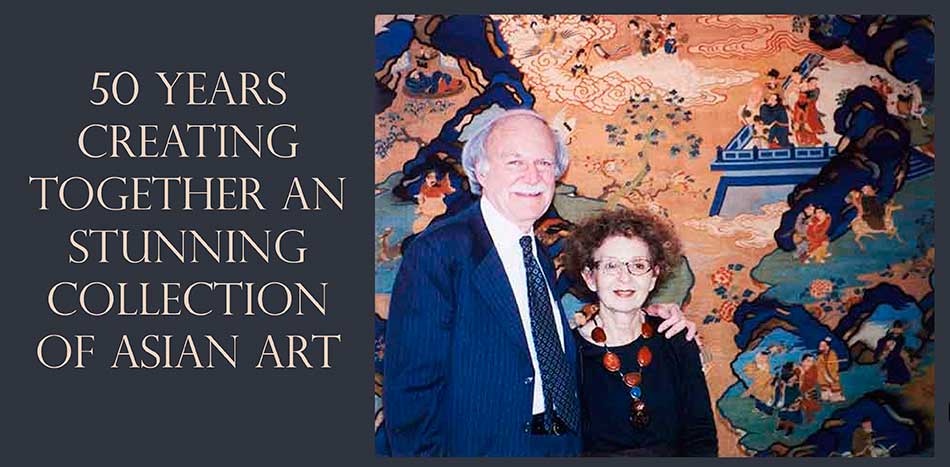

How they created their Collection

This is the story in the words of Sam and Myrna Myers

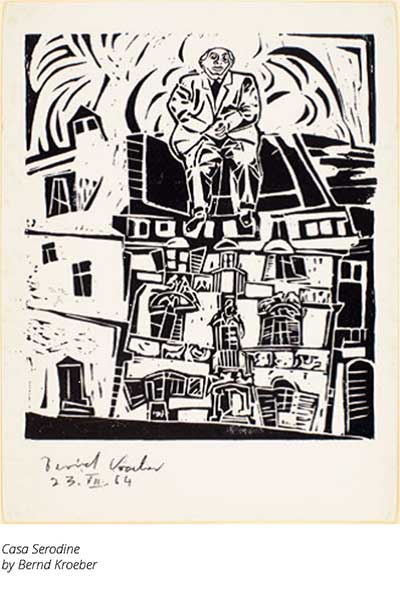

The Role of Chance. Recently married, Sam and Myrna Myers discovered antiques when they lived in New York. Moved to Paris they continued to visit antique dealers attracted by glass, ceramics, copper and carved wooden objects, nothing of importance. However, after their first year in Paris, they traveled on holiday to Switzerland, when chance intervened and opened a path they would follow for the rest of their lives… they discovered the antique shop “Casa Serodine” in Ascona.

1966 About this first experience Sam tells us…

On the main square, there was a magnificent four-story, heavily carved, 16th century building with a sign “Casa Serodine.” The great doors opened onto a large courtyard lined with glass cases filled with Greek, Roman, Persian and European objects, each with a label and number, but no prices. After a struggle to figure out whether it was an antique shop or a museum, we entered and were greeted by a lovely, young German woman, Barbara, who told us we could visit all four floors — which we did with avid excitement.

On the main square, there was a magnificent four-story, heavily carved, 16th century building with a sign “Casa Serodine.” The great doors opened onto a large courtyard lined with glass cases filled with Greek, Roman, Persian and European objects, each with a label and number, but no prices. After a struggle to figure out whether it was an antique shop or a museum, we entered and were greeted by a lovely, young German woman, Barbara, who told us we could visit all four floors — which we did with avid excitement.

When we finally came down, our heads spinning, Barbara asked if we would like to meet the owner, Dr. Rosenbaum. He was a very old man — small, round and bald — behind a desk in a room filled with objects. He rose, stretched out his hand and said, “Goodbye.” We later learned that that was his way of saying “Hello.” I told him we were astounded to see so many real antiques for sale, but that I, as a young lawyer, could not afford anything.

He peered over his glasses and asked, “Well, how much can you afford to spend?” I was flustered and said, “I don’t know. Maybe $20.” To our surprise he shouted, “Fritz, bring me the Tanagra heads.” Dr. Rosenbaum then turned to us saying, “You can choose any ones you want. $20.”

We couldn’t believe our ears. It was suddenly possible to have something real — a piece of history! With great excitement, we studied each piece and finally chose four small heads.

Return to Ascona for more discoveries.

Their determination to enter the world of collecting

The following year was our most important visit. We saw a black granite Egyptian head on the mantelpiece which captivated us. After going through the rest of the house, we told Dr. Rosenbaum we couldn’t get the sculpture out of our minds — though it was clearly out of our range. He suggested we think it over and that we talk again on Monday.

On Monday morning, we told him that we simply couldn’t stop thinking about the Egyptian head. He said he had been thinking too, and especially of the fact that we had a two-year old little girl, Caren.

He said, “You know, when you have a thing of beauty in the house, it creates an atmosphere, and that atmosphere affects the people that live there — that will affect Caren as she grows up. I think that if there is any way you can manage it, you should buy the sculpture.”

“But we can’t afford it.”

“How much can you pay every month, without missing

a month, till it’s paid for?”

After stumbling and stuttering, I blurted out, “I don’t know — $50?”

“O.K. But every month, and you can take the piece with you.”

In the years that followed in Ascona, and later in Israel, we concentrated on antiquities, primarily Greek, Roman and Persian.

1968 A turning point in Ghent.

How Chinese porcelain was introduced into the Collection

We had gone there for the weekend. All the shops were closed except for the one that sold Chinese porcelain. Myrna was reluctant to go in, because she said she hated that “heavy black Chinese furniture with ball and claw feet.” But it started to rain and so Chance ushered us in. The owner, Mr. Morant, was ebullient and welcoming. He had a fistful of mimeographed sheets explaining Chinese porcelain and was eager to give us a tour of the offerings. Actually it became more and more interesting as he went on — so much so that we almost missed dinner.

About an hour later we asked, “If we were to collect Chinese porcelain, what would you recommend?” His answer, without hesitation, was “17th century Chinese blue and white” and so we started to make choices and ended up with a series of cups and saucers, a couple of bowls, a small vase and a large plate decorated with the great wall of China. Excited by the venture, we added to the trove the next morning.

About an hour later we asked, “If we were to collect Chinese porcelain, what would you recommend?” His answer, without hesitation, was “17th century Chinese blue and white” and so we started to make choices and ended up with a series of cups and saucers, a couple of bowls, a small vase and a large plate decorated with the great wall of China. Excited by the venture, we added to the trove the next morning.

Kangxi period

Series of small vases, 15.2 cm (Vung Tao cargo)

Statement by Jean-Paul Desroches

Senior Curator of the French National Patrimony

“The Myers Collection of items from a mid-17th century cargo includes examples of the best Transitional porcelain found on the ocean floor.”

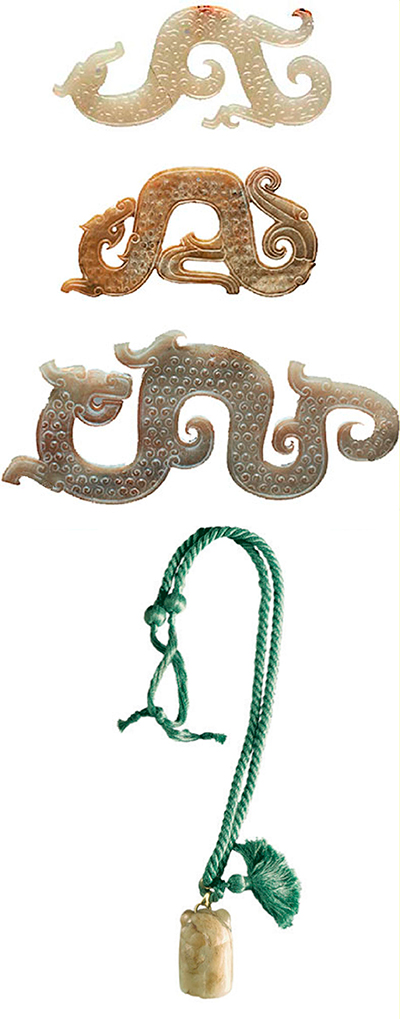

1974 How they got interested in Jade

We had been collecting Chinese porcelain for several years. I would visit antique shops whenever I travelled — which I did three or four times a month. After each trip, I would show Myrna what I had found.

We had been collecting Chinese porcelain for several years. I would visit antique shops whenever I travelled — which I did three or four times a month. After each trip, I would show Myrna what I had found.

At one point in 1974, Myrna said, “I am getting pretty tired of Chinese porcelain. Why don’t you see what else you can find?”

Puzzled, I asked, “Well, what would you like?”

She said, “I don’t know. Maybe sculpture or jade.”

I had discovered a shop on a side street in central Philadelphia. It was a very strange, old fashioned place, It was run by Mr. Fiorillo who had been there for at least 50 years.

I asked Mr. Fiorillo if he had any jade. Gruffly he said he had some jade carvings, but he didn’t put them out because “people steal them.” He offered to show them to me, but said that if I was interested I had to buy the lot.

After some trouble, he located a shoe box which held 60 small jade carvings and hastened to tell me he knew nothing about them and did not guarantee them. I was fascinated, but I too knew nothing about them, never having considered jade before. The price was $1000 for the lot, which at that point was a lot of money for me. After much discussion, he agreed to let me buy them subject to Myrna’s liking them. If she didn’t, I could return them.

(When we got them) We carefully examined each piece, but regardless of our efforts couldn’t unlock the secrets. The adventure to understand jade had begun.

We took the collection to Dr. Rosenbaum, but he could not shed any light on the pieces. Neither could Mr. Kohler, another antique dealer in Ascona; nor could the local jeweler. Our interest only increased with each dead end. Finally we decided that we would keep the group nevertheless.

That was the start of more than 40 years of study and research. The shoe box, which was the beginning of our collection, held Chinese and pre-Columbian jades ranging from the Han Dynasty to the 19th century. It included the Han cicada which Myrna wore for years.

Statement by Jean-Paul Desroches

Senior Curator of the French National Patrimony

“The Myers Collection of archaic jades is one of the richest and most complete private collections in the West, ranging from the Neolithic period (3000 bc) through the first dynasty, Han (206 bc – 220 ad), and ending with the Yuan (1279 – 1368).”

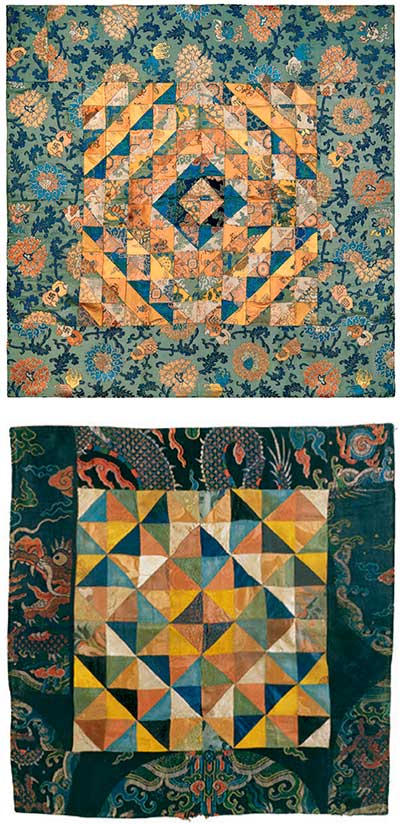

1974 Why Textiles? Myrna Myers’ explanation

Strolling through the Maastricht Fair in 1974, we were struck at first sight by the unusual silks shown by Moke Mokotoff, when textiles from Tibet were beginning to appear in the West. They aroused our curiosity and their rich colors and designs seemed the perfect complement to the subdued palette of classic Chinese porcelain I had been exhibiting.

Strolling through the Maastricht Fair in 1974, we were struck at first sight by the unusual silks shown by Moke Mokotoff, when textiles from Tibet were beginning to appear in the West. They aroused our curiosity and their rich colors and designs seemed the perfect complement to the subdued palette of classic Chinese porcelain I had been exhibiting.

After our initial acquisition, we found searching for the then little shown Far Eastern silks added to their appeal. Chinese textiles soon became a special if eccentric feature of my gallery. Inevitably, Krishna Riboud, the Paris-based textile scholar and collector, came to see my display. She was just then contemplating the foundation of an Asian textile study center, the AEDTA. She and the AEDTA were thereafter an incalculable encouragement to concentrate on textiles. I was a regular visitor to the Center, became familiar with the collections and attended conferences there.

Eventually Krishna Riboud suggested my contributing an essay on her Chinese furnishing silks for publication in “In Quest of Themes and Silks” and later entrusted me with the introduction and legends for her album “Chinese Buddhist Silks”.

At the Center or in informal gatherings in her exotic, connoisseur’s apartment, Krishna Riboud was a regal presence evoking her future projects in an incense-fragrant atmosphere in which everything seemed possible. It is to her that I owe my initiation into the circle of textile enthusiasts and the beginning of a real apprenticeship in Asian textiles.

Early on, I was fascinated by the idea, discovered in John Vollmer’s texts, that the dragon robe might be read as a cosmic vision, since Ming and Qing costumes and costume fragments were at the core of our developing collection.

1976 Myrna becomes an antique dealer in Paris

after graduating from the Ecole du Louvre

By SAM MYERS

In 1976, when Myrna decided to open the gallery, she asked for advice, the response was brutal: “Don’t even think of about it. You would have to be crazy. They are all ‘des requins’ in Paris. They will eat you alive. Especially since you are not only American, but a woman!

Nevertheless the gallery opened in the Fall.

The expertise of Myrna Myers through her texts

Porcelain from a Chinese Junk

By MYRNA MYERS

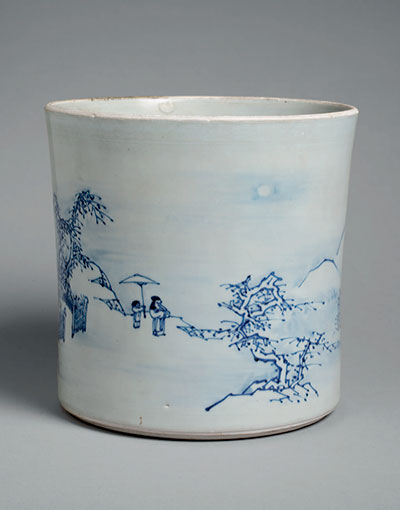

It is exceptional to find a homogenous group of Chinese Porcelain whose dating and provenance are certain, such as the 17th century blue and white recovered from a shipwreck in the South China Sea.

It is exceptional to find a homogenous group of Chinese Porcelain whose dating and provenance are certain, such as the 17th century blue and white recovered from a shipwreck in the South China Sea.

These pieces were discovered and recovered by Captain Michael Hatcher from a junk perhaps destined for a Dutch merchant ship anchored in Batavia (Jakarta) or Formosa. The cargo was comprised of two types of ceramics. The major part was blue and white porcelain decorated in compartments for Dutch taste, called “Kraak,” which was used for tableware. It is similar to other pieces found during a recent salvage of the Witte Lieuw which sank in 1613.

The other porcelain was purely in Chinese taste, which evolved in the beginning of the 17th century and continued until 1660. Known as Transitional ware, it was made during the short period between the Ming and Qing dynasties. The Transitional period was one of the most troubled in China’s history. The disintegration of the Ming dynasty resulted in the abandonment of official control of the production of porcelain. Potters were free from the previous constraints of court taste to innovate and satisfy the desires of clients from popular, bourgeois and intellectual classes.

At the same time, commerce continued with Japan, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Potters created new and original forms. Artists were free to express their inspiration. The success of these novelties was confirmed by the enormous quantity of porcelain which was regularly shipped from Chinese ports during the period. The governor of Batavia complained that he had to stock 800,000 pieces which were on their way to Amsterdam.

The variety of forms is one of the originalities of Transitional porcelain. The pieces were characteristically made of solid white porcelain carefully modeled. The purity of the silhouette and the search for harmony in the proportions are characteristic of this period. Rouleau vases replaced the meiping which had been popular previously.

The variety of forms is one of the originalities of Transitional porcelain. The pieces were characteristically made of solid white porcelain carefully modeled. The purity of the silhouette and the search for harmony in the proportions are characteristic of this period. Rouleau vases replaced the meiping which had been popular previously.

Brushpots were made in porcelain for the first time. Wine pots were created in globular, ovoid or peach-like forms. Among the most unusual pieces are the disked kendi, found for the first time in this cargo. This range of forms was accompanied by an enlargement of the subjects and a greater liberty in the manner in which the décor was executed.

Themes were borrowed from popular literature, from landscape painting, or from album leaves of birds and flowers. A resolute figurative language developed, breaking with the symbolism of the preceding dynasty.

Continuous compositions were balanced and played against the white background. The full moon was often represented in the landscape with rolling clouds. Blades of grass in the form of “V’s” appeared as distinctive signs of the Transitional period.

The painter’s brush is rapid and vital, using fine lines or graduated washes. The soft tones of blue against a slightly tinted white were known in the West as “violets in milk” and in China as “the face of a ghostly blue.” This added to the poetry of the pieces.

The painter’s brush is rapid and vital, using fine lines or graduated washes. The soft tones of blue against a slightly tinted white were known in the West as “violets in milk” and in China as “the face of a ghostly blue.” This added to the poetry of the pieces.

Transitional ware reflected a purely Chinese sensitivity, despite the fact that they were destined for foreign lands, and the distinction between porcelain made for China and pieces destined for export became increasingly less clear.

The Art of Goa

By MYRNA MYERS

In the last years of the 15th century, a page turned in the history of the world: the discovery of “The Indies” in 1492 opened a new era for Europeans. The great navigators — Christopher Columbus toward the West and Vasco de Gama toward the East — delivered the secrets of the maritime routes.

In the last years of the 15th century, a page turned in the history of the world: the discovery of “The Indies” in 1492 opened a new era for Europeans. The great navigators — Christopher Columbus toward the West and Vasco de Gama toward the East — delivered the secrets of the maritime routes.

Many motivations inspired the voyagers: to expand the territories of Spain and Portugal, the search for spices and luxury products, and the fervor to propagate Christianity.

The Portuguese reached the west coast of

India and settled in Goa in 1511.

Throughout the 16th century, evangelists accompanied the intrepid sailors: Franciscans,  Dominicans, Augustinians, and in 1542 the Jesuits with Saint Francis-Xavier.

Dominicans, Augustinians, and in 1542 the Jesuits with Saint Francis-Xavier.

They knew how to adapt their messages of faith to local customs, singing prayers in the streets. Monasteries and churches multiplied and needed cult images for the new altars.

The religious orders turned to Indian artists.

At that time the Indian continent followed Buddhist and Hindu traditions. Having mastered the art of making religious sculpture in wood, stone, metal and ivory over the centuries, the Indian workshops were able to respond to orders which flooded the market. Thus a new art form, named in the 19th century “Indo-Portuguese,” developed, based on a mixture of exotic and appealing Buddhism, Hinduism and Christianity.

The first images in ivory were created to illustrate the life and Passion of Christ in which the figures were shown in hierarchic positions, with simplified volumes and little detail.

In the 16th century, there were similarities to gothic sculpture. The figures were often inspired by engravings and small sculptures which were brought to India by the Europeans.

By the 17th century, the differences between Goa ivories and their original models were more marked, the gestures and faces were more expressive.

The naïveté of the 17th century was superseded in the 18th century, when the movement of the draperies was more developed.

The ivories of Goa are distinguished from many Christian images by their treatment of the figure of Christ and by the importance given to the cult of the Virgin.

These images, sometimes naïve, sometimes majestic, relate one of the most passionate and moving chapters in the history of our world — the beginning of the modern era.

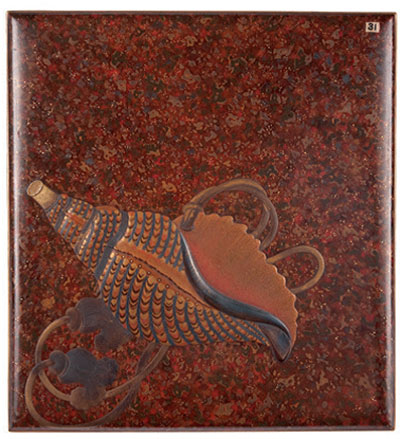

The Fruit of Patience: Japanese Lacquer

By MYRNA MYERS

The art of using lacquer to protect and decorate objects was developed in Japan in a unique manner, despite the fact that the material was particularly difficult to work with.

The art of using lacquer to protect and decorate objects was developed in Japan in a unique manner, despite the fact that the material was particularly difficult to work with.

It required knowledge of the various steps of fabrication, which could only be acquired by years of apprenticeship. Knowledge was traditionally transmitted by a master lacquerer to his followers.

Lacquer or urushi comes from the sap of a tree, rhus verniciflua, which is slowly gathered and has to be filtered and purified before use. It has the consistency of thick honey and is applied in fine coats, usually spread on a wood core which has been impeccably finished and covered with fabric.

Suzuribako

lacquer, Japan, Edo period, 4 × 22.5 × 24.5 cm

(Cartier-Bresson Collection

Box

Box

lacquer, Japan, Edo period, 8 × 10.5 × 9 cm

(Cartier-Bresson Collection)

To construct a lacquer object with a smooth and durable surface requires about thirty successive operations, since each layer has to dry and be polished before the next layer can be applied. If one adds the time needed to conceive and realize the decoration, it is clear that a work in lacquer may take months or even years of intermittent work to complete.

Many techniques of decoration are used in Japan, some coming from the contacts with China and Korea. Nevertheless, the singularity of Japanese lacquer art and its fame are founded on the exploitation of the technique called maki-e, the sprinkling of particles of powered gold or silver on the carved surfaces of moist lacquer.

The décor of these pieces is often inspired by observation from nature, the changing of the seasons, the view of familiar landscapes and famous sites.

Certain subjects or scenes refer to Japanese literature, with images intended to convey symbolic meaning. This evocative scene results from a mastery of all the techniques of lacquer art combined in one noble object. In the past, these luxurious accessories were reserved for aristocrats of the court and military leaders. Today we can all enjoy the rewards of patience.

Poems to Wear

By MYRNA MYERS

The long robe worn by men and women since the 16th century, the kimono, is symbolic of Japan. It derives from the kosode, which is much older and served as the undergarment of aristocrats as well as others. Its form in a “T” is fashioned from four bands of material folded in two and stitched side by side to form the sleeves and body of a robe which opens in front.

The long robe worn by men and women since the 16th century, the kimono, is symbolic of Japan. It derives from the kosode, which is much older and served as the undergarment of aristocrats as well as others. Its form in a “T” is fashioned from four bands of material folded in two and stitched side by side to form the sleeves and body of a robe which opens in front.

Figure of a No – actor

polychrome wood Japan, Momoyama period, 52 cm

When worn, one panel crosses the other and is retained at the waist by a fabric belt, the obi. Reduced to its essentials, it is astoundingly modern. The kimono offers an ideal background for decorative propositions which are often unique, drawn from an inexhaustible iconography. The result is so many poems to wear.

The Edo period (1603 to 1868) was propitious for the creation of kimonos for citizens of the towns which were in full development. Thanks to the peace imposed by the Tokugawa shoguns, commerce prospered, the pleasure quarters were organized and everyone was interested in style.

The weavers established their workshops in Kyoto and manufactured kilometers of silks and brocades — weavings with polychrome designs and gold threads were the specialty. Many of their sumptuous creations were destined for the No – theater, a mixture of rite and dance which presented scenes of mysterious tales played by masked actors to melancholic music.

No– robe

silk brocade,Japan

Edo period, 165 × 148 cm

The costumes replaced the stage décor and needed to evoke the condition and moral qualities of the characters by their colors and their motifs.

The extreme richness of No– robes is the result of their being woven so that they appear to be in relief, with designs which overlay one another.

The stiff silk used for these robes creates exaggerated and sculptural silhouettes which accentuate the strange atmosphere of these spectacles.

Noshime

Japan, Edo period,

155 × 140 cm

Simpler robes are also found in the No – theater such as the noshime.

Worn under a vest, and with very ample pantaloons, this costume would be used at the comic interval, Kyo – gen, which accompanies the more serious representation of No–.

This robe with its supple horizontal bands and grilllike patterns is dyed with indigo using an ikat technique.

The choken in green gauze

Is decorated with peony branches and phoenix, the emblem of the empress of China, which was adopted by Japan.This sort of light vest would be worn over a kimono to add to the decorative aspect as a sort of tinted mist highlighted with glittering gold. Choken. silk gauze with gold embellishment, Japan, Edo period, 74 × 152 cm

During almost a thousand years the shoguns made and unmade the imperial history of Japan, supporting sovereigns before replacing them. Their clothing developed naturally in relation to their armor which was articulated, made of leather and plaques of iron, bronze, lacquer and silk cords, resulting in ferocious beauty.

Hitatare

Japan, Edo period,

141 × 152 cm

The hitatare is composed of a vest and pantaloons, the hakama.

It was originally worn under the armor, but later adopted by samurai for civil use.

The décor of this example consists of rows of chrysanthemum which alternate with white medallions against a background of clouds.

The palette of green, white and violet against beige is also used in the silk cording which adds an additional note of color.

Jimbaori

Worn over the armor became a symbol of prowess and rank. Plumes, imported wool or tapestry were among the exotic materials used. The mon on jimbaori are emblems which historically, just as a coat of arms in the West, indicated the warrior’s membership in a family or powerful clan. It is a reduction of an image to a simple or graphic design. In the Edo period, these designs were placed at designated places on garments as symbols of rank.

LEFT: Jimbaori, Japan, Edo period, 81 × 70 cm RIGHT: Jimbaori, Japan, Edo period, 96 × 71 cm

Kamishimo

Japan, Edo period, 138 x 77 cm

The mon is the only motif immediately recognizable on the kamishimo.

Originally worn by the shogun, it was reserved for use by the samurai.

This two-piece vestment created a distinctive silhouette due to the rigidity of the tissue, a pleated ramie used to construct the upper portion (kateginu) and the pantaloons (hakama).

The actual décor of this kamishimo consists of thousands of white spots in reserve which suggest a hail storm, a metaphor for the power of the warrior.

The Manjuwa

Japan, Edo period, 49 × 47 cm

The Manjuwa is a short costumes without sleeves, offered supplemental protection under the armor which hid its gold brocade. Nevertheless, the choice of decorative motifs was appropriate for the battlefield: confronting dragons are images of power inherited from China; the design of hitokiku, tortoiseshell, , embroidered on the collar is a wish for long life; the miniscule iris on the trimming, called shoba, are symbols of fidelity in accordance with the samurai code. Many of the themes found in Japanese costumes form an ode to life or to nature in harmony with man.

The Love of Color–Ikats and Embroideries of Central Asia

By MYRNA MYERS

Khalat

Khalat

Embroidered silk brocade, Uzbekistan,

19th c., 139 × 210 cm

The peoples of Central Asia knew how to brighten the desert with an explosion of silk colors.

With accomplished techniques of dying and embroidery, they embellished robes, accessories and wall hangings. Even horse trappings were fashioned in vibrant silks.

These pieces illustrate the renaissance of textile arts in the 19th century in towns along the ancient Silk Road.

Khalat Detail

Ikat, a word derived from the verb meaning to tie, refers to a technique of dying before weaving. It consists of tying the strands of silk destined to be used in weaving at various specific points to create motifs which, after a succession of baths in different colors, reveal the intended designs. The threads are then woven with a cotton warp.

Bukhara, Samarkand and Marghila in the valley of Ferghana were the centers of such weaving in Uzbekistan, each with its own particular styles and colors. The area was rich in the basic materials: silk, cotton and dyes.

The habile artisans belonged to various ethnic groups: Tadjiks, Uzbeks, Arabs, Persians and Jews.

They organized by specialties. Clients came from all levels of society: the people adored being enveloped in flaming colored silks. The favorite colors were red and bright rose, purple, yellow, blue indigo, turquoise and lemon green.

The motifs suggested amulets, jewels, flowers, fruit, palmettes and trees, but everything was transformed into continuous decoration with repetition and abstraction. In this land of merchants and cavaliers, the clothing — tunic, pantaloons and a coat — stayed the same for a thousand years and can be seen today in the apparel of the 19th century. The long robe, chapan or khalat, is the key element of the wardrobe. It is worn belted by men over a shirt with a horseman’s trousers and boots.

Chapan

Embroidered felt, Uzbekistan,

19th – 20th c., 118 × 192 cm

One would also wear a grand turban or a calotte, a smaller head covering. The colors chosen varied according to the locality from the liveliest to the relatively sober.

The robe could be very long and ample with large sleeves or, on the contrary, cut close to the body with short straight sleeves. Women also wore the chapan, but without a belt, over a light robe or trousers. That would be completed with a hair covering or shawl without a veil.

The costumes were lined with printed cotton decorated with flowers or stripes, often of Indian or Russian origin. The more worked khalat were generally lined with Central Asian ikats. They were often finished with bands of contrasting embroidery which served as borders and resulted in surprising juxtapositions. Thus the vision of a multicolored garden emerging from the sands is not always a mirage.

The Art of the Tea Ceremony

By MYRNA MYERS

The preparation and drinking of tea in a ritual manner became a living tradition in Japan which called for selecting utensils appropriate for each unique gathering of devotees. Among the essentials are the tea bowl (chawan); the jar for powdered tea (cha-ire); the storage jar for leaves (chatsubo); the fresh water jar (mizusashi); the kettle (kama); the incense burner (koro); an incense box (kogo); and a vase for flowers (hana-ire).

The preparation and drinking of tea in a ritual manner became a living tradition in Japan which called for selecting utensils appropriate for each unique gathering of devotees. Among the essentials are the tea bowl (chawan); the jar for powdered tea (cha-ire); the storage jar for leaves (chatsubo); the fresh water jar (mizusashi); the kettle (kama); the incense burner (koro); an incense box (kogo); and a vase for flowers (hana-ire).

If special foods are offered, serving dishes (mukozuke) are needed. The ceramics, lacquer, metalwork and bamboo tea utensils which accorded with the aesthetic criteria set by successive tea masters have been revered for centuries.

Powdered green tea was brought from China by Buddhist pilgrims. Whipped to a froth with hot water in a bowl, the tea was drunk as a stimulant to concentration during meditation or passed among the monks during commemorative rites, associating tea and Zen from the beginning of its adoption in Japan.

Chawan, pottery

Karatsu ware, Japan, Momoyama period, 19 × 15.3 cm

By the 14th century, however, tea drinking was favored by the aristocracy and became the pretext for extravagant parties during which prestigious collections of Chinese treasures were displayed.

The ritual of the tea ceremony evolved in the 15th century from teachings of the early tea masters, cultivated Buddhist monks serving as aesthetic advisors to powerful warlords.

Every aspect of the environment was arranged to contribute to an atmosphere of harmony and serenity. The predominant aesthetic principle was a quest for purity with which the noble monochrome ceramics of Song and Yuan China accorded

perfectly.

During the 16th century, the moral and philosophical implications of the Way of Tea became more profound. They were consolidated by the most influential of the tea masters, Sen no Rikyu (1521 – 1591). Such notions as wabi (quiet solitude) and sabi (time-worn, natural) were to guide devotees away from a search for material perfection toward an ideal of spiritual honesty. The atmosphere of the tea room drew closer to monastic simplicity.

While Chinese ceramics were not rejected, tea masters sought humbler wares, preferring rustic pieces which might have served common people. The pottery of Japan’s ancient kilns was rediscovered and highly valued. Ceramics of contemporary Korean potters were similarly appreciated. Thus wabi-cha prepared the awakening of a uniquely Japanese ceramic sense and the unfurling of its creativity.

Ewer, porcelain

kinrande ware, China, Ming dynasty, 20 cm

In the early 17th century, Japan enjoyed an exceptional period of domestic tranquility and prosperity. Tea drinking became a tradition throughout society and the demand for tea utensils increased sharply. The time was ripe for fresh new ceramic styles. Ancient kilns formerly devoted to unglazed utilitarian wares began to produce specific tea utensils.

Korean-inspired kiln wares were chosen for their simplicity and naturalness. But tea ceremony followers reserved their greatest admiration for innovations of color and pattern and eccentric forms.

Tea masters such as Furuta Oribe (1544-1615) encouraged a new audaciousness in ceramics by patronizing kilns and designing their own pieces. Raku tea bowls, entirely molded by hand, were another example of unique creations by artist potters.

Keeping pace with early Edo desire for more decorative utensils, both blue and white and polychrome porcelains were imported from China. Distinctive by their curious shapes and poetic décor, these pieces often reflected specific requests from the tea masters. Meanwhile, elegant Kyoto society was developing a taste for refinement and richness, reflected in the theory of “beautiful wabi” defined by Kobori Enshu (1579-1647), implying a return to a connoisseur’s attitude toward tea ceremony utensils as objects of art. This reinterpretation of wabi reflects the diversity of schools and styles which characterize the evolution of tea taste in modern times.

The texts of this article have been extracted from

the catalogue of the exhibition “From the Land of Asia”

where the Sam and Myrna Myers Collection

is presented at the Kimbell Art Museum.

Authors:

Sam and Myrna Myers

Also with texts by:

Jean- Paul Desroches. Senior Curator of the French National Patrimony

Héléne Bayou. Chief Curator, Japanese Art, National Museum of Asiatic Art–Guimet. Gilles Béguin. Senior Curator of the French National Patrimony.

Pierre Cambon. Chief Curator, Korean Art, National Museum of Asiatic Art–Guimet. Isabelle Leroy-Jay Lemaistre. Former Curator, Sculpure Department, The Louvre. Filippo Salviati. Professor, Department of Oriental Studies, “La Sapienza” University, Rome and John E. Vollmer. Research Associate, Royal Ontario Museum.

Photographs: Thierry Ollivier

Hardcover

Pages: 280

Publisher: Lienart (4 Nov. 2016)

Language: English, French

ISBN-10: 2359061852

ISBN-13: 978-2359061857