchar, Ulm.

Curator’s commentary: The fashion and design sensibility of the ancient textiles recovered from the Bandiagara caves is also found in several related tunics acquired in the seventeenth century by the wealthy Ulm merchant Christoph Weickmann. Among them is this spectacular royal robe, which was likely carried to the Atlantic coast via Mande trade networks and exported to Europe from the kingdom of Ardra by the mid-seventeenth century.

Boubou

Bamana peoples, Segu, Mali. Before 1879

Boubou. Bamana peoples, Segu, Mali. Before 1879. Cotton, silk, and dye. W. 76 9/16 × L. 51 3/16 in. (194.5 × 130 cm) Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris (71.1880.69.8) Photo credit : © Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Curator’s commentary: On a visit to Segu’s Sikoro market on November 11, 1878, French traveler Paul Soleillet admired the array of dozens of patterned fabrics on offer. He noted that “some are as fine as gauze, while others are strong and thick. Colors are very beautiful and include all nuances of blue, yellow, red and orange.” Although he purchased a number of boubous, wraps, and weaving samples that day, we have no specific information on this golden ensemble (together with the previous bonnet), which is a tour de force of the combined efforts of Middle Niger weavers, dyers, and embroiderers.

Detail of Boubou

Boli

Bamana peoples, Mali. 19th–20th century

Boli. Bamana peoples, Mali. 19th–20th century. Wood and sacrificial materials. H. 12 1/2 × W. 7 1/2 × D. 17 3/4 in. (31.8 × 19.1 × 45.1 cm) Collection of Francesco Pellizzi, New York. Photo credit: Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Peter Zeray.

Curator’s commentary: Segu’s leaders maintained political power through the possession and control of four potent occult objects known as “the great boliw of Segu.” Sometimes described as portable altars, boliw are understood to be a microcosm of the universe. Their surfaces are formed by packing, layering, and blending sacrificial materials into an indeterminate form that is believed to be a source of mystical power deliberately inaccessible to the uninitiated. Boliw were the primary targets of the jihad waged by the Umarian army. At the time of ‘Umar Tal’s victory over Segu, the leader’s chronicler Mamadou Ali Cam wrote:

The Differentiator [‘Umar Tal] then said to them [Bina Ali and the defeated Bamana]: “Now break them [the idols], crush them, and build mosques in all of Segu.” Ali said: “You mock me. You alone can smash them and survive. Anyone else would not live to tell the tale.” . . . Then the Unique One [‘Umar Tal] rose up and crushed [the idols] with his powerful hand, imitating the action of the Elected One [Muhammad] at Medina.”

Bala Mandinka peoples

Guinea or Mali 19th century

Bala Mandinka peoples, Guinea or Mali 19th century Wood, gourd, hide, and membrane. L. 34 1/16 x W. 17 15/16 × D. 8 11/16 in (86.5 x 45.5 × 22 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.492) Photo credit: Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Paul Lachenauer

Curator’s commentary: The bala is a xylophone with eleven to twenty hardwood slats tied to a bamboo frame. Suspended underneath each slat are hollow resonating gourds, arranged in graduated sizes. This early example is composed of fifteen gourd-resonated bars of wood that are struck by the musician with rubber-tipped mallets.

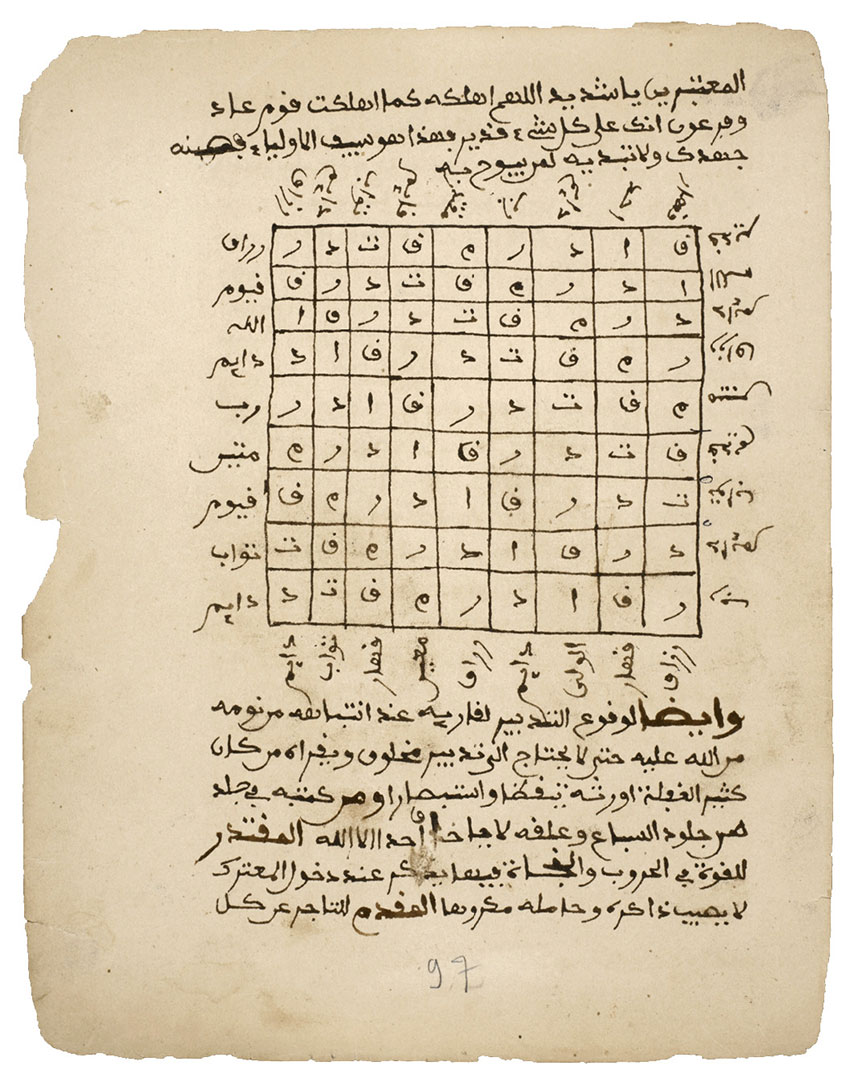

Curing Diseases and Effects both Apparent and Hidden

Timbuktu, Mali. 1733

Curing Diseases and Effects both Apparent and Hidden. Timbuktu, Mali. 1733. Manuscript on paper. H. 9 1/16 × W. 7 1/2 in. (23 × 19 cm) Mamma Haidara Memorial Library, Timbuktu, Mali (116) Photo credit: Mamma Haidara Memorial Library.

Curator’s commentary: This textual compilation of medicinal practices includes instructions for diagnoses and cures. The remedies described draw upon animal, plant, and mineral matter as well as prayers and Qur’anic verses. This page provides instructions for writing prayers to encase in amulets that would help the sick. A 2011 survey accounted for more than 100,000 such manuscripts preserved in no fewer than 408 private family libraries in Timbuktu and its surroundings.

Female Body (Venus of Thiaroye)

Senegal. Pre- 2000 B.C.

Female Body (Venus of Thiaroye) Senegal. Pre- 2000 B.C. Sandstone. W. 3/4 × D. 1 × L. 2 3/4 in. (1.9 × 2.5 × 7 cm) Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal. Photo credit: Photo by Antoine Tempé.

Curator’s commentary: The earliest societies to prosper in the Sahel were pastoralist communities. Their mobile elites accrued wealth and power in the form of cattle and semiprecious stones and memorialized themselves through the construction of tumuli—mounds for burials or the deposition of possessions. This delicately incised pebble, discovered casually in the vicinity of a dune, appears to have been imbued with symbolic meaning. Only minimal carving of the stone’s natural form was required to transform it into a tribute to procreation.

Megalith

Senegal, Kaolack region. 8th–9th century

Megalith, Senegal, Kaolack region. 8th–9th century. H. 82 11/16 × W. 63 × D. 31 1/2 in., 8862.5 lb. (210 × 160 × 80 cm, 4020 kg) Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal (IFAN)

Curator’s commentary: This rugged, carved megalith, distinctive for its lyrelike shape, was originally among more than one thousand stone monuments positioned in some ninety-three circles within a sixty-two mile band extending along the Gambia River. Four major concentrations of these have been found, including at the site of Wanar, which saw consistent if discontinuous occupation from the late second millennium B.C. until the twelfth century A.D. The creators of these enigmatic monuments were likely highly mobile herder farmers belonging to intermediate-scale communities. Their members may have periodically assembled at ritually specified times and been unified by a common regional identity.

A walk through the exhibition

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Installation view of Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2020, photography by Anna-Marie Kellen

Mali. Great Mosque of Djenné. The adoption of Islam in the Sahel in the 11th century as well as the impact of global trade across the region will be illustrated through precious documents, including an illuminated portolan map on vellum from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, produced in 1413 by the Majorcan cartographer Mecia de Viladestes.

CATALOGUE

Sahel

Sahel

Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara

Alisa LaGamma

9 × 11 in.

304 pages; 277 illustrations

ISBN: 978-1-58839-687-7

Hardcover, $65

With contributions from Yaëlle Biro, Mamadou Cissé, David C. Conrad, Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Roderick McIntosh, Paulo F. de Moraes Farias, Giulia Paoletti, and Ibrahima Thiaw.

This groundbreaking volume is the first book to present a comprehensive overview of the diverse cultural achievements and traditions of the African region known as the Sahel, a vast area on the southern edge of the Sahara desert that includes present-day Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad.

Essays by leading international scholars explore the unique cultural landscape in which these ancient communities flourished, spanning more than 1,300 years from the pre-Islamic period through the nineteenth century. Richly illustrated and brilliantly argued, Sahel brings to life the enduring creativity of the peoples who lived, traded, and traveled through this crossroads of the world.

Alisa LaGamma is Ceil and Michael E. Pulitzer Curator in Charge of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028, Phone: 212-535-7710

https://www.metmuseum.org/