The Beginning of the World

– According to the Chinese –

A fabulous story of China narrated through Jade

Based on the works of art in SAM AND MYRNA MYERS’ collection,

six experts in Chinese history have written an exciting narrative that reveals the

universe of Chinese thought and its conception of the creation of the world.

BAUR FOUNDATION. GENEVA, November 11, 2020 – April 18, 2021

ASIAN ART MUSEUM OF NICE, May 8 – August 24, 2021

Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties, 11.9 cm

Highlights of the exhibition

under the direction of Jean-Paul Desroches

In every place, and in every time, the legitimate need to explain the origin of the world and its infinite vastness has been universal and by no means confined to the Judeo-Christian world. China, in its way, is no exception; it has written its own “Great Narrative” of the joinder of Heaven, Earth and Man – a narrative that can be deciphered through the prism of Chinese jades.

That is precisely what this exhibition sets out to do.

Cong with dragons in relief. Han dynasty, 19.4 × 10.3 cm

One of the pair of incense burners, jade, gilt bronze and silver. Han dynasty, 10.1 × 9 cm

Pushou. Han dynasty, 17.6 × 12.9 cm

Plaque in four sections with the animals of the four directions. Han dynasty, 20.5 × 34 cm

Footed cups on bases with the animals of the four directions, jade and gilt bronze.

Han dynasty, cups: 13 × 4.6 cm, bases: 2.2 × 13.3 cm

Belt hook, bronze with inlaid gold and silver Eastern Zhou dynasty, 7.3 × 17.8 cm

Part of a set of chimes, ritual instrument, with the animals of the four directions.

Han dynasty, the largest: 22 × 12 cm

Covered cup, jade and gilt bronze. Han dynasty, 17 × 10.1 cm

Bi with dragons. Han dynasty, 22 × 17.2 cm

The Heavenly Stone:

Jade in Ancient Chinese Culture

by Filippo Salviati

THE LATE NEOLITHIC:

HONGSHAN. ca. 4500-3000 BC.

The ancient Chinese worked a variety of soft and hard stones throughout the Neolithic period: it was, however, only from the mid to late fourth millennium BC that nephrite jade was exploited to an unprecedented level in a number of Neolithic cultures. This intensification of the use of jade accompanied the emergence of complex societies ruled by small elites whose members were also the intermediaries of a dialogue between the human world and the invisible forces that presided over it.

The ancient Chinese worked a variety of soft and hard stones throughout the Neolithic period: it was, however, only from the mid to late fourth millennium BC that nephrite jade was exploited to an unprecedented level in a number of Neolithic cultures. This intensification of the use of jade accompanied the emergence of complex societies ruled by small elites whose members were also the intermediaries of a dialogue between the human world and the invisible forces that presided over it.

Jade was then used exclusively to fashion symbols of earthly prestige and authority – such as personal ornaments and blades – and ritual artefacts associated with the religious sphere.

Thus, right at the beginning of Chinese civilization, and for about fifteen-hundred years, jade was regarded as a sacred material.

Graves found next to ritual structures

The graves found next to these ritual structures are stone-cist tombs containing intact or partly preserved skeletons adorned exclusively with jades.

Hongshan jades are carved in a variety

Hongshan jades are carved in a variety

of naturalistic and abstract shapes Images of birds with outstretched wings probably alluding to the realm of the skies and carvings of creatures with a serpentine body and an animal head. Regarded by Chinese scholars as the primeval form of the dragon, the mythical animal that in later times became associated with the emperor. LEFT: pendant in the form of a bird. Hongshan culture, 8.8 x 8.7 cm. RIGHT: Pendant in the form of a dragon. Hongshan culture, 20.3 x 20 cm.

The discovery, in one of the Niuheliang graves, of a large plaque carved as a bird with folded wings, placed behind the skull of the deceased, has prompted some Chinese scholars to view it as a possible antecedent of the phoenix of later times. IMAGE: Phoenix. Han dynasty, 12.9 × 6 cm

The discovery, in one of the Niuheliang graves, of a large plaque carved as a bird with folded wings, placed behind the skull of the deceased, has prompted some Chinese scholars to view it as a possible antecedent of the phoenix of later times. IMAGE: Phoenix. Han dynasty, 12.9 × 6 cm

Although the human figure in early Chinese art is rarely represented, the Hongshan culture provides notable exceptions to this rule. Anthropomorphic images carved in jade include intimidating seated figurines with a humanoid look, large slanting eyes, and bulky horn-like protuberances extending from the heads, these probably represent human beings dressed with ritual masks and hint at proto-shamanistic beliefs, while the standing figurines carved in reverent poses, with their hands raised in front of them, suggest the performance of ritual acts.

Although the human figure in early Chinese art is rarely represented, the Hongshan culture provides notable exceptions to this rule. Anthropomorphic images carved in jade include intimidating seated figurines with a humanoid look, large slanting eyes, and bulky horn-like protuberances extending from the heads, these probably represent human beings dressed with ritual masks and hint at proto-shamanistic beliefs, while the standing figurines carved in reverent poses, with their hands raised in front of them, suggest the performance of ritual acts.

Images from left to right: 1st and 2nd, ritual figurines, Hongshan culture, 10.6 × 5.6; 9.4 × 4.7;

3rd figurine: from Western Zhou: 9,1 × 3.7 cm.

THE LATE NEOLITHIC:

LINGJIATAN, ca. 3500-3200 BC

Contemporary to the late Hongshan period, that flourished in southern China, in Hanshan county, Anhui province. similarities in the jade artefacts suggest some form of long-distance contact between the Hongshan and Lingjiatan elites and possibly the partaking of common religious beliefs.

Contemporary to the late Hongshan period, that flourished in southern China, in Hanshan county, Anhui province. similarities in the jade artefacts suggest some form of long-distance contact between the Hongshan and Lingjiatan elites and possibly the partaking of common religious beliefs.

Tomb, Lingjiatan culture

ca. 3500-3200 BC

Aside from similarities, the Lingjiatan repertory of jade forms, decorative motifs and techniques of carving sets this culture apart, as demonstrated by the artefacts found in the graves of the eponymous site. The circle and the square were also two powerful symbolic forms for the jade-using Liangzhu culture.

The Liangzhu repertory of jades includes various types of ornaments, emblems of status, ceremonial blades and two peculiar objects that are considered ritual jades, given their non-functional nature: the Bi disc and the Cong tube

LEFT: Bi, Neolithic, early Bronze Age, Qijia culture, 37.6 cm

RIGHT: Cong, Liangzhu culture, 50.4 × 7.2 cm

Traditionally, and based on passages contained in texts of the 4th-3rd century BC, the Bi and the Cong have been interpreted as symbolic representations in jade of the circular Heaven and the square Earth.

BRONZE AGE:

SHANG AND ZHOU

With the advent of metallurgy and the emergence of the first state-level societies in the central China plains (Erlitou culture, ca. 1850-1550 BC), the role of jade as the chosen material to visually and symbolically express the power of the elite was challenged by the production of artefacts in bronze. The ritual vessels cast under the Shang, the first historical dynasty, became the paramount expression of the authority of the kings.

Eastern Zhou dynasty

Spring and Autumn period

Set of scholar’s knives, jade and gilt bronze, 26 × 4.7 cm

Eastern Zhou dynasty

Belt hook in the form of a rhinoceros, bronze

with inlaid gold, silver and turquoise, 13.3 × 5.5 cm

IMPERIAL CHINA:

QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES

The four and half centuries of the Qin (221-207 BC) and Han (206 BC – AD 220) dynasties defined the characteristics of the “classical” Chinese civilization and provided the political and cultural foundations for all later dynasties. The unifier of China and first ruler of the short-lived Qin dynasty, Qin Shi Huangdi (159-210 BC), was fully aware of the extraordinary scope of his achievements, so much so that he abandoned the designation of wang, king, used by the Shang and Zhou rulers, and proclaimed himself huangdi or “emperor”.

The four and half centuries of the Qin (221-207 BC) and Han (206 BC – AD 220) dynasties defined the characteristics of the “classical” Chinese civilization and provided the political and cultural foundations for all later dynasties. The unifier of China and first ruler of the short-lived Qin dynasty, Qin Shi Huangdi (159-210 BC), was fully aware of the extraordinary scope of his achievements, so much so that he abandoned the designation of wang, king, used by the Shang and Zhou rulers, and proclaimed himself huangdi or “emperor”.

The Western Han dynasty can rightly be considered as the highest peak reached by jade craft in ancient China. . There are two main reasons behind this phenomenon. The first is “political” and is related to the sumptuary regulations introduced by Wendi, who welcomed the ideas advanced by Jia Yi (200-168 BC) — a celebrated writer, poet and statesman of the Han period — in a number of memorials submitted to the throne. Jia Yi “… proposed a new sumptuary code regulating a range of luxury goods from apparel to accessories to ritual wares. This sumptuary system was designed to bolster the authority of the imperial throne and to distinguish members of the Han government and the imperial family from other elites.”

Belt hooks, Han Dynasty

Left: Belt Hooks with dragon, jade and gilt bronze, 13.3 x 5.5 cm

Right: Belt Hook with animal of the four directions,

jade and bronze with inlaid gold and silver, 14.5 x 3 cm

Box, jade and gilt bronze. Han dynasty, 4 × 8.7 cm

Box, jade and gilt bronze. Han dynasty, 4 × 8.7 cm

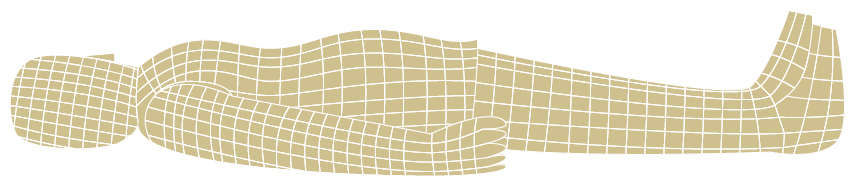

Lavish burials

The Xuzhou tombs have also yielded examples of the most extravagant type

of funerary jades created in the Western Han: the jade suits formed by thousands of

small plaques sewn together and used to dress the corpse at the moment of burial.

These suits started to be produced under the reign of emperor Wen

and were strictly reserved for members of the imperial family.

Part of a funerary suit. Han dynasty, 75 × 59 cm

Pair of covered jars, glass. Han dynasty, 17.1 × 10.4 cm

Eating jade

Eating Jade, letting the body absorb its substance was thought to help in extending one’s life. Jade was believed to be an ingredient of the diet of the xian, or immortals, who dwelled on top of inaccessible sacred mountains or in their remote islands in the eastern sea.

Eating Jade, letting the body absorb its substance was thought to help in extending one’s life. Jade was believed to be an ingredient of the diet of the xian, or immortals, who dwelled on top of inaccessible sacred mountains or in their remote islands in the eastern sea.

Finely decorated jade cups, sometimes embellished with gilt-bronze mountings were not just luxurious objects appropriate to the status of their owners.

Footed cup

jade and gilt bronze

Han dynasty

13.8 × 5.2 cm

Heaven, the other Half of the Earth

by Jean-Paul Desroches

The first morning of the universe as described in the Huainanzi

“There was a beginning.

There was a time that preceded the beginning.

There was a time before the time that preceded the beginning.

There was Being.

There was Non-Being.

There was a time which preceded the Non-Being, which was not yet the Non-Being.”

*This explanation is contained in the first three chapters of the Huainanzi, the handbook of Prince Liu An (179–122 bc), uncle of the most powerful of the Han emperors, Wudi (r. 141–81 bc).

Before this profusion of origins, before Heaven and Earth were formed, the elusive, invisible, inaudible, impalpable, immediate presence, the Dao, matrix of the universe though not a demiurge, began in the immense void. The vast void engendered space and time. Space and time engendered the “vital breath,” the qi.

Before this profusion of origins, before Heaven and Earth were formed, the elusive, invisible, inaudible, impalpable, immediate presence, the Dao, matrix of the universe though not a demiurge, began in the immense void. The vast void engendered space and time. Space and time engendered the “vital breath,” the qi.

In this silent, unfathomable void, without form, the qi gradually penetrated. Everything was teeming with the desire to be born, all was yet formless. That which was light and subtle dispersed to form Heaven; the heavy and turbid coalesced to form Earth. It was easy for that which was light to converge, but difficult for the heavy elements to coalesce. Therefore, Heaven was formed before the Earth. The conjoined essences of Heaven and Earth produced yin and yang, giving rise to the Ten Thousand Things which, since then, animated by the qi, have never stopped reproducing.

This introduction, which presents the Dao as a mysterious and active reality engendering the cosmos, time and the Ten Thousand Things, fits surprisingly well with current theories regarding the formation of the universe.

From astrology to astronomy

Most researchers today agree that the emergence of scientific astronomy dates back to the Warring States period (454-222 bc). . But there was a long period of gestation, during which science struggled to shake itself free from astrology. Three prominent figures stand out in ancient history: Wu Xian, Gan De and Shi Shen.

Gan De and Shi Shen worked as advisers to the princely courts. The involvement of scholars at the heart of the State is a constant throughout the history of China. Under Emperor Wudi there were entire teams of celestial observers, timekeepers and calendar specialists who worked day and night in the service of the State.

Gan De and Shi Shen worked as advisers to the princely courts. The involvement of scholars at the heart of the State is a constant throughout the history of China. Under Emperor Wudi there were entire teams of celestial observers, timekeepers and calendar specialists who worked day and night in the service of the State.

What is astonishing is not only the diversity of the celestial bodies that were recorded, but also the detail and accuracy of the readings. All those auguries were directed towards the conduct of state affairs. The Heavens were a complex system animated by cyclical movements and, at the same time, a mirror that reflected, announced and anticipated what might happen on Earth. Heaven, at that time, was considered the other half of the Earth.

The Wu xing zhan is the most complete compendium of information on the planets. Although it is presented as part of the theory of the “Five Elements” – each planet being associated with an element onto which a system of correspondences has been grafted: the work, has a sound scientific basis. To obtain such detailed information involved regular observations over tens or even hundreds of years.

This unrelenting determination that runs through the history of ancient China and this amazing cornucopia of discoveries confirm the unique status attributed to Heaven. China found its place under Heaven; it was the role of the Son of Heaven to make the Earth the other half of Heaven.

Earth, the other Half of Heaven

by Jean-Paul Desroches

The first two royal dynasties, the Xia and the Shang (c. 2205-1045 BC), tried to place the unknowable at the heart of the State. The Zhou (1045-256 BC) attempted to impose rites and the Warring States (475–221 BC) sought to conceive cosmological thought. From then on, Man and nature were to reign as one, to establish an absolute equivalence between the functioning of the cosmos and that of human society, identifying the role of the sovereign with the principle of the universe of which he is the guarantor. The sovereign was known as the “Son of Heaven.” His mandate was not due to the mere fact of family lineage, or even of conquest, but was granted by Heaven itself. Thus, with him, Heaven came down to Earth.

To govern implied being in harmony with the universe, and this harmony was achieved through appropriate rituals. The sovereign, mandated by Heaven, assisted Heaven by dint of his virtue and thus contributed to the smooth running of the universe.

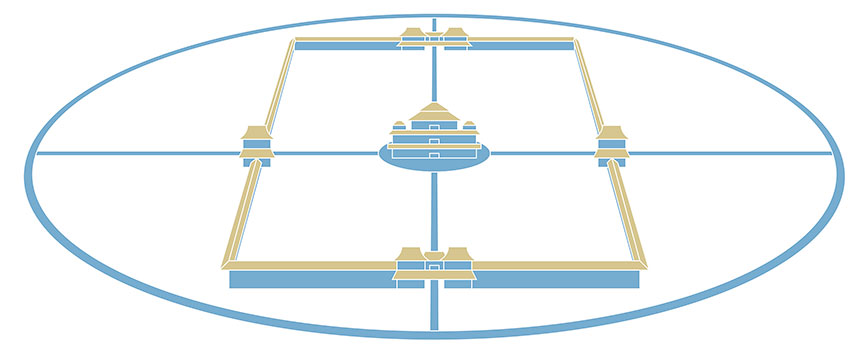

The mingtang

The mingtang was a particularly auspicious place for the Sovereign to exercise his unique mandate. Inside this building he was in communion with the cosmos – its design, based on the circle and the square, the two basic forms representing Heaven and Earth, had already been used to adapt the banliang, the Qin currency that had been adopted by the Han. This symbolic constancy is also found in jade, particularly in two emblematic objects, the bi disk and the cong cylinder, which have been present since the Neolithic period in many burial sites.

Plan of a mingtang, Chang’an, 4 A.D.

Design by Kanta Desroches

Qiniandian, “Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests,”

Aerial view, 1938

The combination of the celestial circle and the terrestrial square, associated with the four cardinal directions, remained a recurrent principle that was systematically applied during the last three dynasties, the Yuan (1271-1368), the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911).

The Animals of the Four Directions

by Laure Schwartz-Arenales

The East is represented by wood, its constellation is the Green Dragon; the West by metal, its constellation is the White Tiger. The South corresponds to fire, and has as constellation the Red Bird; the North is connected with water, its constellation is the Black Tortoise. Heaven by emitting the essence of these four stars produces the bodies of these four animals on earth. Of all the animals they are the first, and they are imbued with the fluids of the Five Elements in the highest degree. Wang Chong (27-97?) Discourses Weighed in the Balance (Lunheng)

The East is represented by wood, its constellation is the Green Dragon; the West by metal, its constellation is the White Tiger. The South corresponds to fire, and has as constellation the Red Bird; the North is connected with water, its constellation is the Black Tortoise. Heaven by emitting the essence of these four stars produces the bodies of these four animals on earth. Of all the animals they are the first, and they are imbued with the fluids of the Five Elements in the highest degree. Wang Chong (27-97?) Discourses Weighed in the Balance (Lunheng)

Four fabulous astral beasts have watched over the four cardinal points of the world since the beginning of the Celestial Empire. Infused with yuanqi, the primordial breath, from the axis of the sky, the Pole Star and the Northern Bushel, our Big Dipper, with its emblematic Yellow Unicorn (Qilin), associated with the center and the earth, the Green Dragon (Qinglong), the Vermilion Bird (Zhuque), the White Tiger (Baihu) and the Black Tortoise – or Black Warrior – (Xuanwu), each govern a season and a palace comprising seven of the constellations of 28 lunar mansions (xiu) of the celestial equator.

The Green Dragon

(Qinglong)

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

The azure-scaled Green Dragon is heir to a long history and an astounding array of images, as we see in the jade pendants and masks of the Neolithic cultures of Hongshan and Liangzhu. Associated with spring, wood, yang and the seven lunar mansions of the Eastern Palace.

This Cosmic Guardian, among its many avatars, appears as a manifestation of the dragon. Source of all metamorphoses, this benevolent creature is venerated, depending on the place and its function, as master of the waters, of the family of dragons of the wells, dilong ; as the rainmaker, moving like a fish in underground waves; or as master of the air, of the family of dragons of the sky, shenlong, sprung from clouds, filled with the primordial breath.

Its prodigious skills were linked to the destiny of emperors, who revered the dragon as their ancestor, from the first mythical ruler, the Yellow Emperor Huangdi and his illustrious descendants, Yu the Great or Liu Bang, founders of the Xia and Han dynasties. Throughout the reigns of the Sons of Heaven, the rites and the prestige of the imperial court, its costumes and its etiquette, were all used to proclaim the ancestry of the divine dragon.

The Vermilion Bird

(xiu)

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

The blazing Vermilion Bird personifies the seven lunar mansions of the Southern Palace over which it reigns (the Well, the Spirits, the Willow, the Seven Stars, the Spread Net, the Wings, the Chariot); it is linked to fire, to yang and to summer.

It has the head of a rooster, the neck of a mandarin duck, the dazzling plumage of a peacock, a pheasant’s tail, the powerful flight of a swan, the legs of a crane and its melodious song delights all who hear it.

Although it lives in faraway regions and on heavenly islands, often close to the sun, the fenghuang, as its syncretic body implies, is first and foremost the representative on earth of all feathered creatures, both real and imaginary.

The Black Tortoise

or Black Warrior (Xuanwu)

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

Guardian of the North, this hybrid creature, sometimes known as the Black Warrior (Xuanwu: xuan, “black”, wu, “warrior”), governs the seven lunar mansions of the Northern Palace (the Big Dipper, the Ox, the Maid, the Void, the Roof, the Encampment, the Wall); it is associated with water and winter.

In astrological speculations that developed during the Warring States period, the Black Warrior played a primordial role in the control of human destiny thanks to its location in the northern quarter of the zodiac, where the Big Dipper and the North Star, as well as the asterisms governing birth, death and longevity, are found. The Black Warrior’s essential mission is to block the path of evil spirits which, according to geomantic beliefs, are particularly present at the gates of the northern regions.

The White Tiger

(Baihu)

Detail from the Bi with the animals of the four directions. Six Dynasties

In the western quarter of the world, the White Tiger guards the seven lunar mansions of the Western Palace (the Legs, the Bond, the Stomach, the Pleiades, the Net, the Beak, the Triad); it is associated with yin, metal and autumn. A sacred and majestic animal, king of the forests, mountains and wild beasts, it has been an object of veneration since ancient times.

The White Tiger defends against demons and drives away disease with the courage and fighting spirit that have made it the ensign of warriors. Thanks to these heroic qualities, the White Tiger complements the dragon to form the oldest and most widely depicted pairing among the four cardinal deities.

Other guardians of the world

Bixie, jade with inlaid gold wire. Han dynasty, 9.9 × 17.7 cm

A whole family of chimeric and psychopomp creatures endowed with supernatural powers belongs to the same “atlas” of the universe and that same creative and spiritual profusion that came into Being with the Genesis. In the form of statuettes, like talismans, the bixie, those composite creatures whose powerful dragon heads rise from the bodies of winged animals, roar to frighten all demons of earth and heaven.

The Phoenix

Phoenix, gilt bronze. Tang dynasty, 14 × 12.5 cm

The phoenix sometimes manifests itself to virtuous men as the herald or witness of a peaceful reign; it is associated with the person of the Empress and, along with the dragon, forms a couple that glorifies the imperial dynasty. The two together also metamorphose into a celestial mount to guide the deceased in their peregrinations toward immortality.

Immortality and Jade

The aspiration to immortality, coupled in the Han period with the desire to be surrounded after death by objects in keeping with one’s status, made jade a highly suitable material for portraying the emblems of the four directions, which were carved with impressive dexterity as reliefs or in the round. Pushou tomb-door knockers, ritual ornaments, bi, belt hooks, ritual cups to receive the drink of the immortals, seals and mat weights, all glorified the daily life and beliefs of the departed, over whom the four sacred animals kept eternal watch, in virtuoso complicity with the incandescence of that hard stone.

Immortals, Mortals

and the Quest for Immortality

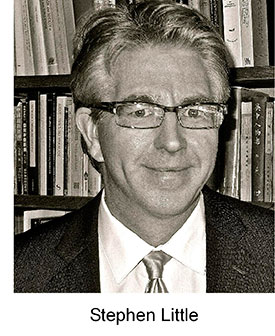

by Stephen Little

In China Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism are known as the “Three Teachings” (san jiao). Daoism is both a philosophy and a religion, and understanding the history of Daoism is key to understanding Chinese culture, for Daoism has influenced such varied disciplines as cosmology, medicine, cooking, calligraphy, painting, military strategy, and even Chan (Zen) Buddhism.

In China Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism are known as the “Three Teachings” (san jiao). Daoism is both a philosophy and a religion, and understanding the history of Daoism is key to understanding Chinese culture, for Daoism has influenced such varied disciplines as cosmology, medicine, cooking, calligraphy, painting, military strategy, and even Chan (Zen) Buddhism.

At the heart of Daoism is the Dao (meaning a “road” or “way”), conceived paradoxically as an empty void simultaneously pregnant with all of existence. Beyond time and space, the Dao is the source of all things.

From the Dao was spontaneously born qi (energy or breath) and the forces of yin and yang, whose interaction governs all celestial and terrestrial processes and gives birth to the Five Elements (Phases), from which all things are made. Daoism first emerged as a philosophy, attributed to the sage Laozi, an archivist and diviner active at the Eastern Zhou dynasty court in the late 6th century bc. In the Eastern Han dynasty (1st – 2nd centuries ad), Daoism transformed into a religion.

Immortals

Immortal riding a bixie

Han dynasty, 9,5 × 16 cm

For mortals there is a fundamental distinction in Daoism between gods and immortals. Daoist gods are of two basic types. The highest gods, such as the Three Purities (Sanqing) – the Celestial Worthy of Primordial Beginning (Yuanshi tianzun), the Celestial Worthy of Numinous Treasure (Lingbao tianzun), and the Celestial Worthy of the Dao and its Power (Daode tianzun, the deified Laozi) – are the Dao’s purest emanations, made up of the most refined qi or pneuma.

Each of the Three Purities rules over its own heaven; these are respectively known as Jade Purity (Yuqing), Highest Purity (Shangqing) and Great Purity (Taiqing). The highest of these is Jade Purity. These deities put a human face on the Dao, and help make visible and comprehensible what cannot easily be perceived or imagined.

Immortals, on the other hand, almost always begin their lives as ordinary human beings who, often with the benefit of a teacher who has transcended the boundaries of yin and yang, achieved union with the Dao. These figures, both male and female, are revered for their spiritual powers and their ability to work miracles, and are worshipped as divine saints.

The quest for immortality

The Chinese quest for immortality has a long history,

extending well into the Bronze Age. Within the Daoist

Burial in Jade

In the Neolithic period, jade was more than a mere medium; it became a vector reflecting the concerns of the ruling elite who decided they wanted it to be associated with their burials. Two types of objects were produced in abundance: bi, which were circular, and cylindrical cong, both of which were destined for a lengthy posterity.

In Sidun, in tomb no. 3, for example, 31 cong and 24 bi were found. The deceased was literally buried in jade.The bi were usually placed on the body while the cong, some of which could be as tall as 40 cm, were placed around it.

Archaeological and textual evidence amply demonstrates the belief that jades buried in and around the corpse would preserve the body in the afterlife.

A jade suit sewn with gold wire (jinlü yuyi) was the supreme mode of burial in the Han funerary ritual. The jade shroud sewn with gold wire was the emperor’s prerogative; kings were clad in a jade garment sewn with silver.

The shroud of Prince Liu Sheng, Mancheng, Hebei, 113 bc

Design by Kanta Desroches

Funerary face covering Western Zhou dynasty

In some cases, the faces were also covered with jade masks

replicating the facial features and sewn onto a textile

Lian in the form of the island of the Immortals

Glazed terracotta. Han dynasty, 30 × 22 cm

The money tree

Yaoqianshu, the money tree was a burial tradition in southwest China, popular from the 1st to the 3rd century ad. It consisted of a molded terracotta base into which the trunk of a cast and hammered copper alloy tree was inserted. Its highly charged decoration is characterized by an elaborate iconography.

Yaoqianshu, the money tree was a burial tradition in southwest China, popular from the 1st to the 3rd century ad. It consisted of a molded terracotta base into which the trunk of a cast and hammered copper alloy tree was inserted. Its highly charged decoration is characterized by an elaborate iconography.

The example in the Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques de Nice is the only one of its kind in a French collection. Its base is in the form of a mountain with a frieze of elephants and supernatural beings.

The mountain is surmounted by an immortal riding a ram and holding a cylinder in which the tree trunk is planted. On it are five bears and five tiers of four branches.

Each branch is finely decorated with flowers, figures, animals and fantastic creatures cavorting around coins.

IMAGE: Money tree, copper alloy and terracotta. Han dynasty, 158.8 × 40 cm

Nice, Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques, acc. no. 99.5.1

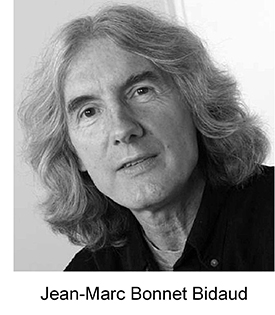

Celestial Questions

by Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud

From the first dynasties, Heaven was at the center of the Chinese world and astronomical knowledge acquired a political dimension. As has often been pointed out, the emperor, dignified with the name Tianzi (son of Heaven), was the holder of the celestial mandate, the Tianming (天命), which made him responsible for maintaining harmony between the Earth and the Sky.

From the first dynasties, Heaven was at the center of the Chinese world and astronomical knowledge acquired a political dimension. As has often been pointed out, the emperor, dignified with the name Tianzi (son of Heaven), was the holder of the celestial mandate, the Tianming (天命), which made him responsible for maintaining harmony between the Earth and the Sky.

In order to be awake to any celestial changes that might have an influence on the empire, he maintained a team of astronomers, mathematicians, astrologers, and guardians of the clepsydra, etc … within the imperial observatory which was, in this way, exactly similar our modern research organizations. These Chinese astronomers became the “chroniclers of the Sky”, meticulously recording unusual and exceptional phenomena such as star explosions, comets, eclipses, and sunspots. They created spectacular archives, which modern astrophysicists still draw on with delight, occasionally finding the roots of what they observe today.

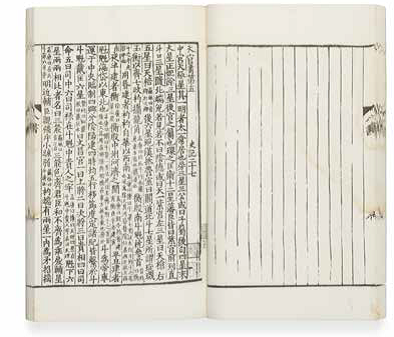

Thousands upon thousands of years of astronomical observations were thus carefully recorded and preserved, a unique achievement anywhere in the world, and in complete contrast with the long eclipse that the European world experienced for more than fifteen centuries, when the religious precepts of monotheism imposed a brutal separation between man and the rest of the universe. In monotheism, Heaven was the domain of God and it was said to be perfect and immutable. It was therefore unthinkable to question its nature or to speculate upon any phenomena that might occur there. IMAGE: Shi ji or “Historic Memoirs”, chap. 27: Tianguanshu (“Book of Celestial Off icers”) Sima Qian’s treatise on astronomy

Thousands upon thousands of years of astronomical observations were thus carefully recorded and preserved, a unique achievement anywhere in the world, and in complete contrast with the long eclipse that the European world experienced for more than fifteen centuries, when the religious precepts of monotheism imposed a brutal separation between man and the rest of the universe. In monotheism, Heaven was the domain of God and it was said to be perfect and immutable. It was therefore unthinkable to question its nature or to speculate upon any phenomena that might occur there. IMAGE: Shi ji or “Historic Memoirs”, chap. 27: Tianguanshu (“Book of Celestial Off icers”) Sima Qian’s treatise on astronomy

In China, by contrast, the Earth and the Sky were the yin and the yang – two complementary facets of one reality and a single object of observation and study. It is these very different visions between Europe and China that led, on the one hand, to an utter dearth of astronomical and scientific enquiry right up to the sixteenth century while, on the other, not only astronomy but also the sciences and technology were practiced and developed without constraint for forty centuries.

The geographers of Heaven

The Chinese astronomers were particularly meticulous observational astronomers and mappers of the sky. They drew up a very complete celestial inventory, first in the form of catalogues of stars and then in the form of surprisingly modern celestial charts.

Exact positioning on the celestial sphere was crucial in the Chinese tradition because each part of the empire was represented in the sky and the appearance of an unusual celestial phenomenon gave rise to a divinatorial interpretation with important political consequences for the world below.

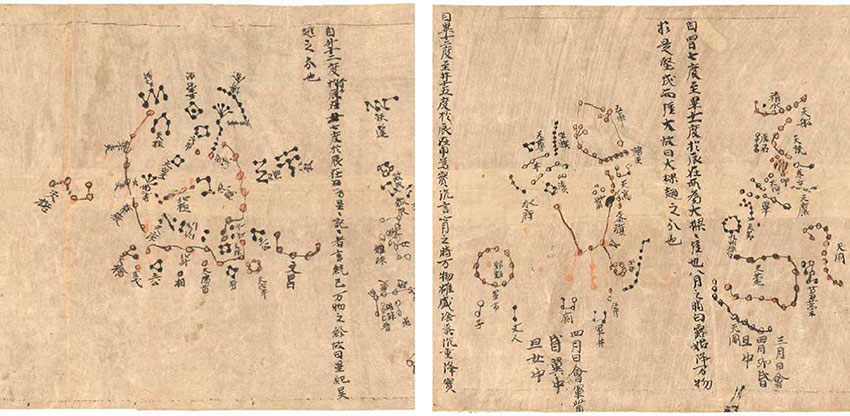

Dunhuang Celestial map. Northern hemisphere, 649-684

Dunhuang Celestial map, Northern hemisphere. Manuscript on paper, Dunhuang, Gansu, beginning of the Tang dynasty (649–684), London, British Library, Or.8210 / S3326

Historians of the Sky

For a long time, Europe in particular considered space and time as two separate concepts. In China, by contrast, historicity is the basis of everything. The succession of historical terrestrial facts was recorded dynasty after dynasty in increasingly voluminous encyclopedias, with astonishing continuity over thousands and thousands of years. Time was therefore totally integrated into their conception of the world. So much so that, by the 2nd century before the modern era, in the cosmology of Prince Liu An’s Huainanzi (-138 BC), the concept of “universe” is designated by the term “yuzhou – 宇宙”, literally “space-time”, a surprisingly modern notion that did not really emerge in Europe until Einstein’s work on Relativity!

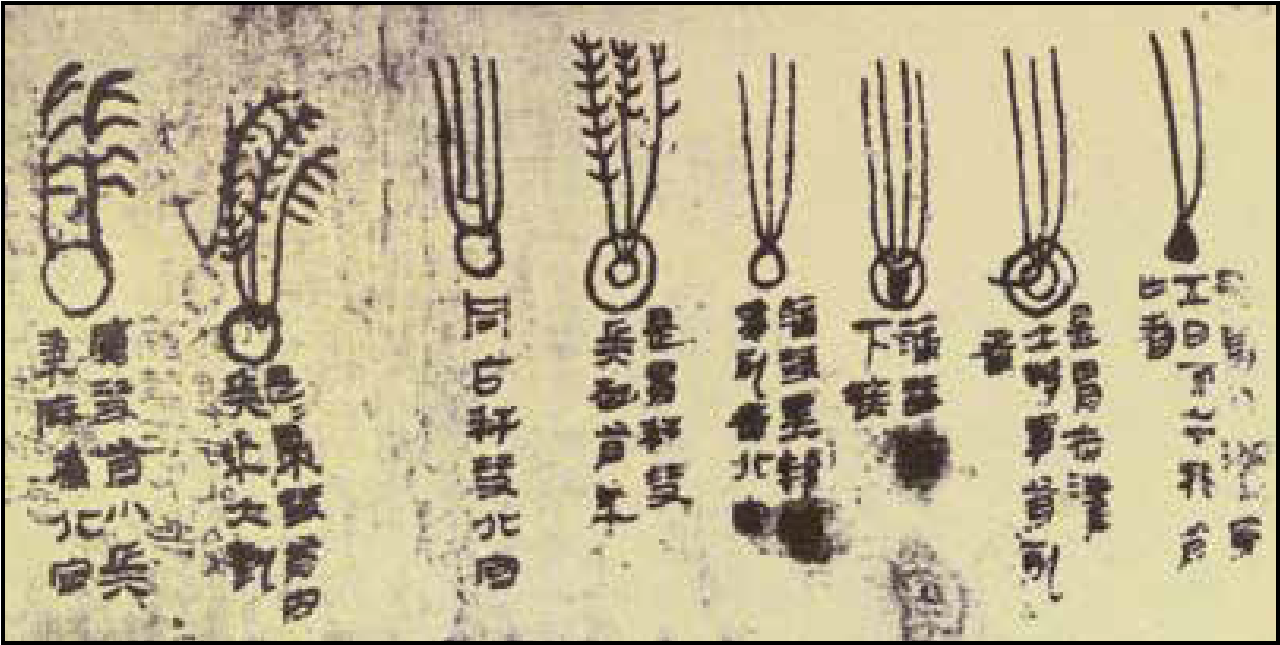

Comets had particularly fascinated Chinese astronomers since ancient times, as was shown in an exceptional archaeological document dating back to the year -167 BC. Given the relative rarity of comets, it must have been the result of observations made over several centuries during the Zhou dynasty. IMAGE: Comet catalog, observations collected over several centuries during the Zhou period

Comets had particularly fascinated Chinese astronomers since ancient times, as was shown in an exceptional archaeological document dating back to the year -167 BC. Given the relative rarity of comets, it must have been the result of observations made over several centuries during the Zhou dynasty. IMAGE: Comet catalog, observations collected over several centuries during the Zhou period

For modern astronomy, the most valuable Chinese observations are those of star explosions. These explosions, which mark the end of the life of a massive star, are called “supernovas” today.

China was thus the only country that had painstakingly plotted both the geography and the history of Heaven. Yet, the detailed nature of its findings was still largely unrecognized in Europe, notably due to a historic misunderstanding.

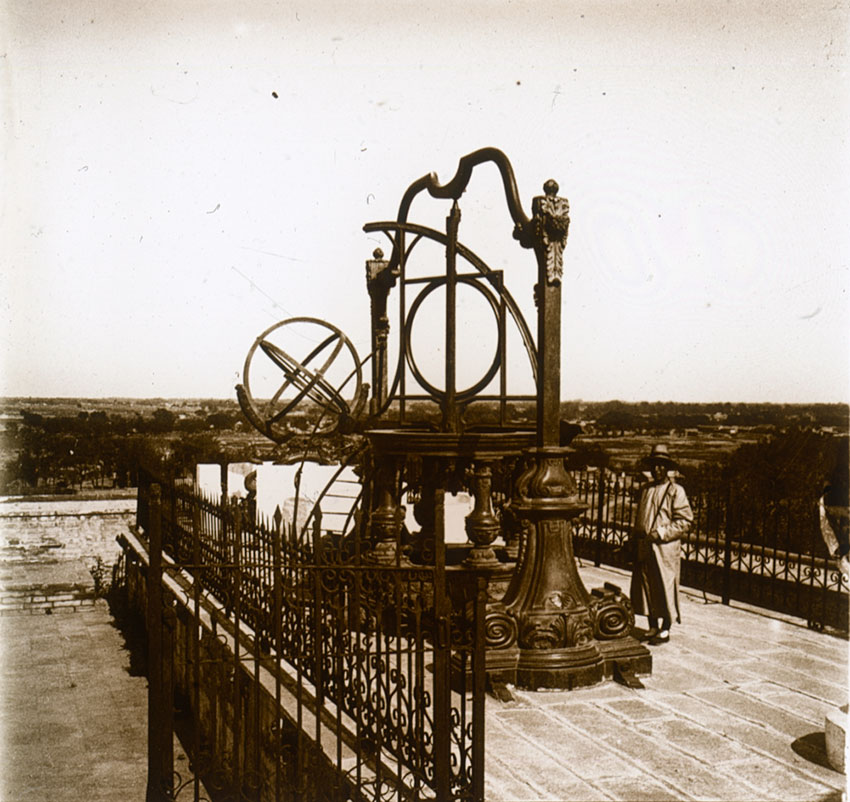

Beijing observatory

Bernard-Kilian Stumpf ’s theodolite (1715) and Ferdinand Verbiest’s armillar y sphere (1673),

Beijing Observatory (photograph by Joseph Rastoul, 1909)

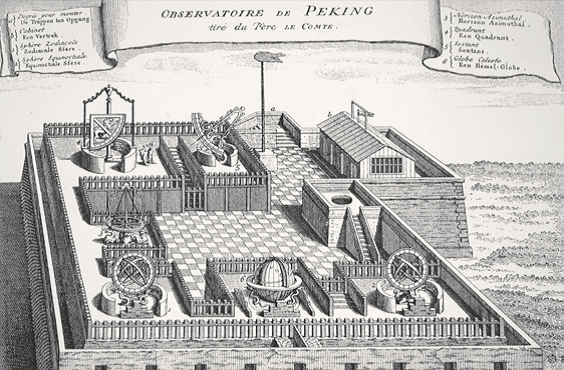

When the first Jesuit, Mateo Ricci, entered China and visited the imperial observatory of Nanjing in 1600 ad, he was dazzled by what he saw and reported “we find mathematical machines made of cast iron, which are worth seeing for their great size and beauty. We have certainly never seen or read about anything like them in all of Europe.” He had discovered instruments of astonishing modernity in both their impressive size and their design. IMAGE: Beijing observatory, built between 1669 and 1673, engraving from « Les Six machines de l’observatoire de Pékin installées par le père Ferdinand Verbiest », in Louis Le Comte, Nouveaux Mémoires sur l ’État Présent de la Chine, Paris, Jean Anisson, 1696-1697.

When the first Jesuit, Mateo Ricci, entered China and visited the imperial observatory of Nanjing in 1600 ad, he was dazzled by what he saw and reported “we find mathematical machines made of cast iron, which are worth seeing for their great size and beauty. We have certainly never seen or read about anything like them in all of Europe.” He had discovered instruments of astonishing modernity in both their impressive size and their design. IMAGE: Beijing observatory, built between 1669 and 1673, engraving from « Les Six machines de l’observatoire de Pékin installées par le père Ferdinand Verbiest », in Louis Le Comte, Nouveaux Mémoires sur l ’État Présent de la Chine, Paris, Jean Anisson, 1696-1697.

There is nothing surprising about China’s return to the forefront of science and technology today. It is not the emergence of a developing country but the rebirth of a great scientific civilization after a mere eclipse.

It All Started in Ascona in 1966

The story of how Sam and Myrna Myers created their collection

told by Sam Myers himself

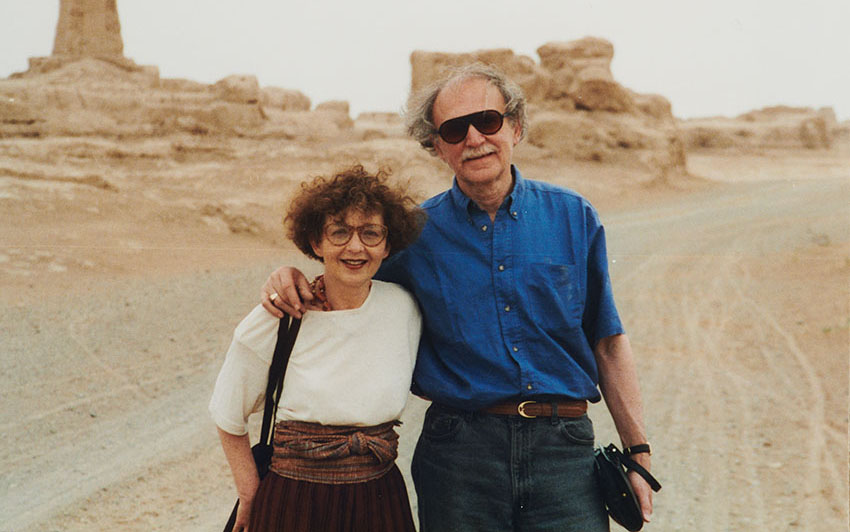

Sam et Myrna Myers, Dunhuang, 1996

“Myrna and I were unlikely collectors of Asian art. We were first generation Americans whose parents and grandparents came uneducated and penniless from Russia and Poland. We did not grow up surrounded by art or books. We were the first members of our families to go to a university, where our thirst for knowledge and appreciation of beauty developed”.

“Soon after we were married, we shared a taste for collecting objects which appealed to us – old ceramics, metalwork, an unusual mirror, a leather-bound album of 19th-century photos… whatever struck us. When we moved to Paris, that approach continued and became a passion. We would venture out each weekend within the radius of Paris to find new antiques with no particular focus, merely a search for things we liked. In some strange way, Chance took over. Our search for discovery led to many paths which appeared to end with closed doors, but our curiosity generally caused us to walk through those doors to see what was on the other side”.

It started in Ascona – purely a chance encounter

“We were headed to Locarno in driving rain on the Autostrada del Sole, where I remembered having seen a hotel called La Romantica, which I thought would make Myrna very happy. It was our first trip after our arrival in Europe in 1966. When we got there late at night, I realized that the hotel was in Lugano and not Locarno, 25 miles away. The next morning, disappointed by the town, we asked if there were any antique shops nearby and were directed to Ascona, a small town 5 miles away which we were told had many shops”.

Discovering Casa Serodine and Dr. Rosenbaum

“Across from the main square, we saw a sign: Casa Serodine. It was a grand 17th century building facing the Cathedral. It had a huge carriage entrance behind which there was a large courtyard filled with cabinets holding all kinds of antiques – Greek, Roman, Persian, Renaissance, etc. Each piece had a small card identifying it and an inventory number, but no prices. Myrna and I disagreed”.

“She said it was clearly a museum and I said it had to be an antique shop. I wanted to go in to ask, but Myrna said Please don’t. I will be so embarrassed. I was headstrong and went in. It was indeed an antique shop and the young woman graciously suggested that we visit all four floors”.

“She said it was clearly a museum and I said it had to be an antique shop. I wanted to go in to ask, but Myrna said Please don’t. I will be so embarrassed. I was headstrong and went in. It was indeed an antique shop and the young woman graciously suggested that we visit all four floors”.

“We were stunned by what we saw. Real antiques which were for sale – parts of the past which you could own – which you could live with”.

“After we finished exploring the whole gallery, the young woman, Barbara Lerch, asked if we would like to meet the owner, Dr. Rosenbaum. We, of course, said yes and followed her to an office at the far end of the shop, where he sat behind his desk surrounded by what seemed like an endless collection of books and artifacts”.

Dr. Wladimir Rosenbaum at Casa Serodine,

Dr. Wladimir Rosenbaum at Casa Serodine,

Ascona, 1984

“He was a short, bald man who wore glasses halfway down his nose so he could see over them, dressed in a wrinkled suit and tie, with a welcoming smile. Barbara told him that we were a young couple living in Paris who were interested in collecting. He extended his hand, clasped mine, and said, Goodbye. After having been taken aback, we came to understand that that was his way of saying Hello in English”.

“We told him how excited we were to find that it was possible to acquire real antiques, but I explained that I, as a young lawyer, could not conceivably buy anything, since I was just starting out. His response surprised us: he said, How much can you spend? Completely flustered, having no idea of what to say, I stuttered, I, I don’t know, I guess $20. To my surprise, he called out, Fritz! Bring me the box of Tanagra heads. After a few moments, Fritz appeared carrying a box with small terracotta heads which we learned were made in Greater Greece, probably in Sicily, in the 5th century bc. From behind his desk, Dr Rosenbaum smiled and simply said, Any one you want, $20. We couldn’t believe what was happening and avidly went through the pieces before us, ultimately choosing four of them. We had suddenly ventured into the world of collecting real art objects”.

Return to the source

“Every summer thereafter, for many years, we returned to Ascona, in search of some new antiquity which we would choose, after approval and guidance from Dr. Rosenbaum, who became our mentor and very dear friend”.

“He must have taken a liking to us, because he invited us to join him for dinner several times at home. He and his wife Sybille lived on the second floor of a house in the hills overlooking the town. Much to our surprise, he had very few art objects at home, but I do remember a beautiful Tang lady in flowing robes and a striking stylized bronze hand on the mantelpiece in the living room. I saw him holding the same hand in a Swiss television documentary celebrating his life”.

“Our path to collecting antiques with Dr Rosenbaum followed the classic route, with each trip to Ascona we reached further – a black granite Egyptian head, Greek pottery and sculpture, Roman bronzes, Luristan bronzes, and eventually Tang ceramics and a Japanese bodhisattva”.

“We pursued objects whose beauty and power arrested us, whatever gave rise to our excitement of discovery and opened a path to learn about new fields”.

“Our venture into Chinese art also occurred with the aid of Chance. It started in 1968 in Ghent, but that is another story which is told in our first catalogue.

First encounter with Jade

“We became immersed in Chinese art. It began with an interest in 17th century blue and white porcelain, and moved backward through Ming, Song and Tang ceramics and outward toward Japanese and Korean wares. At one point in the early 1970s, Myrna asked me to look for something different when I travelled on business (I generally took a day or two to visit museums and antique shops wherever I went). I asked what she might be interested in and her reply was I don’t really know, maybe sculpture or perhaps jade”.

“As it turned out, I had a trip to the United States scheduled and planned to visit my family in Philadelphia, which gave me the chance to visit an old antique dealer who had a small shop in the center of the city in which he sold Asian and Middle Eastern art. After looking through the pieces on offer, some of which appealed to me very much, I asked him if he had any jade. Mr. Fiorillo was a gruff older man who had been in his gallery for over fifty years and was not interested in small talk, despite the fact that I had known him for quite some time. He said, Yes, I have a box full of that stuff, but I don’t put it out because people steal it. If you want it, you have to take the whole thing”.

“Despite that less than inviting invitation, I replied, Yes, I would very much like to see it. After rummaging under the counter, he brought forth something that looked like a shoe box filled with sixty jades of various sizes, shapes and colors. I must admit that I could not figure out anything about the pieces I was looking at”.

“I had never looked at jade carvings before. I had never looked at jade carvings before, and had

no knowledge, except that I found them beautiful and fascinating. After a relatively lengthy discussion, where he would not budge from his position of selling all or nothing, he agreed that he would send them to me in Europe so that Myrna could see them. If she liked them, we would buy the lot. When they arrived, we were very excited, but we knew no more than we did when I was in Philadelphia. At the time, we were staying in Ascona, so we headed to Casa Serodine to seek Dr. Rosenbaum’s advice. Unfortunately, he was not able to help us, because he did not have any more background in jade than we did. So we turned to Mr. Kohler, a Tibetan art dealer whose gallery was on the lakefront. He too could be of no help. As a last resort, we went to the jeweler in Ascona to ask if he could identify the pieces. All he could tell us was that they were made of good quality jade, but he knew nothing of earlier pieces because he only worked with modern jade”.

“Not discouraged, we were determined to learn for ourselves and to find out what this mysterious box contained. When we returned to Paris, we got copies of the books which were available at the time on ancient jade and visited the collections at the Musée Guimet and the Musée Cernuschi to start to train our eyes and try to understand what we had. A kind curator at the museum was also a great help. We soon came to learn that the pieces ranged from the Han dynasty to the 18th century, with a couple of Central American jades thrown in. The adventure became increasingly exciting. And, of course, we were happy to tell Mr. Fiorillo that we were keeping the jades.

We had started on a new lifetime adventure in Asian art

“We continued search for jade carvings from that day on. Over the next 25 years we amassed a considerable collection of archaic jade, choosing as we always did one piece at a time, without relation to others that we had, based solely on our reaction to that particular piece”.

“Was it beautiful? Was the design interesting? Was the workmanship extraordinary? Did it excite us? Did it have an inner force? And, most importantly, if Myrna and I were together, did we both feel the same way about it and want to live with it?

“In 1997 we thought we should consult with an expert in the field to go over our collection and point out the things we had chosen well and exclude the mistakes we might have made – and, of course, help us avoid them in the future”.

“We decided to ask Giuseppe Eskenazi, the most important Asian art dealer in the world, whom we had met over the years. We were both in New York for Asia Week.

“It was there that we asked if he could suggest someone to whom we could turn. Without hesitation he said, In that difficult field, there is only one scholar I would rely on, who happens to be here this evening, Professor Filippo Salviati. Shortly thereafter, he introduced us and we were able to make an appointment for him to come to Paris to examine the collection”.

Filippo Salviati came to Paris

“The collection by then numbered approximately 600 pieces. It took about a week to go over all of them. At the end of that time, he turned to us and said, Do you realize that you have a comprehensive collection, showing the development of archaic jade from the 4th millennium bc to the Ming dynasty? Our reply was No! We had always made individual choices and didn’t realize that, in doing so, we had put together such a collection”.

“Those sessions with Filippo Salviati gave rise to exhibitions and books in the years 2000 and 2002: Radiant Stones – Archaic Chinese Jades from the Neolithic Period through the Han Dynasty and The Language of Adornment – Jade, Crystal, Amber and Glass from the Neolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty”.

“Since then our interest turned to the changes which took place in jade carving in the Zhou dynasty and reached their full development in the Han dynasty.”

“Since then our interest turned to the changes which took place in jade carving in the Zhou dynasty and reached their full development in the Han dynasty.”

“Through most of the first four millennia, jade carvers cut plaques in the shapes they wanted and often carved designs on the two faces. The principal images were of dragons, phoenixes and various patterns. Over time, the dragons and phoenixes carved on the plaques rose to the surface and then started to move through the material, going in one side and coming out the other.

IMAGE: Blade. Western Zhou dynasty,

20.9 × 6.7 cm

“While not universal, that was generally the way jade was carved for thousands of years. But in the Han dynasty the carvers progressed from making two-dimensional carvings to making three-dimensional carvings. “This was a time of strong belief in the afterlife, when the carvings of mythical animals, bixie were thought to protect the deceased in the afterlife. IMAGE: Bixie, jade. Han dynasty, 9.9 × 17.7 cm

“While not universal, that was generally the way jade was carved for thousands of years. But in the Han dynasty the carvers progressed from making two-dimensional carvings to making three-dimensional carvings. “This was a time of strong belief in the afterlife, when the carvings of mythical animals, bixie were thought to protect the deceased in the afterlife. IMAGE: Bixie, jade. Han dynasty, 9.9 × 17.7 cm

“These complex, supernatural, winged animals, which could fly through the sky, were protective spirits. When looked at carefully, we can still see the power they express, which springs from the intense beliefs of the carvers of that period”.

“In the Han dynasty, the Chinese reached the epitome of refinement, of originality and artisanship”.

“With the advent of Buddhism, when beliefs shifted from concentration on the afterlife and were replaced by belief in reincarnation, where the body was no longer something to be preserved, but just a shell for the spirit, the jade artisans lost the capacity to imbue their carvings with that force which had been fed over the past centuries by a fundamental belief in what they were creating”.

“Later pieces may still be beautiful, but they no longer have the same power to move you. After completing the work on Two Americans in Paris, which I must say was an overwhelming undertaking, and once more the concept of Jean-Paul Desroches who had the idea of an exhibition which would present all the things that Myrna and I collected over 50 years, I assured myself that I would never undertake a second one, especially at my age. But when Jean-Paul described the idea of an exhibition based on the “Beginning of the World – According to the Chinese,” and told me of the text from the 1st millennium bc about creation, and showed me the parallels with the explanations in the Bible and in other cultures and, furthermore, pointed out the fact that I held objects which would illustrate that story and bring it to life, I could not resist”.

“I very much hope that the viewer of this exhibition will share the experience I have had in participating in its creation. My only regret is that my wife Myrna is no longer here to share this pleasure with me”.

STATEMENTS BY MUSEUM DIRECTORS

Sam and Myrna Myers at the Baur Foundation

A Return to the Source

by Laure Schwartz-Arenales

“This exhibition in our museum in Geneva presents the jewels of Sam and Myrna Myers’ magnificent collection of archaic Chinese jades which, in a way, complete the Baur Collection. From time to time, there are places and objects through which, in their differences as well as in their affinities, the Baurs’ and Myers’ collections echo and complement each other”.

“This exhibition in our museum in Geneva presents the jewels of Sam and Myrna Myers’ magnificent collection of archaic Chinese jades which, in a way, complete the Baur Collection. From time to time, there are places and objects through which, in their differences as well as in their affinities, the Baurs’ and Myers’ collections echo and complement each other”.

“A great lover of Far Eastern objects, and in particular of Chinese ceramics for which the Baur Foundation is world-renowned, Swiss entrepreneur Alfred Baur moved to Geneva after his return from Sri Lanka in 1906″

Alfred and Eugénie Baur, Sri Lanka

“There, from 1920 until his death in 1951, he steadily acquired more than a hundred jades of remarkable workmanship, several of which were produced in the imperial workshops. He was particularly fond of those. Like others of his generation, he was unaware of the status and symbolic power attached to them, but thanks to wise advice from dealers, such as Gustave Loup and Tomita Kumasaku in particular, he could take justifiable pride in having assembled an impressive collection, representative of the technical and decorative sophistication of the Chinese lapidaries of the last imperial dynasty”.

“Whether they are antique in inspiration, luxuriant, purely decorative, in Mogul style, or infused with the literati aesthetic, these precious gems, carved between the 18th and 20th centuries in nephrite or jadeite, represent the very last links in a thousand year old craft tradition whose sources are dazzlingly evident in Sam and Myrna’s objects”.

“Before the pieces from the Baur collection entered the museum they delighted visitors to the Baurs’ magnificent house in Tournay where, bathed in light, they were displayed in the dining room. People are similarly captivated when, under the shrewd and perceptive gaze of Sam Myers, they discover his magnificent jades, glistening in the sunlight that shines in from the exquisite garden at La Celle-Saint-Cloud”.

“Pierres radieuses (Radiant Stones), the title of the first catalogue devoted to Sam and Myrna’s collection, written twenty years ago by Filippo Salviati, is an apt description of the jades chosen, thanks to the inspired taste of these collectors. They are as thrilling in the shimmering light of day as when they were first carved, and come to life when they are worn close to the body as pendants set against silk”.

“It is touching to discover that Myrna Myers and Eugénie Baur shared a passion for Chinese textiles and hardstone ornaments, which they converted into fashionable modern jewelry. Eugénie Baur wore many of them, which are now in the museum’s collection, and can be seen in photographs showing her dressed in the style of the Twenties, wearing these delicate exotic jewels from China. For Myrna, as we know, it all began with a little cicada amulet. Mounted on a silk cord by Joel Arthur Rosenthal (before he opened on Place Vendôme as JAR), this Han-era pendant that she so often wore was in the first collection of jades that Sam discovered in Philadelphia in the early 1970s”.

“Reminiscing about the circumstances of this purchase, Sam makes much of the attraction he immediately felt for these objects; their significance eluded him at the time but, like Alfred Baur, he intuitively understood their inner radiance and beauty”.

“Like all beginnings, whether or not they are just a matter of chance, that point of departure in Ascona remains the foundation of the Myers collection. You can hardly imagine a more suitable place than this former fishing village, still teeming with creativity and the free-spirited idealism that had made it famous. James Joyce, Erich Mühsam, Rudolf Laban, Carl Jung, Max Weber, Isadora Duncan, Paul Klee, Henry Van de Velde, Walter Gropius, Hans Arp, Thomas Mann – these were just some of the many reform-minded individuals, theosophers, dancers, artists and scientists seeking refuge from the industrial culture dominating Northern Europe and drawn to the harmony of the place, who spent time in Ascona.

“At the turn of the twentieth century, a number of them moved to Monte Verità, a little wooded hill that in 1926 became the property of Swiss-German banker Eduard von der Heydt, whose collection of non-Western art is now the nucleus of the Rietberg Museum in Zurich. From the 1930s on, many would meet in the lakeside conference room of the intellectual discussion group Eranos, a meeting place between East and West. Historian of religions, Mircea Eliade, went so far as to describe Monte Verità as a sort of axis mundi, between Heaven and Earth”.

“The owner of Casa Serodine, Wladimir Rosenbaum, Sam and Myrna’s first mentor, also belonged to these circles. This charismatic scholar was a brilliant jurist in Zurich, at the time mixing with the artistic and literary avant-garde, as was his wife, Aline Valangin, who was Carl Jung’s assistant. It is as if the intellectual fervor of Ascona had breathed life into Sam and Myrna’s cabinet of curiosities and their Parisian gallery, where foremost specialists in Asian art were regularly invited to study their treasures. It followed naturally that these prestigious jades should find their way to Geneva, to a museum which, thanks to Alfred and Eugénie Baur, is the only one in Switzerland exclusively dedicated to oriental art”.

“Warm thanks are extended to Jean-Paul Desroches, enabler, coordinator and indefatigable architect of this splendid project, as well as to the Museum’s Board of Trustees for their support in making it happen.

“We also had the pleasure of collaborating with the Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques de Nice and its director Adrien Bossard, which was a thoroughly rewarding and stimulating experience. Finally, I am profoundly grateful to those wonderful collectors, Sam Myers, who has been ready with such tactful and generous advice at every step of the way, and Myrna, whose presence can be felt on every page of the exhibition book.

Fondation Baur. 8 rue Munier-Romilly, 1206 Geneva – Switzerland. Phone: +41 22 704 32 82. https://www.fondation-baur.ch/en

Myrna Myers and the Genesis

of the Musée des Arts Asiatiques de Nice

by Adrien Bossard

“The Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques de Nice is a relatively recent initiative of the Conseil Départemental des Alpes-Maritimes. It was the brainchild of Marie-Pierre Foissy-Aufrère, working in close collaboration with the national museums as well as with dealers and collectors”.

“The Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques de Nice is a relatively recent initiative of the Conseil Départemental des Alpes-Maritimes. It was the brainchild of Marie-Pierre Foissy-Aufrère, working in close collaboration with the national museums as well as with dealers and collectors”.

“The challenge for the museum’s first curator in the mid-1990s was to draw on the Pritzker Prize winner Kenzo Tange’s architectural principles in a nearly completed building and assemble a collection of Asian art which would make the whole thing resonate. More than a century after the establishment of such prestigious collections as those of Emile Guimet, Henri Cernuschi and Alfred Baur, the museum did not have the benefit of a vast and visionary collection of that sort. The context had considerably changed, and originality and singularity became the determining factors”.

“The works to be exhibited in the museum were therefore chosen above all for their qualities as fascinating and evocative masterpieces. Twenty years after its inauguration, attendance at the museum has exceeded the symbolic threshold of one million visitors. It continues to fulfill its role as a bridge between Asia and the West while respecting its original spirit and intention. But it has also adapted to contemporary social and cultural changes and has become a museum of the 21st century in its own right”.

“The exhibition The Beginning of the World – According to the Chinese, is one of the important events in the museum’s 2020-2023 cultural program. This rigorous and innovative project presents an extraordinary corpus of jades from the Myers collection”.

“The beauty and the forms of the pieces are an invitation to the public to immerse themselves in a Chinese civilization made up of concepts and ideas that are sometimes the complete antithesis of those of the West. It is a voyage of discovery that will delight beginners and connoisseurs alike”.

Remembering Myrna Myers

“The exhibition is a wonderful tribute to Myrna Myers in a museum that is greatly indebted to her”.

“Marie-Pierre Foissy-Aufrère remembers the first time she met Myrna Myers; it was through Marie Catherine Rey, her main contact at the Musée Guimet. This led to frequent meetings and many conversations. Their professional understanding soon turned into a real friendship. Madame Foissy-Aufrère cherishes the memory of a discerning, sensitive and knowledgeable person with a deep passion for Asia and a gift for sharing it”.

“Thanks to what she learned from Jean-Paul Desroches, she developed unerring taste. The pieces Myrna and Marie-Pierre would select were both precious and subtle”.

“Thanks to what she learned from Jean-Paul Desroches, she developed unerring taste. The pieces Myrna and Marie-Pierre would select were both precious and subtle”.

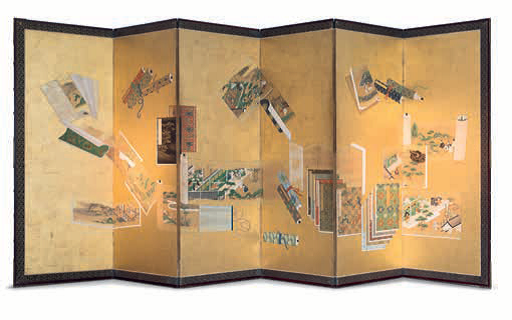

“Madame Foissy-Aufrère has two favorite anecdotes about her friend. The first concerns the time they spent together in London for Asia Week. Myrna had chosen a very British hotel. It was beautiful, warm and welcoming, and they liked it very much. The second describes the advice Myrna gave the museum in its acquisition of a pair of Japanese screens. The curator’s first choice was a screen with a motif of wisteria tumbling down onto water lilies, a precursor of Monet, strikingly aesthetic but very expensive”.

“Myrna steered her toward a wiser alternative, a pair of screens from the Tosa School, dating back to the 18th century and decorated with scrolls and books. She pointed out how rare it was for pairs to turn up in the art market and how representative the decoration was of Japanese taste”. IMAGE: Six fold Makemono-zu screen, Japan, Tosa School, 18th century, 168 × 378 cm. Nice, Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques, acc. no. 98.6.1

“The soundness of that advice is still relevant today. Three works (two textiles and an archaeological object) entered the collections of the Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques through Myrna Myers. They are exceptional pieces which the museum keeps in state-of-the-art conditions for the benef it of our visitors”.

“Dating back to the first half of the 18th century, the longpao dragon robe conjures up an image of the universe with, at its center, the five-clawed dragon, symbol of the emperor”. IMAGE: Emperor’s court robe, embroidered silk with seed pearls. Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, 145 × 190 cm

“Dating back to the Han dynasty (206 bc – 220 ad), the money tree is characteristic of Sichuan province. It is a burial piece that would have accompanied the deceased in the afterlife. The money tree has a wealth of iconography and is unique in France”.

“It is currently being analyzed in depth in order to gain a better understanding of it. The third piece dates back to the second half of the 18th century. It is a jiangyi robe which was worn by a Daoist priest during ceremonies. It is decorated with a diagram of the universe, adorned with initiatory symbols”. IMAGE: Detail of Daoist priest’s robe (detail) Qing dynasty, 138 × 204 cm. Musée des Arts asiatiques de Nice, acc. no. 2006.2.1

“I would like to extend my warmest thanks to the ever generous and enthusiastic Sam Myers, whose collection of jades will amaze, surprise and move visitors to the exhibition”.

“I would also like to express my gratitude to Jean-Paul Desroches, the indefatigable and unfailingly erudite curator of the exhibition, as well as to Laure Schwartz, the architect of the project’s success. Organizing an exhibition is always a wonderful human adventure. It is all the more wonderful when there is a strong link among the people involved”.

Nice, Musée Départemental des Arts Asiatiques. 405, Promenade des Anglais Arenas. 06200 NICE. Phone: 33(0)4.92.29.37.00. https://maa.departement06.fr/en/asian-art-museum-13422.html

CURATORS & PARTNERSHIP

General curator: Laure Schwartz-Arenales

Guest curator: Jean-Paul Desroches

Partnership: Adrien Bossard, Musée des Arts Asiatiques, Nice, France

Scenography: Nicole Gérard

CATALOGUE

The Beginning

of the World

Size: 23 x 29 cm

Pages: 296

Illustrations: 250

Cover: cardboard laminated

Bilingual work: French and English

50 €

Put up for sale on October 22, 2020

COEDITOR: Co-published with the Baur Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland

AUTHORS

Filippo Salviati: gives a solid scientific basis to this ensemble by placing the jades in their historical context.

Jean-Paul Desroches: guides us in their reading by addressing the themes of the cult of Heaven and the cult of Earth.

Laure Schwartz-Arenales: opens the great celestial bestiary with the sacred animals of the Four Directions.

Stephen Little: the way of the “Tao” which federates, condenses and regenerates all that circulates in Heaven and on Earth.

Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud:, he unveils the invaluable discoveries of celestial observers over the millennia.

Adrien Bossard: concludes by inviting us to follow in the footsteps of the sinologist and poet Victor Segalen.