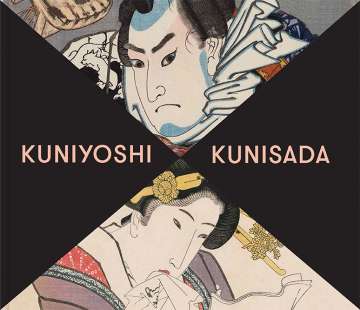

SHOWDOWN! KUNIYOSHI vs. KUNISADA

August 11 to December 10, 2017

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

LEFT: Utagawa Kuniyoshi (detail) RIGHT: Utagawa Kunisada (detail)

Two Japanese Master Printmakers go Head to Head.

Exhibition of 100 Colorful Prints

Rival artists Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) and Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1864) were the two best-selling designers of ukiyo-e woodblock prints in 19th-century Japan. Featuring 100 works drawn from the preeminent Japanese collection housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), Showdown! Kuniyoshi vs. Kunisada revives the centuries-old competition and invites visitors to decide which of the two artists is their personal favorite.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1845, “Nozarashi Gosuke, from the series Men of Ready Money with True Labels Attached, Kuniyoshi Fashion”. (Kōka 2) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1845, “Nozarashi Gosuke, from the series Men of Ready Money with True Labels Attached, Kuniyoshi Fashion”. (Kōka 2) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III) 1820s “The In-demand Type, from the series Thirty-two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Nellie Parney Carter Collection—Bequest of Nellie Parney Carter. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III) 1820s “The In-demand Type, from the series Thirty-two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Nellie Parney Carter Collection—Bequest of Nellie Parney Carter. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Kunisada was more popular during his lifetime, famous for realistic portraits of kabuki theater actors, sensual images of beautiful women and the luxurious settings he imagined for historical scenes.

Kuniyoshi is beloved by today’s connoisseurs and collectors for his dynamic action scenes of tattooed warriors and supernatural monsters—foreshadowing present-day manga and anime—as well as comic prints and a few especially daring works that feature forbidden political satire in disguise. Many of the prints in the exhibition, are being shown in the U.S. for the first time—including large, multi-sheet images in brilliant color.

Sarah E. Thompson,

Curator, Japanese Art, who organized the exhibition said:

“Kuniyoshi and Kunisada’s wonderful depictions of tattooed warriors, supernatural monsters, kabuki actors and Edo fashionistas are amazingly well suited to 21st-century taste,” . “We are happily rediscovering these great artists and are eager to see how this rivalry will play out in modern times.”

An in-gallery quiz, also available online, poses the question “Are you #TeamKuniyoshi or #TeamKunisada?” and encourages visitors to share their results on social media.

Kuniyoshi and Kunisada were the star pupils

Pupils of Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825), who was the second head of the famed Utagawa school of ukiyo-e woodblock print artists. Ukiyo-e, which translates to “pictures of the floating world,” was a genre of paintings and prints that drew their subject matter from fashionable city life, especially the kabuki theater and the Yoshiwara pleasure district. Kuniyoshi and Kunisada took the floating world by storm during the end of the Edo Period (1603–1868), when the mass-produced ukiyo-e prints thrived as an important media for conveying the latest entertainment and fashion reports—a precursor to television and magazines. Members of the general public were thrilled and enthralled by the dashing heroes, beautiful women and other figures portrayed within the works.

The exhibition is organized thematically

Showcasing how Kuniyoshi and Kunisada depicted the same popular subjects—and often riffed off each other’s signature styles. Their prints are distinguished by frame color in the gallery: black ash for Kuniyoshi and cherry for Kunisada. Additionally, the themes recur in the in-gallery and online quiz, which prompts visitors to choose between playful pairings of prints—for example, Kuniyoshi’s triptych of a shipwreck caused by a gigantic sea monster or Kunisada’s triptych of fierce warriors in pursuit of a villain ( #TeamKuniyoshi or #TeamKunisada)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1851–52 (Kaei 4–5) “The Former Emperor [Sutoku] from Sanuki Sends His Retainers to Rescue Tametomo”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1851–52 (Kaei 4–5) “The Former Emperor [Sutoku] from Sanuki Sends His Retainers to Rescue Tametomo”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Details of the triptych “The Former Emperor[Sutoku]

from Sanuki Sends His Retainers to Rescue Tametomo”

The same popular subjects by Kunisada

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1830 (Bunsei 13/Tenpō 1) “Hayakawa Ayunosuke, from the series Eight Hundred Heroes of the Japanese Shuihuzhuan”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of Maxim Karolik. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1830 (Bunsei 13/Tenpō 1) “Hayakawa Ayunosuke, from the series Eight Hundred Heroes of the Japanese Shuihuzhuan”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of Maxim Karolik. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi. 1843–47. “Yan Qing, the Graceful, from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Shuihuzhuan”. (Tenpō 14–Kōka 4); first edition about 1827–30, Bunsei 10 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of Maxim Karolik. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi. 1843–47. “Yan Qing, the Graceful, from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Shuihuzhuan”. (Tenpō 14–Kōka 4); first edition about 1827–30, Bunsei 10 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of Maxim Karolik. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Heroes, Ghosts and Monsters

During the first half of the 19th century, there was a huge boom in adventure stories in Japan—thrilling tales that inspired printed books, kabuki plays and colorful woodblock prints. Kunisada was renowned for his accurate portrayals of famous kabuki actors, inserting them into imaginary scenes from bestselling fantasy novels such as The Eight Dog Heroes of Satomi. A spectacular eight-sheet tower from about 1850—the tallest-known ukiyo-e print, published as four separate diptychs—depicts a rooftop fight scene from the story. Kunisada gave each hero the face of a famous actor, confident that he did not need to identify them because his drawing skills would make them instantly recognizable.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III). 1852 (Kaei 5), 3rd month. “Shirasuka: (Actor Onoe Kikugorō III as) a Cat Monster, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III). 1852 (Kaei 5), 3rd month. “Shirasuka: (Actor Onoe Kikugorō III as) a Cat Monster, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Often, the rival artists depicted the same popular subjects—one example is the story of the nekomata, a fork-tailed cat monster from a kabuki play about a series of supernatural events on the Tōkaidō Road. The role was written for Onoe Kikugorō III, a top star who specialized in ghost plays. An 1847 print by Kuniyoshi commemorates Kikugorō’s grand retirement performance, which had taken place that year, while a later print by Kunisada serves as a fond recollection of the same event, published three years after the actor’s death.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1847 (Kōka 4), 7th month. “An Imaginary Scene of the Origin of the Cat Stone at Okabe, from the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road: Actors Sawamura Sojūrō V (?) as Teranishi Kanshin (R), Onoe Kikugorō III as the Spirit of the Cat Stone (C), and Ichimura Uzaemon XII as Ōe Inabanosuke (L)”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1847 (Kōka 4), 7th month. “An Imaginary Scene of the Origin of the Cat Stone at Okabe, from the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road: Actors Sawamura Sojūrō V (?) as Teranishi Kanshin (R), Onoe Kikugorō III as the Spirit of the Cat Stone (C), and Ichimura Uzaemon XII as Ōe Inabanosuke (L)”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Details of the triptych

Kuniyoshi, meanwhile, gained fame with his imaginary, action-packed portraits of tattooed warriors

His hit series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Shuihuzhuan (about 1827–30) made him a star among ukiyo-e artists, comparable to the older, already established Kunisada. The characters were drawn from a beloved Chinese martial arts novel known in English as The Water Margin (Shuihuzhuan in the original Chinese and Suikoden in Japanese), a story about 108 bandits that was loosely based on the history of 12th century China. In one print, Kuniyoshi portrays Yan Qing, a skilled wrestler, described as having tattoos that cover his entire body. While the subject of the tattoos is not mentioned in the book, Kuniyoshi decorated the hero’s body with lions among peonies, symbolizing courage. Another warrior, Hayakawa Ayunosuke, from the series Eight Hundred Heroes of the Japanese Shuihuzhuan, is depicted with a splendid dragon tattoo, even though large pictorial tattoos were not yet being done in Japan during Ayunosuke’s lifetime. Kuniyoshi himself reportedly had tattoos, and his designs continue to inspire artists today.

Superstars of Kabuki

Kabuki was a core institution of the Edo period. All-male casts delighted their fans with day-long performances that usually combined several different plays, with complicated plots drawn from Japanese history, real-life drama and fantasy fiction. Many actors specialized in different kinds of parts, such as female roles or action heroes, but versatility was also greatly admired. Actor

prints—the equivalent of today’s celebrity photographs—were often sold as a series, and eager fans were not satisfied until they obtained every one. These featured both real and imagined performances, as well as scenes of actors in real life, often modeling the latest fashions for men.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1855 (Ansei 2), 7th month. “Actors Arashi Kichisaburō III as Akabori Mizuemon, with Matsumoto Kunigorō and Arashi Kangorō (R); Arashi Rikan III as Nakano Tōbei (C); and Kataoka Gadō II as Miki Jūzaemon, with Naritaya Sōbei II(?) and Ōtani Tokuji II (L)” . Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1855 (Ansei 2), 7th month. “Actors Arashi Kichisaburō III as Akabori Mizuemon, with Matsumoto Kunigorō and Arashi Kangorō (R); Arashi Rikan III as Nakano Tōbei (C); and Kataoka Gadō II as Miki Jūzaemon, with Naritaya Sōbei II(?) and Ōtani Tokuji II (L)” . Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Details of the triptych

“Plum: Actors triptych”

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III) 1859 (Ansei 6), 8th month. “Plum: Actors Arashi Kichisaburō III as Tōken Gonbei, Comparable to Yang Zhi (R); Ichikawa Kodanji IV as Danshichi Kurobei, Comparable to Ruan Xiaoer (C); and Iwai Kumesaburō III as Yakko no Koman, Comparable to Little Sanniang (L), from the series A Modern Shuihuzhuan”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of William Perkins Babcock. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III) 1859 (Ansei 6), 8th month. “Plum: Actors Arashi Kichisaburō III as Tōken Gonbei, Comparable to Yang Zhi (R); Ichikawa Kodanji IV as Danshichi Kurobei, Comparable to Ruan Xiaoer (C); and Iwai Kumesaburō III as Yakko no Koman, Comparable to Little Sanniang (L), from the series A Modern Shuihuzhuan”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Bequest of William Perkins Babcock. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Details of the triptych

In addition to Kunisada’s sought-after actor prints, this section features a spectacular 1856 six-sheet design by the artist, made up of two triptychs that function either separately or together. They show the dressing rooms at the Ichimura Theater, celebrating the reopening of the building after it was rebuilt following the disastrous earthquake and fire of 1855 that leveled much of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Theater fans could have had hours of fun identifying their favorite stars and discussing the many activities depicted.

Private Pleasures: Surimono Prints

Special prints known as surimono, unlike other ukiyo-e prints, were not commercial products made for sale in stores. Instead, they were commissioned by private patrons, who were willing to pay for the most lavish materials and printing techniques. Visitors are encouraged to look at the prints in this section from different angles to spot fine details such as metallic pigments or embossed designs.

Surimono prints featured a wide range of subject matter, including landscape and still life, but since Kuniyoshi and Kunisada were famous for their outstanding skill in drawing human figures, they were most often commissioned to create images of kabuki actors or beautiful women. Highlights of this section include two especially fine surimono triptychs—one by Kunisada and one by Kuniyoshi—commissioned by the same patron, Lord Mōri of the Chōshū domain, to show ideal performances that had not yet occurred in real life. Kunisada’s print (about 1829) portrays a scene from one of the most famous of all kabuki plays, Sukeroku and the Cherry Blossoms of Edo, featuring the swashbuckling hero Sukeroku and his lover Agemaki, the most beautiful courtesan in the Yoshiwara. Kunisada cast two top stars, Ichikawa Danjūrō VII and Iwai Kumesaburō II, in the roles, joined by Onoe Kikugorō III as Sukeroku’s brother Shinbei. Fans loved seeing Danjūrō and Kikugorō perform together because of the sizzling rivalry between the two handsome superstars, but this particular performance never actually materialized. Kuniyoshi’s print (about 1835–36) portrays the same actors—Onoe Kikugorō III and the former Ichikawa Danjuro VII, now using the name Ichikawa Ebizō V. In the fall of 1836, a play with this ideal cast was indeed produced in Edo, but sadly, Lord Mōri, the patron, died of illness at just that time.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), about 1829 (Bunsei 12). “Actors Iwai Hanshirō V as Agemaki (R), Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Sukeroku (C), and Onoe Kikugorō III as Shinbei (L)”. Woodblock print (surimono); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), about 1829 (Bunsei 12). “Actors Iwai Hanshirō V as Agemaki (R), Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Sukeroku (C), and Onoe Kikugorō III as Shinbei (L)”. Woodblock print (surimono); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Details of the triptych

Actors triptych

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1835-36 (Tempō 6-7) “Actors Onoe Kikugorō III as Nagoya Sanza (R), Iwai Hanshirō VI (C), and Ichikawa Ebizō V as Fuwa Banzaemon (L)”. Woodblock print (surimono); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1835-36 (Tempō 6-7) “Actors Onoe Kikugorō III as Nagoya Sanza (R), Iwai Hanshirō VI (C), and Ichikawa Ebizō V as Fuwa Banzaemon (L)”. Woodblock print (surimono); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Details of the triptych

Edo Fashionistas

From the beginning of ukiyo-e printmaking in the late 17th century, images of beauties, known as bijin-ga, were a major category of subject matter. Depictions of lovely young women in the latest outfits could serve as both pinups for men and fashion plates for women, providing a wide range of potential customers for printmakers. The most famous beauties of all were the top-ranked

courtesans of the Yoshiwara, who were fashion icons much like the supermodels and female pop stars of today. Most of the women in prints by Kuniyoshi and Kunisada, however, are not courtesans. Some are geisha—entertainers who provided music, dance and witty conversations at parties. Geisha were required by law to dress more plainly than courtesans, but turned this restriction into their own refined form of elegance. Many of the beauties are ordinary townswomen of the middle or even upper class, displaying their fashion sense through their choice of kimono fabrics, hairstyles and makeup—and inspiring viewers of the prints to try similar styles.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1844 (Tenpō 15/Kōka 1) “Takeout Sushi Suggesting Ataka, from the series Women in Benkei-checked Fabrics”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1844 (Tenpō 15/Kōka 1) “Takeout Sushi Suggesting Ataka, from the series Women in Benkei-checked Fabrics”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1859 (Ansei 6), 6th month. “Three-color Shading Made to Order”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1859 (Ansei 6), 6th month. “Three-color Shading Made to Order”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Among the works on display in this section are five prints by each artist—selections from Kunisada’s Thirty-two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World (1820s) and Kuniyoshi’s Women in Benkei-checked Fabrics (about 1844). The title of Kunisada’s series refers to the popular form of fortune telling called physiognomy (ninsōgaku) that predicted the personality and future prospects of its subjects based on their facial features.

Utagawa Kuniyosh, 1852 (Kaei 5), 8th month. “Oh, ouch!” / Giant Octopus from the Nameri River in Etchū, from the series Auspicious Desires on Land and Sea. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Gift of Sue Cassidy Clark in honor of Sarah E. Thompson. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyosh, 1852 (Kaei 5), 8th month. “Oh, ouch!” / Giant Octopus from the Nameri River in Etchū, from the series Auspicious Desires on Land and Sea. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Gift of Sue Cassidy Clark in honor of Sarah E. Thompson. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Physiognomists often used magnifying glasses with imported Dutch lenses, like the one used for the series title on each print, to examine their clients’ faces. Kuniyoshi’s series, meanwhile, depicts fashionable young women dressed in fabrics with wide crisscrossing stripes, known in the present-day U.S. as “buffalo checks” and in Edo-period Japan as the Benkei pattern, after a legendary warrior.

Four Seasons in the City

The residents of Edo were proud of their city and enjoyed making excursions to its most famous scenic spots, choosing their destinations according to the season in order to enjoy sights of natural beauty such as snowfall or cherry blossoms, or annual events such as the “River Opening” at the beginning of the summer. The celebration featured a display of fireworks at the great

Ryōgoku Bridge, as well as temporary food stalls and other attractions along the river.

Artists like Kunisada and Kuniyoshi designed numerous views of fashionable city dwellers—especially beautiful young women—amusing themselves throughout the year, in a chic modern version of the theme of “Four Seasons” that had long been important in Japanese art.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1833 (Tenpō 4) “Clearing Weather, from the series Eight Views of Beauties”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Gift of L. Aaron Lebowich. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), 1833 (Tenpō 4) “Clearing Weather, from the series Eight Views of Beauties”. Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. Gift of L. Aaron Lebowich. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Riddles, Jokes and Secrets

Humor was an important element of Edo-period popular culture, and puns, wordplay and verbal and visual jokes of all kinds appear frequently in woodblock prints. Occasionally, humor was used to disguise social and political commentary that, in a more obvious form, would have been illegal under the strict censorship of the time.

Government regulations regarding what was and was not permitted in prints and printed books varied over time. The most extreme censorship occurred in the early 1840s under the so-called Tenpō Reform policies, which attempted a massive economic and social reorganization to counter the economic depression of the 1830s. In 1843, Kuniyoshi published The Earth Spider Generates Monsters at the Mansion of Lord Minamoto Yorimitsu—the subject was typical of his prints of warriors and monsters, but rumors quickly spread that it hinted discreetly at criticism of the current political situation. The print was banned and the blocks destroyed, but Kuniyoshi and his publisher escaped punishment because there was no clear proof of any wrongdoing. To this day, scholars argue about whether this work was a secret, illegal political cartoon.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1848 (Kōka 5/Kaei 1) “Actor Caricatures, from the series Scribbles on a Storehouse Wall” Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, about 1848 (Kōka 5/Kaei 1) “Actor Caricatures, from the series Scribbles on a Storehouse Wall” Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

From late 1842 until late 1846, prints of the two most important ukiyo-e subjects—actors and courtesans—were banned. They were eventually permitted again, provided that their names were not mentioned. Kuniyoshi responded by creating a series known as Scribbles on a Warehouse Wall, drawn in a deliberately crude style resembling graffiti. The prints showed famous actors, with a few scribbled words that helped to identify the roles and scenes. One sheet includes a cartoon version of dancing cats, again referencing the grand farewell performance of Onoe Kikugorō III as the cat monster in 1847.

This final section also includes a case of erotic books—a genre that was technically illegal, although the laws were not strictly enforced as long as sales were kept discreetly under the counter. Both Kuniyoshi and Kunisada illustrated numerous semi-secret erotic books in additional to their legal, publicly available illustrations, sometimes even signing the erotic works with special pen names. The first editions of these books are often very finely printed, using thick paper and special techniques such as metallic pigments and embossing. Like the surimono prints that they resemble, they may have been privately commissioned by wealthy and powerful patrons.

Sponsors

Patricia B. Jacoby Exhibition Fund and an anonymous funder.

Programs

A variety of programs complement Showdown! this fall, including a lecture on November 30 with internationally renowned and award-winning tattoo artist Chad Koeplinger, curator Sarah Thompson and artist Kenji Nakayama. Artist Demonstrations with Michael Shea of Redemption Tattoo are planned for November 12 and 15, exploring how contemporary tattoo artists incorporate

the designs of Japanese woodblock print artists in their creations. Additionally, free “Curated Conversations” on September 24 and November 12 offer the opportunity for visitors to drop in on a guided exhibition tour with Thompson.

Publications

Kuniyoshi X Kunisada

Kuniyoshi X Kunisada

Sarah E. Thompson, Curator, Japanese Art, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

With contributions by Masato Matsushima, Chika Kagami, Noriko Katsumori, Kazushi Kuroda, Yuiko Miwa, and Akira Tsukahara

262 pp. 180 illus.

10 ¾ x 9 ¼ in. (27.3 x 23.5 cm)

Hardcover

978-0-87846-847-8

$50.00 US | £35.00 U

September 2017

The rival ukiyo-e masters Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Utagawa Kunisada, the two best-selling designers of prints of the “floating world” in nineteenth-century Japan, meet in this gallery of kabuki actors, beautiful women, warriors, monsters, and more. Kunisada, the popular favorite during his lifetime, is distinguished by the realism and sensuality of his portraits, while Kuniyoshi’s dynamic action scenes and fantastic creatures are recognized today as precursors of manga and anime. Vivid full-color images, drawn from the unrivaled collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and accompanied by authoritative texts, invite viewers to explore the achievements of both artists and to enter into the world they bring to brilliant life.

The MFA and Japan

As the first major museum to collect and exhibit Japanese art in the US, the MFA has a long relationship with Japan, holding the first scholarly presentation of Japanese art in the US in 1892-93––the exhibition Hokusai and His School. Prior to the exhibition, in 1890, the MFA became the first museum in America to establish a Japanese collection and appoint a curator specializing in Japanese art. The MFA’s Asian Conservation Studio is one of only five such studios in the U.S. and is the oldest outside of Asia. Today, the Museum’s Japanese art collection is celebrated as the largest and finest outside Japan.

William Sturgis Bigelow, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, Edward Sylvester Morse, Okakura Kakuzō

William Sturgis Bigelow, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, Edward Sylvester Morse, Okakura Kakuzō

The extraordinary strength of the MFA’s Japanese collection is attributed to the foresight and enterprise of a small group of pioneering connoisseurs of Japanese art, including Edward Sylvester Morse, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, William Sturgis Bigelow and Okakura Kakuzō (also known as Okakura Tenshin). Bigelow became the department’s greatest benefactor, donating the majority of the Museum’s 4,000 Japanese paintings and more than 30,000 ukiyo-e prints—one of the largest collections of its type in the world. Among the tens of thousands of prints collected by Bigelow, the two artists whose works were by far the most numerous were Kuniyoshi and Kunisada. Following the formal donation of the Bigelow collection in 1911, subsequent gifts have increased the number of works by Hiroshige, so that he has now overtaken Kuniyoshi in the second place, but the “Bakumatsu

Big Three”—the three leading artists of the Utagawa school at the end of the Edo period—are still the stars of the collection in terms of quantity.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Avenue of the Arts at 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115

For more information, call 617.267.9300

www. mfa.org

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), is recognized for the quality and scope of its collection, representing all cultures and time periods. The Museum has more than 140 galleries displaying

its encyclopedic collection, which includes Art of the Americas; Art of Europe; Contemporary Art;

Art of Asia; Art of Africa and Oceania; Art of the Ancient World; Prints and Drawings;

Photography; Textile and Fashion Arts; and Musical Instruments.

Open seven days a week, the MFA’s hours are Saturday through Tuesday, 10 am–5 pm; and Wednesday through Friday, 10 am–10 pm. Admission (which includes one repeat visit within 10 days) is $25 for adults and $23 for seniors and students age 18 and older, and includes entry to all galleries and special exhibitions. Admission is free for University Members and youths age 17 and younger. Wednesday nights after 4 pm admission is by voluntary contribution (suggested donation $25), while five Open Houses offer the opportunity to visit the Museum for free. The Museum’s mobile MFA Guide is available at ticket desks and the Sharf Visitor Center for $5, members; $6, non-members; and $4, youths. The Museum is closed on New Year’s Day, Patriots’ Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas.