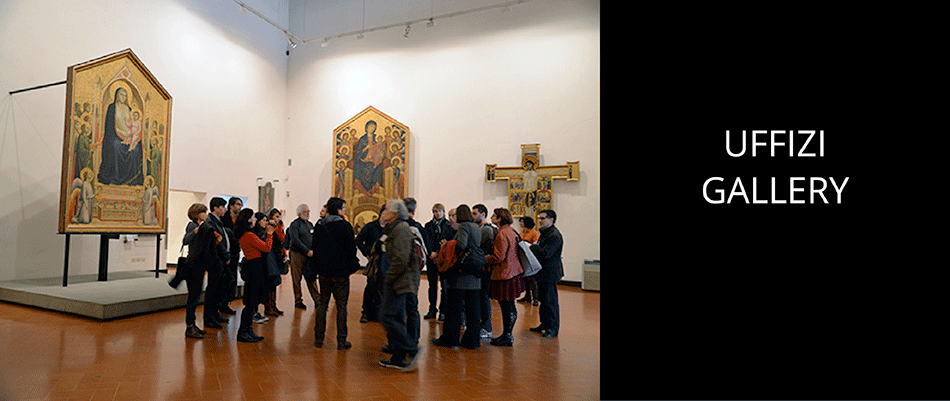

Panel paintings workshop participants visiting the Uffizi Gallery in late 2013. Photo: Aleksandra Hola

As a conservator passionate about the structural treatment of old master paintings, I probably see something different than the average viewer when I look at paintings, in particular if they are panels.

In addition to admiring the artwork, I have been trained to understand its materials. Knowing how to conserve paintings is as much about the history of the artwork as it is about consulting the current cohort of peers who may often be thousands of miles away. My recent participation in residencies and trainings supported by the Getty Foundation through its Panel Paintings Initiative provided the opportunity to do both: to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to conserve these complex paintings and to unlock a network of experienced professionals with whom to discuss them.

Along the way, I’ve developed a great appreciation for the skills needed to do this work. Being a good conservator is a bit like being a detective: looking closely, examining the facts, searching for clues that might be hidden at first glance, and calling in expert backup when you don’t have the answer.

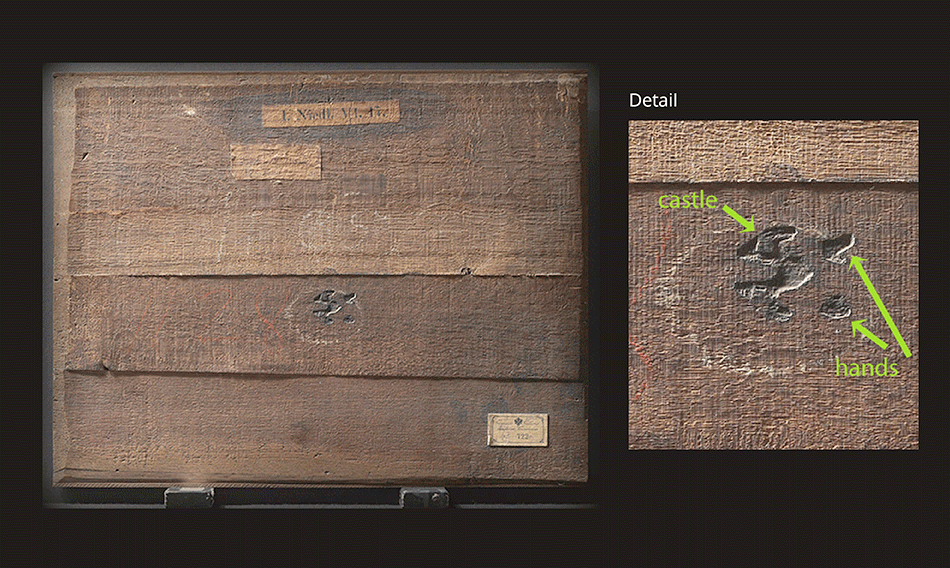

Sara Mateu examines the reverse of a panel painting

Sara Mateu examines the reverse of a panel painting

Looking at a Painting as a Conservator

Any conservator tasked with the care of an artwork needs to fully understand it before designing a treatment protocol. For a conservator, the surface is only the beginning. The same analysis that scholars might apply to the front of a painting—assigning it to a style, a school, a period, and an artist—can be done with the support by looking carefully at its reverse. If the original panel is still relatively intact, tool marks, makers’ stamps, labels, and even signatures can provide important information on the artwork.

A painting is full of information about its provenance, the process of its making, and the people involved in its manufacture…if you know how to read it

Panels manufactured in Northern and Southern Europe are different in in terms of materials and techniques. Once one knows about the type of wood, the construction, the condition of support and the paint film, and the environment in which the painting been housed, it is possible to understand why and how alterations have occurred.

Take a close look at the wood in the example above. We can tell from the grain design that it is oak, radially cut. We know that Flemish painters favored oak over other woods. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Baltic oak was imported from Poland because it was a high-quality material: it had a very straight grain without defects and its slow growth assured workability and good behavior of the panel. In the 17th century it became scarce, and panel makers switched progressively to regionally grown oak, often of a lesser quality.

We can also see some tool marks in the reverse, showing that the wood was cut radially. The very straight, thin, and regular cutting lines suggest a mechanical saw. This is a characteristic often found in 17th-century Dutch and Flemish panels, an effect of the boards being sawed in a wind-powered sawmill. The surface wasn’t finished further. In the 15th and 16th centuries the boards were obtained and finished by other methods, such as manual saws, cleavers axes, adzes, and a variety of planes, with each tool leaving a distinctive mark.

However, the main evidence of origin in this case is the Antwerp brand on the center of the reverse. Panels manufactured in Antwerp in the 17th century were sometimes subjected to the approval of the Guild of Saint Luke. The guild had branding irons representing the coat of arms of Antwerp: a castle and two hands. Upon approval of the dean and probably the payment of some sort of tax, the panel was branded as a mark of distinction of its quality and provenance.

All of these signs together point to a 17th-century Dutch painting. The work is Dulle Griet by David Ryckaerts painted in the 1650s and now in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. (I was able to contribute to the conservation and study of this work as part of my Panel Paintings Initiative training).

During conservation work, a strainer was attached to the reverse of Vasari’s Last Supper using a spring mechanism

Just as the marks on a panel tell us about its origins, evidence of past repairs can sometimes tell us where and when the work took place. When restoring paintings, most conservators aim to secure the artwork with the minimum possible intervention, but conservation practice has evolved in different ways in different regions of the world.

The photo above shows a strainer (auxiliary support) attached to a panel by way of a spring mechanism. This is characteristic of the Florentine school of panel paintings conservation, which suggests that the repair was done by a conservator with a background in Italian conservation techniques. And indeed, this is the auxiliary support used in the structural treatment of Vasari’s Last Supper, one of the major training grants of the Panel Paintings Initiative undertaken at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence.

In Northern Europe, London-based conservators have developed an unattached auxiliary support that is easy and inexpensive to manufacture. To increase the strength without stressing the panel in critical cases, they have introduced laminated battens. In all cases, conservators share these solutions with one another to test their ideas and incorporate each other’s suggestions.

The Importance of Sharing

Christina Young discussing the treatment of the Gerino da Pistoia panel at the Courtauld as part of the Panel Paintings Initiative during this spring’s SRAL workshop in London. Photo courtesy SRAL

Depending on how they were constructed, panels can display great variation in their conservation issues. In the past, conservators from Northern and Southern Europe faced different problems, and in a pre-globalized world they developed different approaches and techniques. Today conservators share these regional solutions with each other. The Panel Paintings Initiative has made it a priority for conservators like myself to learn as much as possible about the range of approaches.

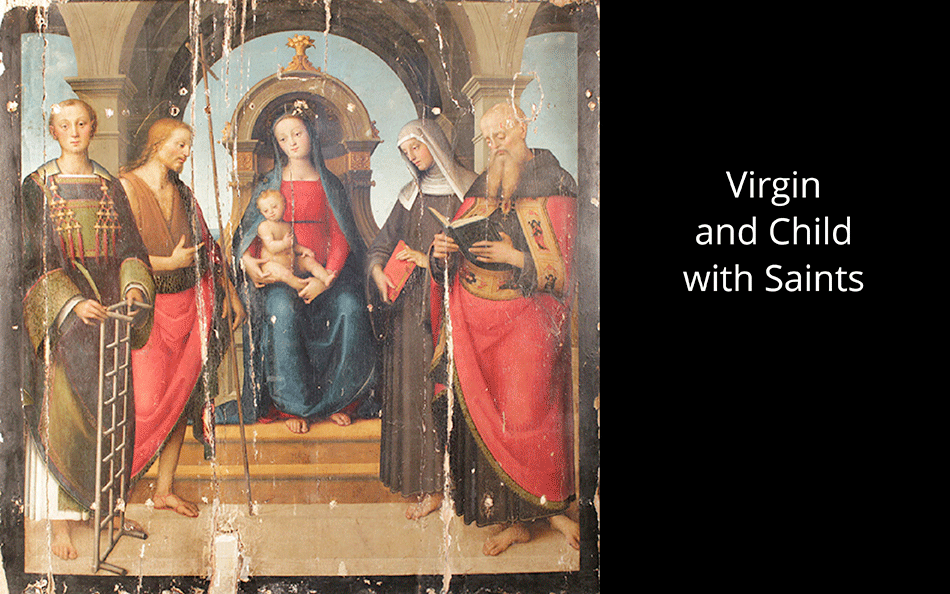

When participants in a Panel Paintings Initiative workshop recently visited the Courtauld Institute of Art, one of the host institutions for training, we learned about the complicated treatment of an Italian Renaissance painting by artist Gerino da Pistoia. The treatment had been postponed due to the delicacy of the work’s structural condition. Prudently, the conservators in the UK who were in charge of the collection acknowledged how challenging the work was and enlisted the expertise of Italian conservators. Now that the structural work has been completed and the picture is stable, treatment can be undertaken on the painted surface.

Gerino da Pistoia, Virgin and Child with Saints, 1510, Panel after removal of cradle, completion of split repair, and attachment of new auxiliary support. The Courtauld Gallery, London. Photo: Christina Young

Gerino da Pistoia, Virgin and Child with Saints, 1510, Panel after removal of cradle, completion of split repair, and attachment of new auxiliary support. The Courtauld Gallery, London. Photo: Christina Young

Always Learning

Panel paintings conservation is a fascinating field in constant evolution, and there is always something more to learn.

Through the Getty’s Foundation’s Panel Paintings Initiative, I and many others have received training from international experts and completed residencies in conservation studios across several countries. For example, we participated in a series of conservation workshops organized by SRAL (Stichting Restauratie Atelier Limburg, a leading conservation studio in the Netherlands) and supported by the Getty Foundation as part of its Panel Paintings Initiative. The workshop brought together experts from around the world, and a group of postgraduates who will become the next generation to care for these paintings, to review projects carried out with the Getty Foundation’s support over the last several years.

These opportunities have contributed enormously to my professional development. I have had extraordinary mentors with whom I continue to share my experiences, questions, and achievements. The experience of working with conservators from different countries and backgrounds widened my views and taught me the value of tradition and the importance of innovation. I have worked on outstanding paintings with the satisfaction of knowing that I contributed to their conservation and understanding for the generations to come. My experience was very rich because I made good friends along the way, people as passionate as I am for art, conservation, and addressing challenges.