SENSE OF HUMOR

July 15, 2018, through January 6, 2019

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington

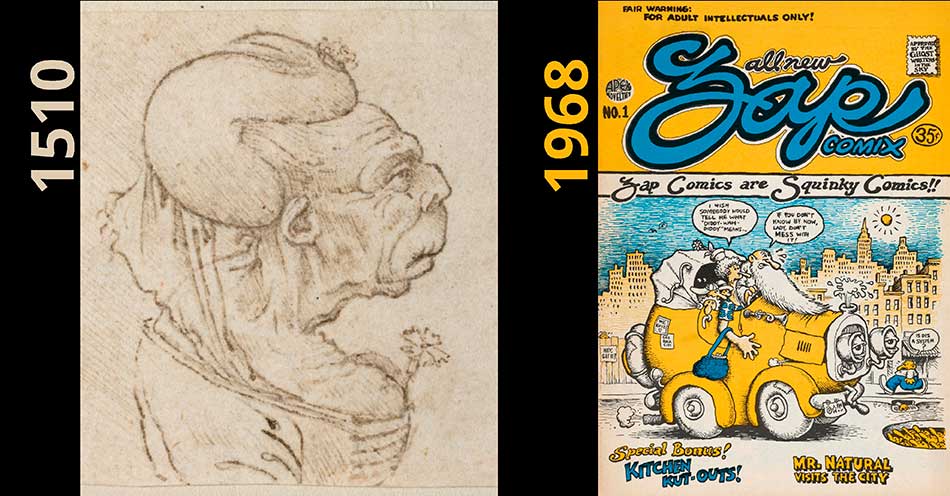

LEFT: Francesco Melzi (1491-1568/70) after Leonardo da Vinci, detail of “Two Grotesque Heads” RIGHT: Robert Crumb (artist, author), Apex Novelties (publisher) Zap #1, 1968

LEFT: Francesco Melzi (1491-1568/70) after Leonardo da Vinci, detail of “Two Grotesque Heads” RIGHT: Robert Crumb (artist, author), Apex Novelties (publisher) Zap #1, 1968

Exhibition Highlights

Prints and drawings have consistently served as popular media for humor in art. Sense of Humor

focuses on the emergence of humorous images in prints and drawings from the 15th to 20th centuries.

15th Century

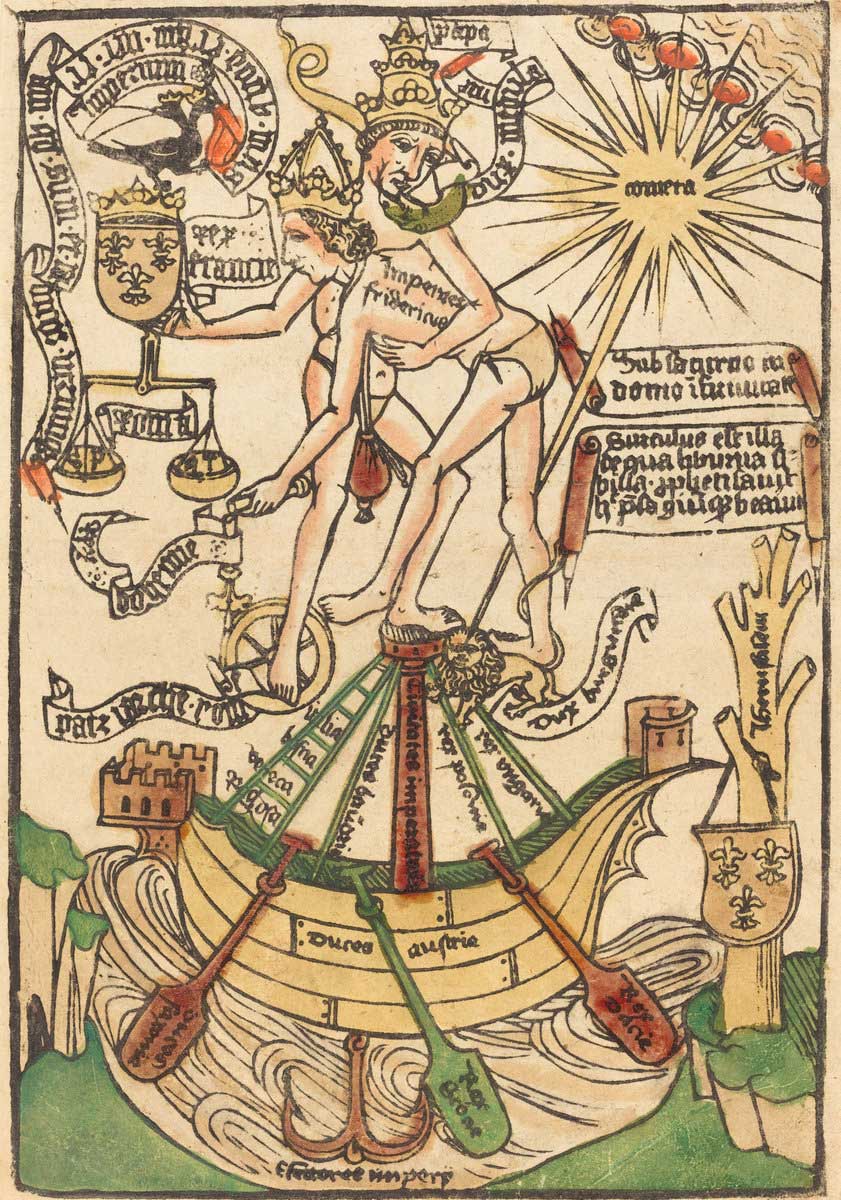

Allegory of the Meeting of Pope Paul II and Emperor Frederick III (c. 1470)

Early political cartoon showing the pope and emperor engaged in a wrestling match.

German 15th Century, Allegory of the Meeting of Pope Paul II and Emperor Frederick III, c. 1470, woodcut, hand-colored in green, red lake, yellow, tan, and orange, image: 41.3 x 29.2 cm (16 1/4 x 11 1/2 in.) sheet: 38.4 x 28.8 cm (15 1/8 x 11 5/16 in.) overall (external frame dimensions): 59.7 x 44.5 cm (23 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

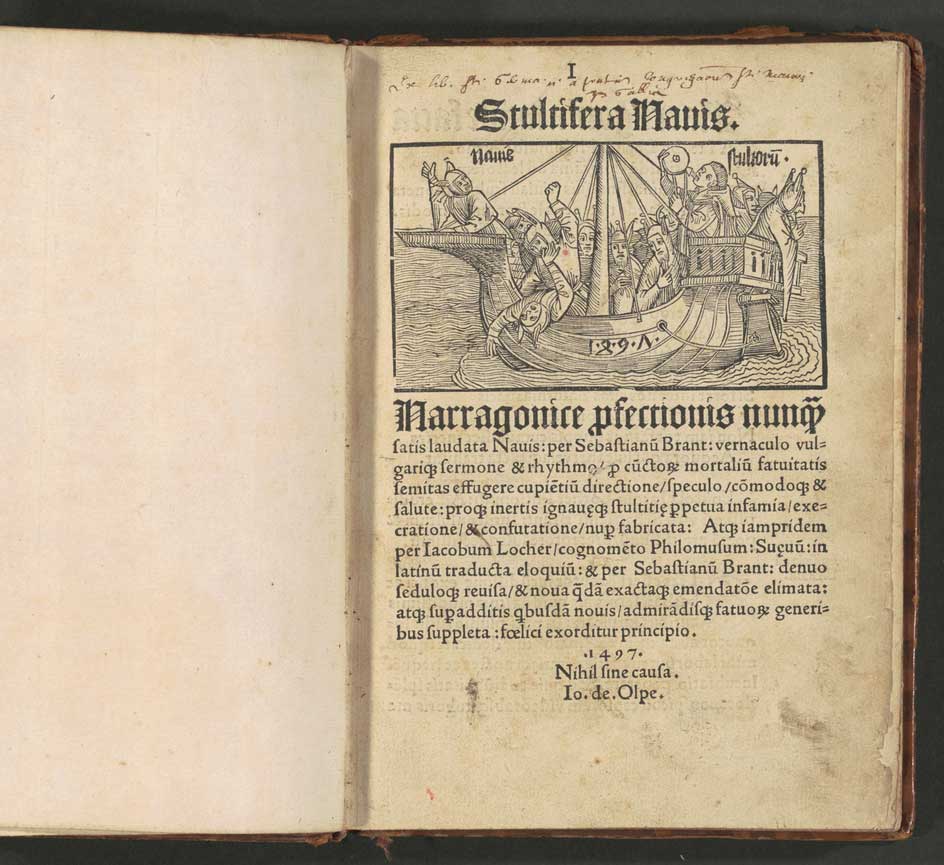

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer and Various Artists, Sebastian Brant (author)

“Stultifera navis” (Ship of Fools), 1st August, 1497

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer and Various Artists, Sebastian Brant (author) “Stultifera navis” (Ship of Fools), 1st August, 1497, bound volume with 117 woodcut illustrations from 112 blocks, book: 21.59 x 16.19 x 3.02 cm (8 1/2 x 6 3/8 x 1 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, William B. O’Neal Fund.

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer and Various Artists, Sebastian Brant (author) “Stultifera navis” (Ship of Fools), 1st August, 1497, bound volume with 117 woodcut illustrations from 112 blocks, book: 21.59 x 16.19 x 3.02 cm (8 1/2 x 6 3/8 x 1 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, William B. O’Neal Fund.

16th Century

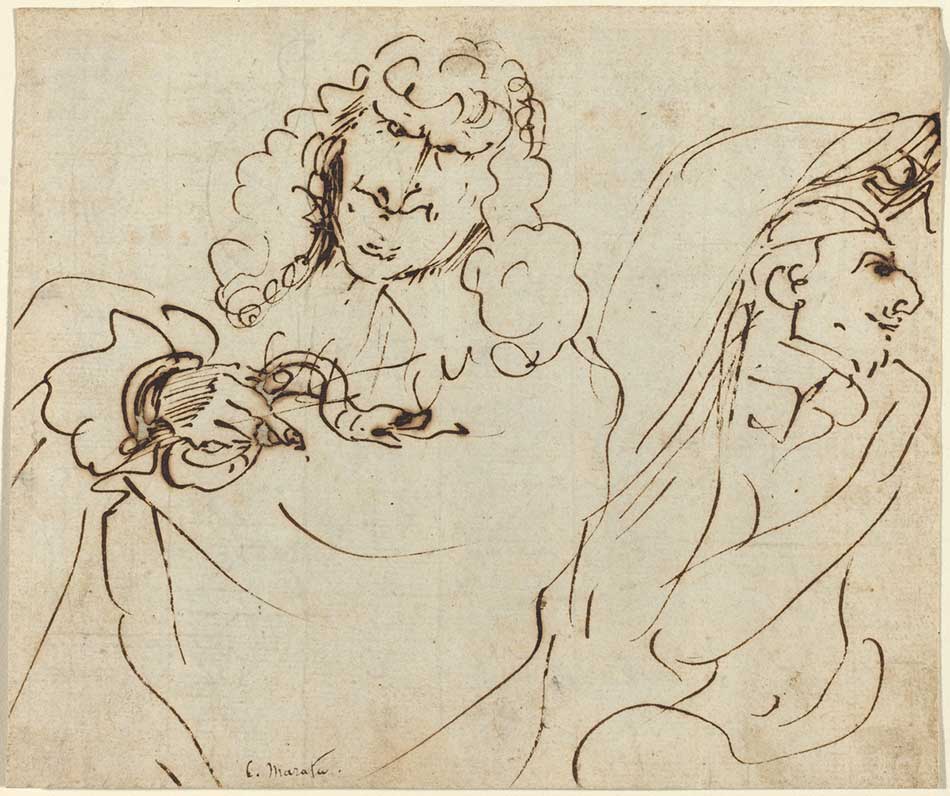

Francesco Melzi after Leonardo da Vinci: “Two Grotesque Heads” While not yet intended as caricatures of individuals, Italian works reflected the Renaissance interest in the human figure and emotion. Leonardo da Vinci explored facial features and expressions in drawings like Two Grotesque Heads (1510s). Created by his pupil, Francesco Melzi, the pen-and-ink drawing of an elderly woman and man in profile appears to be more a generic type than a study of an actual figure, but shows the exaggerated features that would come to define caricature.

Francesco Melzi after Leonardo da Vinci, “Two Grotesque Heads”, pen and brown ink, overall (approximate): 4.5 x 9.9 cm (1 3/4 x 3 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Edward Fowles.

Francesco Melzi after Leonardo da Vinci, “Two Grotesque Heads”, pen and brown ink, overall (approximate): 4.5 x 9.9 cm (1 3/4 x 3 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Edward Fowles.

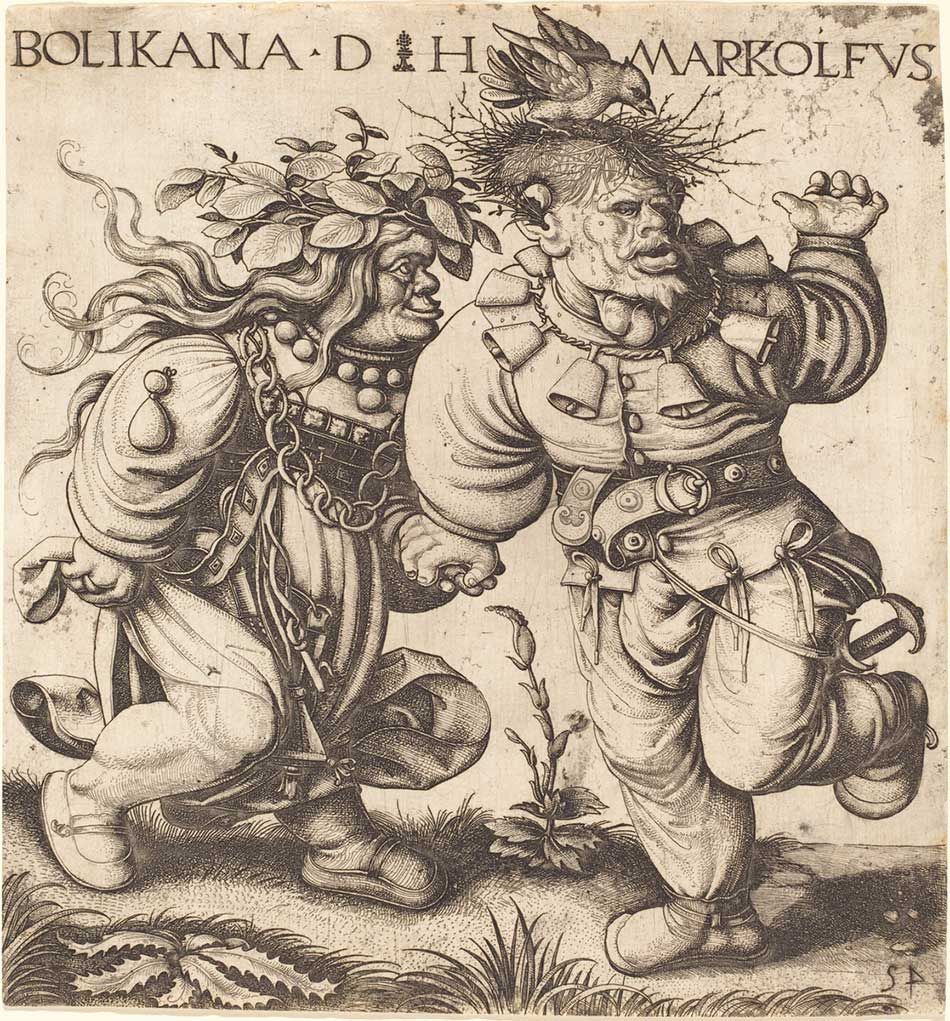

Daniel Hopfer: “Bolikana and Markolfus”

Typical examples from northern Europe include Daniel Hopfer’s Bolikana and Markolfus

(early 16th century), which derives from the popular story of a clever peasant outwitting a person

of higher status and education.

Daniel Hopfer, “Bolikana and Markolfus”, etching and engraving, sheet: 23.7 x 22.2 cm (9 5/16 x 8 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

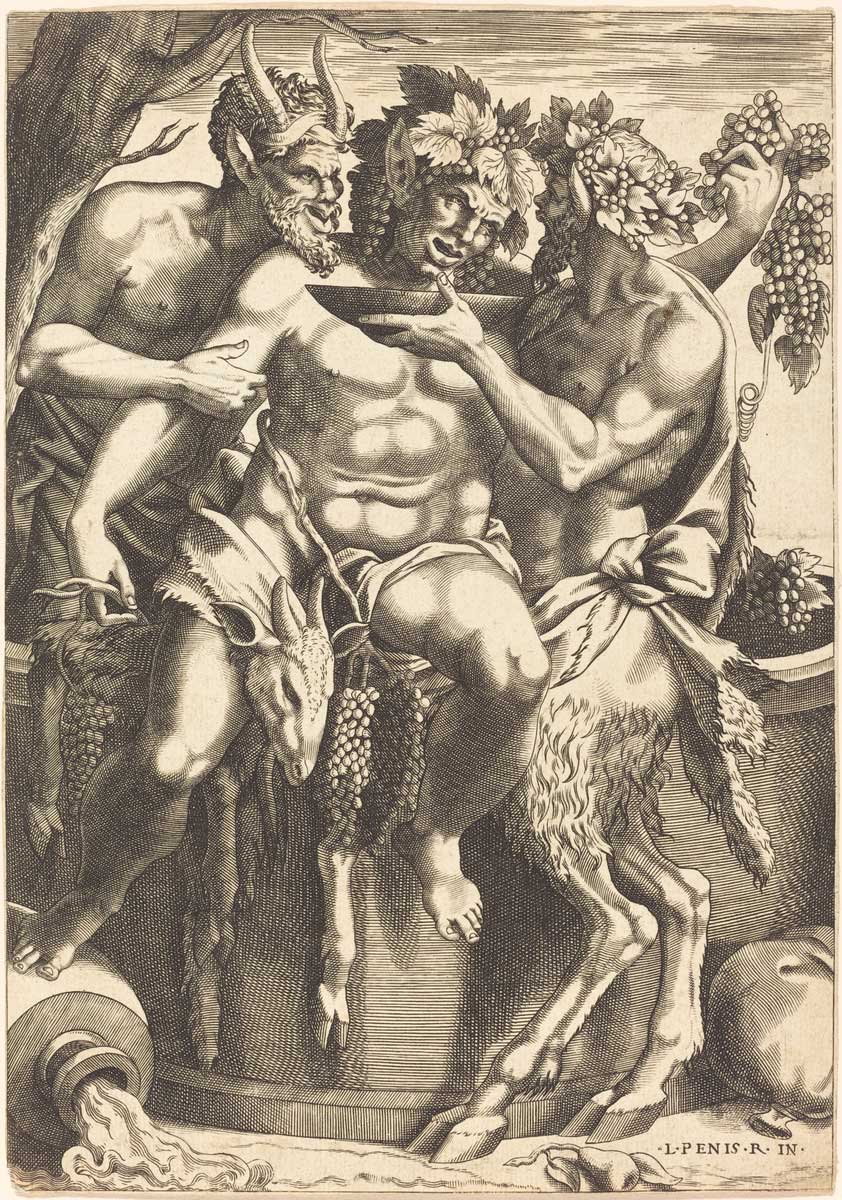

René Boyvin after Luca Penni: “Silenus”

René Boyvin after Luca Penni, “Silenus”, engraving, sheet: 23.6 x 16.6 cm (9 5/16 x 6 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

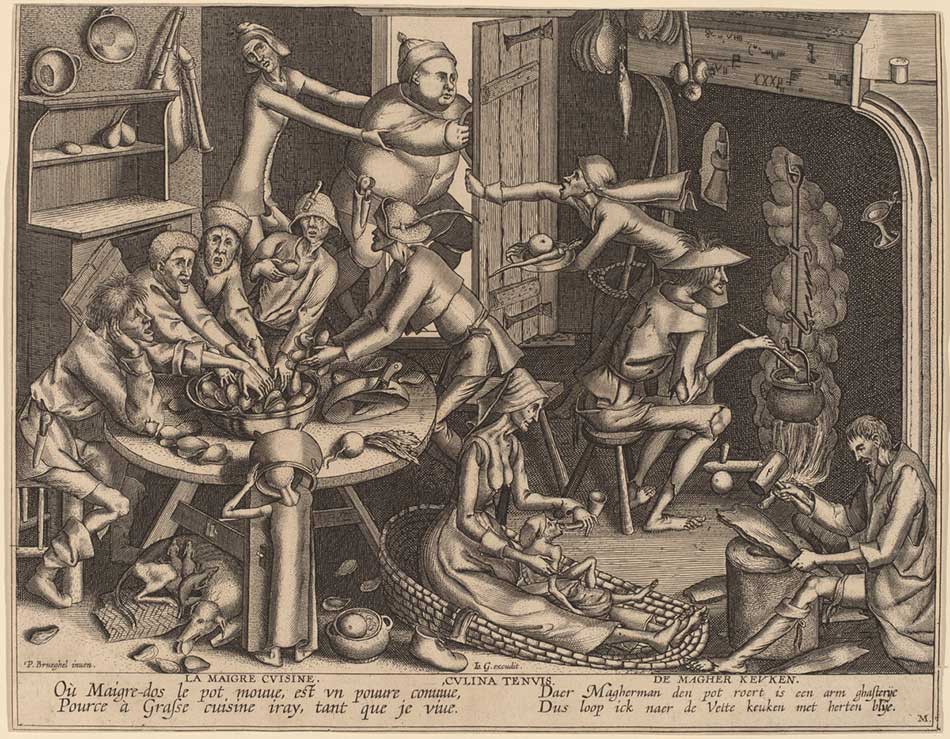

Joan Galle after Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The Thin Kitchen”, in or after 1563

Joan Galle after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Thin Kitchen”, in or after 1563 engraving sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 22.4 x 28.9 cm (8 13/16 x 11 3/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Hans Liefrinck I after Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The Fat Kitchen”, in or after 1563

Hans Liefrinck I after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Fat Kitchen”, in or after 1563, engraving, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 21.8 x 28.2 cm (8 9/16 x 11 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Hans Liefrinck I after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Fat Kitchen”, in or after 1563, engraving, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 21.8 x 28.2 cm (8 9/16 x 11 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

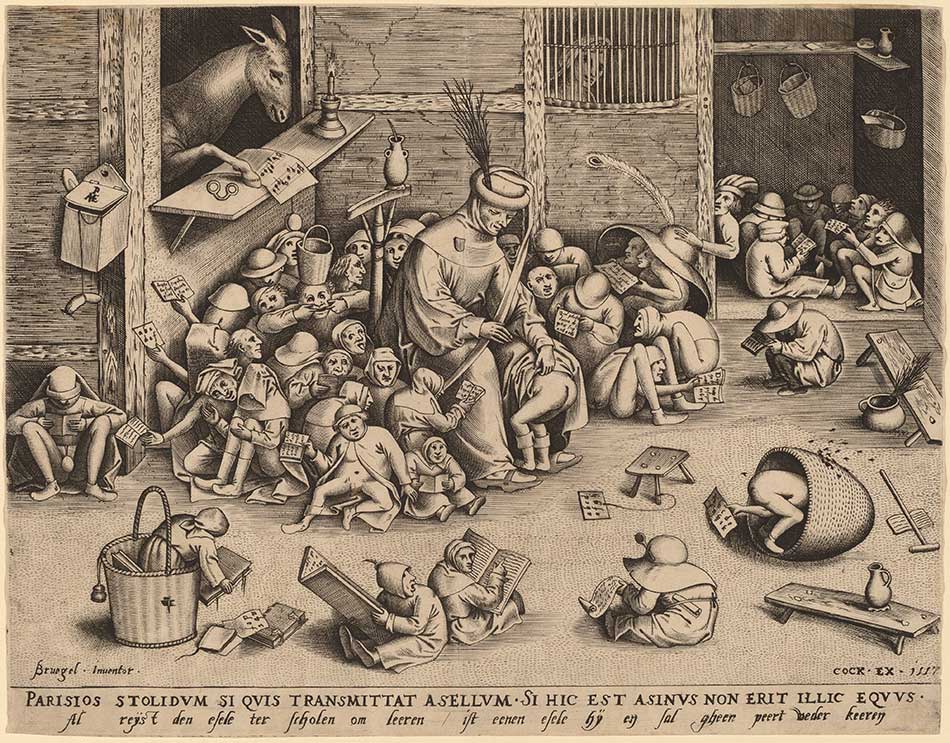

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The Ass at School”, 1557

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Ass at School”, 1557, engraving, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 23.6 x 30.4 cm (9 5/16 x 11 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Jane C. Carey as an addition to the Addie Burr Clark Memorial Collection.

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Ass at School”, 1557, engraving, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 23.6 x 30.4 cm (9 5/16 x 11 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Jane C. Carey as an addition to the Addie Burr Clark Memorial Collection.

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The Wedding of Mopsus and Nisa”, published 1570

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Wedding of Mopsus and Nisa”, published 1570, engraving, sheet: 22.2 × 29.1 cm (8 3/4 × 11 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Wedding of Mopsus and Nisa”, published 1570, engraving, sheet: 22.2 × 29.1 cm (8 3/4 × 11 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

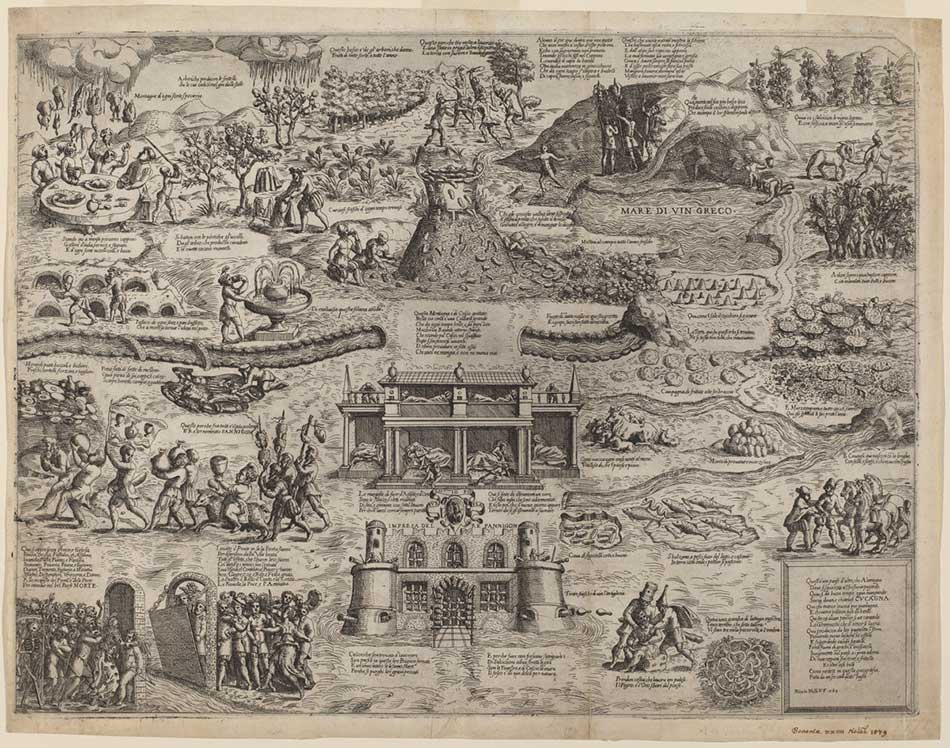

Niccolò Nelli: “The Land of Cockaigne”, 1564

Niccolò Nelli, “The Land of Cockaigne”, 1564, etching, plate: 40.7 x 53.6 cm (16 x 21 1/8 in.) sheet: 43.2 x 65.3 cm (17 x 25 11/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Niccolò Nelli, “The Land of Cockaigne”, 1564, etching, plate: 40.7 x 53.6 cm (16 x 21 1/8 in.) sheet: 43.2 x 65.3 cm (17 x 25 11/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Jusepe de Ribera: “Head of a Man”, early 1620s

Jusepe de Ribera, “Head of a Man”, early 1620s, red chalk on laid paper, image: 23.7 x 17 cm (9 5/16 x 6 11/16 in.) sheet: 30.5 x 24.5 cm (12 x 9 5/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Jusepe de Ribera, “Head of a Man”, early 1620s, red chalk on laid paper, image: 23.7 x 17 cm (9 5/16 x 6 11/16 in.) sheet: 30.5 x 24.5 cm (12 x 9 5/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

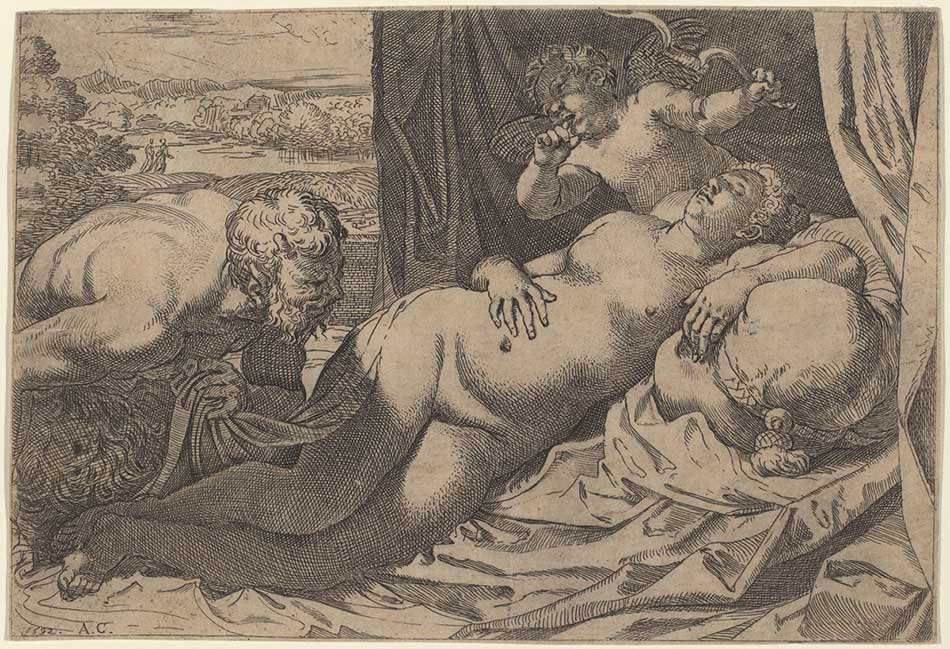

Annibale Carracci: “Venus and a Satyr”, 1592

Annibale Carracci, “Venus and a Satyr”, 1592, etching with engraving on laid paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Kate Ganz.

Annibale Carracci, “Venus and a Satyr”, 1592, etching with engraving on laid paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Kate Ganz.

17th Century

Jacques Callot, the brilliant 17th-century French observer of courtly life and costume, include a vibrant pen-and-ink drawing. Satirical images referring to specific people, events, or behaviors became common toward the end of this period.

Jacques Callot: “Two Zanni”, c. 1616

Jacques Callot, “Two Zanni”, c. 1616, etching, plate: 9.5 x 14.2 cm (3 3/4 x 5 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

Jacques Callot, “Two Zanni”, c. 1616, etching, plate: 9.5 x 14.2 cm (3 3/4 x 5 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

Jacques Callot: “Gobbi and Other Bizarre Figures”, 1616/1617

Jacques Callot, “Gobbi and Other Bizarre Figures”, 1616/1617, pen and iron gall ink with a partial sketch in graphite at upper left on laid paper, overall: 12 x 14.1 cm (4 3/4 x 5 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Jacques Callot, “Gobbi and Other Bizarre Figures”, 1616/1617, pen and iron gall ink with a partial sketch in graphite at upper left on laid paper, overall: 12 x 14.1 cm (4 3/4 x 5 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Jacques Callot: “Man Preparing to Draw his Sword”, c. 1622

Jacques Callot, “Man Preparing to Draw his Sword”, c. 1622, etching and engraving, plate: 6.2 x 8.8 cm (2 7/16 x 3 7/16 in.) sheet: 9 x 10.4 cm (3 9/16 x 4 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

Jacques Callot, “Man Preparing to Draw his Sword”, c. 1622, etching and engraving, plate: 6.2 x 8.8 cm (2 7/16 x 3 7/16 in.) sheet: 9 x 10.4 cm (3 9/16 x 4 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

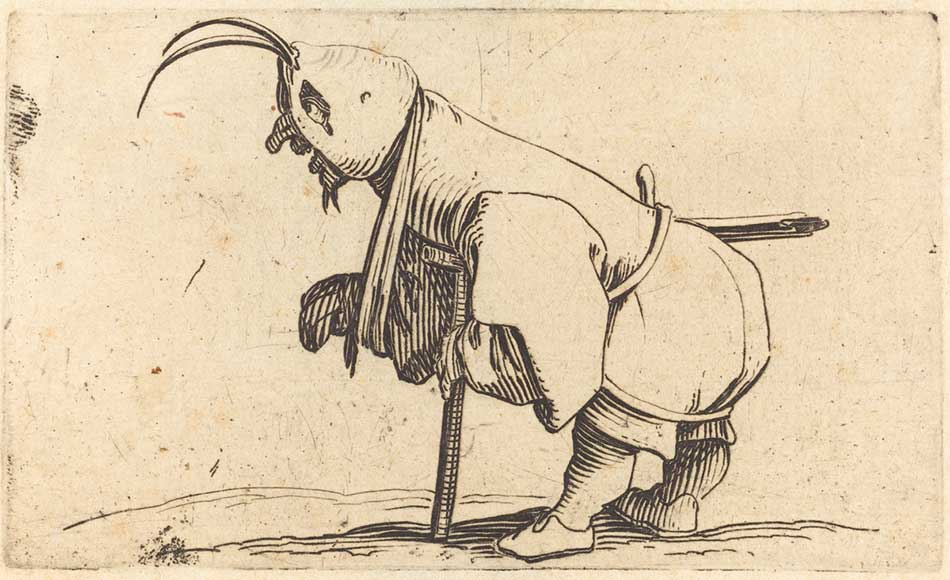

Jacques Callot: “The Hooded Cripple”, c. 1622

Jacques Callot, “The Hooded Cripple”, c. 1622, etching and engraving, plate: 5.2 x 8.6 cm (2 1/16 x 3 3/8 in.) sheet: 9.6 x 10.5 cm (3 3/4 x 4 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

Jacques Callot, “The Hooded Cripple”, c. 1622, etching and engraving, plate: 5.2 x 8.6 cm (2 1/16 x 3 3/8 in.) sheet: 9.6 x 10.5 cm (3 3/4 x 4 1/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, R.L. Baumfeld Collection.

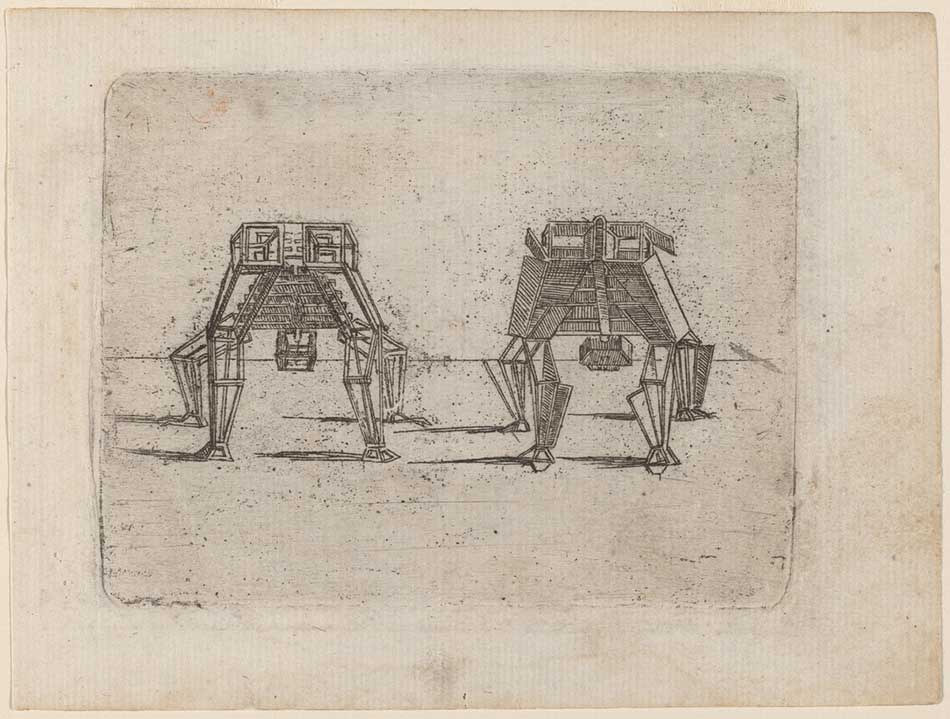

Giovanni Battista Bracelli: “Two Cubic Figures with Their Hands on the Ground”, 1624

Giovanni Battista Bracelli, “Two Cubic Figures with Their Hands on the Ground”, 1624, etching, plate: 8.5 x 11.2 cm (3 3/8 x 4 7/16 in.) sheet: 11.3 x 15 cm (4 7/16 x 5 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Giovanni Battista Bracelli, “Two Cubic Figures with Their Hands on the Ground”, 1624, etching, plate: 8.5 x 11.2 cm (3 3/8 x 4 7/16 in.) sheet: 11.3 x 15 cm (4 7/16 x 5 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Jusepe de Ribera: “The Drunken Silenus”, 1628

Jusepe de Ribera, “The Drunken Silenus”, 1628, etching on laid paper, sheet (cut within platemark): 27.2 x 35.3 cm (10 11/16 x 13 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund.

Jusepe de Ribera, “The Drunken Silenus”, 1628, etching on laid paper, sheet (cut within platemark): 27.2 x 35.3 cm (10 11/16 x 13 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund.

Rembrandt van Rijn: “Self-Portrait in a Cap, Laughing”, 1630

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Self-Portrait in a Cap: Laughing”, 1630, etching, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 5.3 x 4.4 cm (2 1/16 x 1 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Self-Portrait in a Cap: Laughing”, 1630, etching, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 5.3 x 4.4 cm (2 1/16 x 1 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Pier Francesco Mola: “Caricature with Mola Protecting Himself from a Man Holding a Viper”

Pier Francesco Mola, “Caricature with Mola Protecting Himself from a Man Holding a Viper”, pen and brown ink on laid paper, overall: 14.7 x 17.8 cm (5 13/16 x 7 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Michael Miller and Lucy Vivante.

Pier Francesco Mola, “Caricature with Mola Protecting Himself from a Man Holding a Viper”, pen and brown ink on laid paper, overall: 14.7 x 17.8 cm (5 13/16 x 7 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Michael Miller and Lucy Vivante.

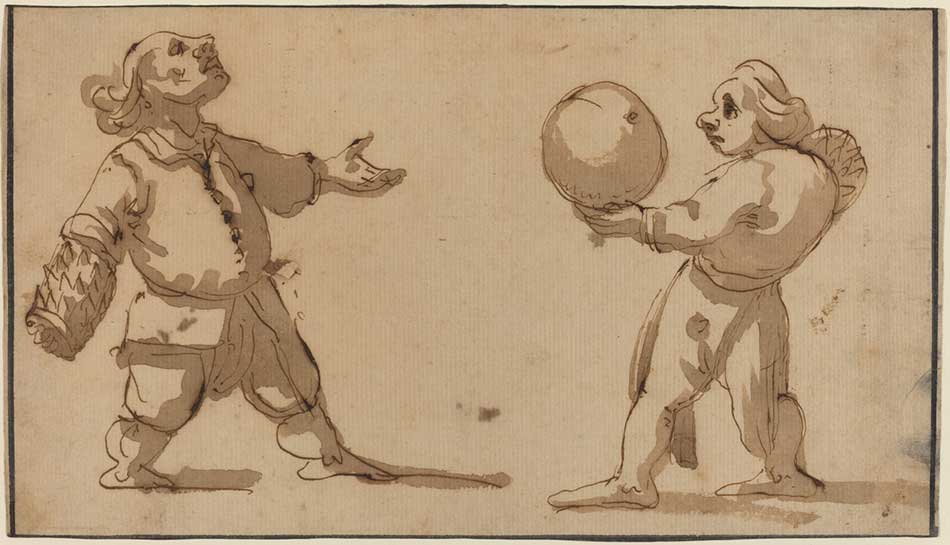

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli: “A Caricature with Ball Players”

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, “A Caricature with Ball Players”, iron gall ink on laid paper, with black ink borders, overall: 16.4 x 29 cm (6 7/16 x 11 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Benjamin and Lillian Hertzberg.

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, “A Caricature with Ball Players”, iron gall ink on laid paper, with black ink borders, overall: 16.4 x 29 cm (6 7/16 x 11 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Benjamin and Lillian Hertzberg.

Coryn Boel after David Teniers the Younger: “The Monkeys’ Barber Shop”

Coryn Boel after David Teniers the Younger, “The Monkeys’ Barber Shop”, engraving on laid paper, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 24.7 x 32 cm (9 3/4 x 12 5/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth B. Benedict.

Coryn Boel after David Teniers the Younger, “The Monkeys’ Barber Shop”, engraving on laid paper, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 24.7 x 32 cm (9 3/4 x 12 5/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth B. Benedict.

Romeyn de Hooghe: “No Monarchy, No Popery”, c. 1690

Romeyn de Hooghe, “No Monarchy, No Popery”, c. 1690, etching on laid paper, plate: 48 x 57.1 cm (18 7/8 x 22 1/2 in.) sheet: 49.5 x 59.9 cm (19 1/2 x 23 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Romeyn de Hooghe, “No Monarchy, No Popery”, c. 1690, etching on laid paper, plate: 48 x 57.1 cm (18 7/8 x 22 1/2 in.) sheet: 49.5 x 59.9 cm (19 1/2 x 23 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Cornelis Dusart: “Cereris Bacchique Amicus” (A Friend of Ceres and Bacchus)

Cornelis Dusart, “Cereris Bacchique Amicus” (A Friend of Ceres and Bacchus), mezzotint on laid paper, plate: 26.5 x 19.4 cm (10 7/16 x 7 5/8 in.) sheet: 28.1 x 21 cm (11 1/16 x 8 1/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Cornelis Dusart, “Cereris Bacchique Amicus” (A Friend of Ceres and Bacchus), mezzotint on laid paper, plate: 26.5 x 19.4 cm (10 7/16 x 7 5/8 in.) sheet: 28.1 x 21 cm (11 1/16 x 8 1/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Cornelis Dusart: “The Merry Shoemaker”, 1695

Cornelis Dusart, “The Merry Shoemaker”, 1695, etching, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 25.2 x 18 cm (9 15/16 x 7 1/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth B. Benedict.

Cornelis Dusart, “The Merry Shoemaker”, 1695, etching, sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 25.2 x 18 cm (9 15/16 x 7 1/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth B. Benedict.

18th Century

Certain artists dedicated themselves exclusively to comical subjects. A group of etchings by William Hogarth includes Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn(1738), contrasting the actresses’ roles as Roman goddesses with the earthly and humble preparations behind the curtain as they practice lines, mend stockings, and imbibe.

Pier Leone Ghezzi: “Signore Sebastiano Conca, Pittore Napoletano”

(Signore Sebastiano Conca, Neapolitan Painter), 1734/1755

Pier Leone Ghezzi, “Signore Sebastiano Conca, Pittore Napoletano (Signore Sebastiano Conca, Neapolitan Painter), 1734/1755, pen and brown ink over black chalk on laid paper mounted on album page, sheet: 31.6 x 21.5 cm (12 7/16 x 8 7/16 in.) support: 48 x 38 cm (18 7/8 x 14 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Pier Leone Ghezzi, “Signore Sebastiano Conca, Pittore Napoletano (Signore Sebastiano Conca, Neapolitan Painter), 1734/1755, pen and brown ink over black chalk on laid paper mounted on album page, sheet: 31.6 x 21.5 cm (12 7/16 x 8 7/16 in.) support: 48 x 38 cm (18 7/8 x 14 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

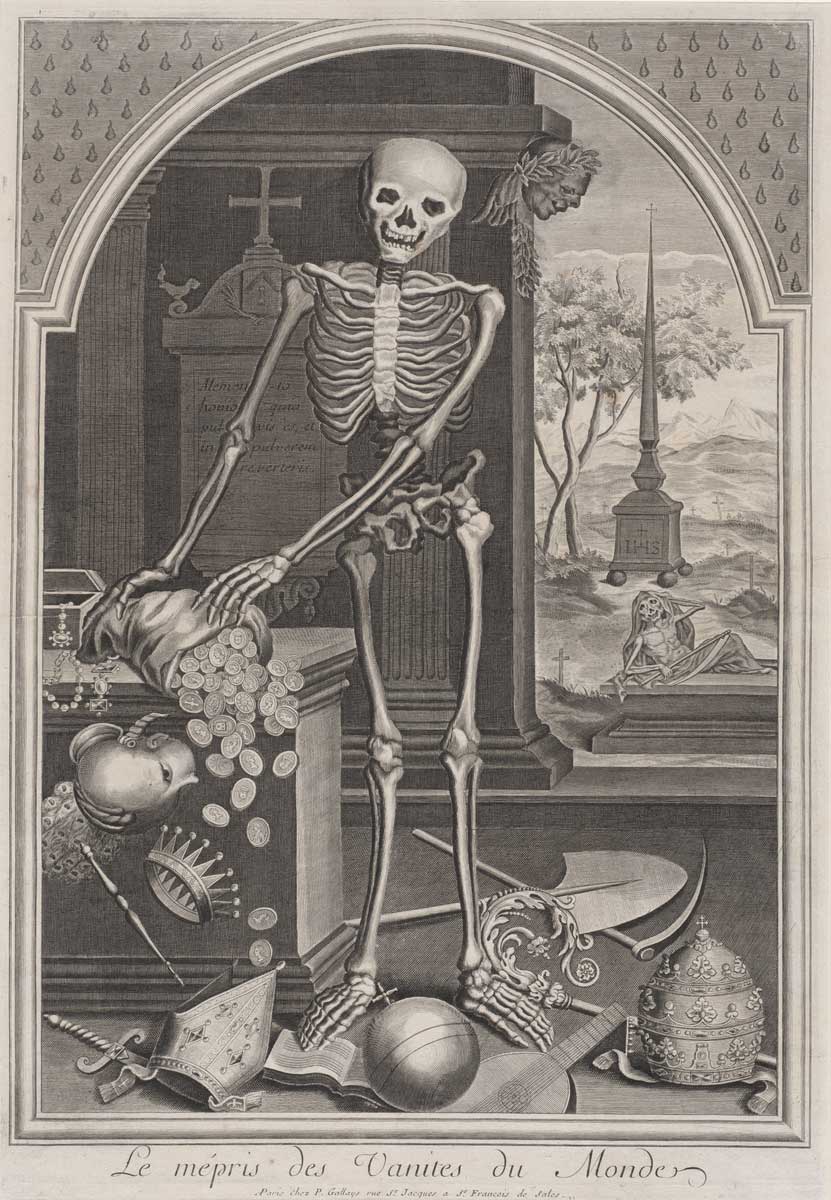

French 18th Century: “Death with Worldly Vanities”, 1700/1720

French 18th Century, “Death with Worldly Vanities”, 1700/1720, engraving on laid paper, image: 66.99 x 47.63 cm (26 3/8 x 18 3/4 in.) sheet: 75.25 x 55.25 cm (29 5/8 x 21 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

French 18th Century, “Death with Worldly Vanities”, 1700/1720, engraving on laid paper, image: 66.99 x 47.63 cm (26 3/8 x 18 3/4 in.) sheet: 75.25 x 55.25 cm (29 5/8 x 21 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Johann Jacob Schübler: “Mezzetin and Harlequin Use the Picture Frame to Catch Pantaloon and Pierrot”, c. 1729

Johann Jacob Schübler, “Mezzetin and Harlequin Use the Picture Frame to Catch Pantaloon and Pierrot”, c. 1729, pen and black ink and gray wash on laid paper; scored for transfer, overall: 13.5 x 18.6 cm (5 5/16 x 7 5/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Johann Jacob Schübler, “Mezzetin and Harlequin Use the Picture Frame to Catch Pantaloon and Pierrot”, c. 1729, pen and black ink and gray wash on laid paper; scored for transfer, overall: 13.5 x 18.6 cm (5 5/16 x 7 5/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

William Hogarth: “Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn”, 1738

William Hogarth, “Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn”, 1738, etching and engraving, sheet: 46.7 x 62.8 cm (18 3/8 x 24 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

William Hogarth, “Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn”, 1738, etching and engraving, sheet: 46.7 x 62.8 cm (18 3/8 x 24 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

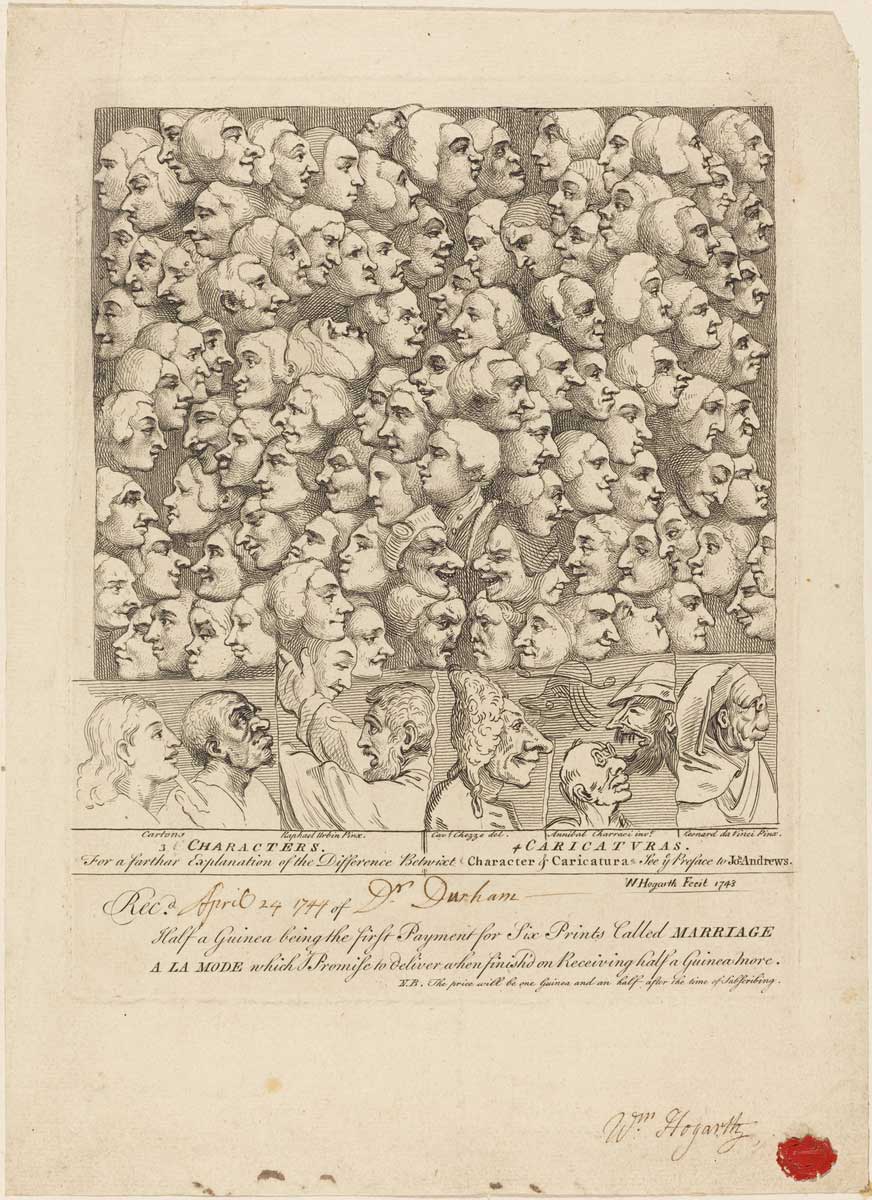

William Hogarth: “Characters and Caricaturas”, 1743

William Hogarth, “Characters and Caricaturas”, 1743, etching, plate: 26.1 x 20.5 cm (10 1/4 x 8 1/16 in.) sheet: 33.6 x 24.3 cm (13 1/4 x 9 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

William Hogarth, “Characters and Caricaturas”, 1743, etching, plate: 26.1 x 20.5 cm (10 1/4 x 8 1/16 in.) sheet: 33.6 x 24.3 cm (13 1/4 x 9 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Nicolas Delaunay after Pierre-Antoine Baudouin: Le Carquois épuisé (The Empty Quiver), 1775

Nicolas Delaunay after Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, “Le Carquois épuisé” (The Empty Quiver), 1775, etching and engraving plate: 35.7 x 25.5 cm (14 1/16 x 10 1/16 in.) sheet: 45.6 x 34.2 cm (17 15/16 x 13 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection.

Nicolas Delaunay after Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, “Le Carquois épuisé” (The Empty Quiver), 1775, etching and engraving plate: 35.7 x 25.5 cm (14 1/16 x 10 1/16 in.) sheet: 45.6 x 34.2 cm (17 15/16 x 13 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection.

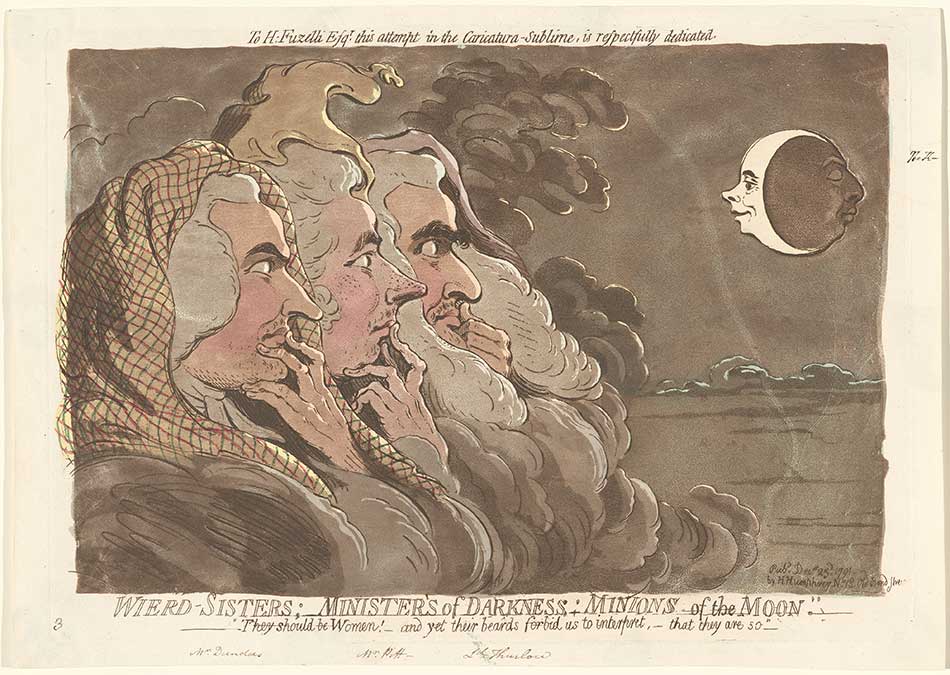

While Hogarth considered himself more a comic painter than caricaturist, later British artists like James Gillray embraced caricature. Gillray’s Wierd-Sisters; Ministers of Darkness; Minions of the Moon (1791) parodies Henry Fuseli’s painting Weird Sisters (1783), replacing the three witches from Macbeth with three ministers gazing at a moon with the faces of King George III and Queen Charlotte on it, concerned that the king has been declared unfit to rule after his bout of madness.

James Gillray: “Wierd-Sisters; Ministers of Darkness; Minions of the Moon”, 1791

James Gillray, “Wierd-Sisters; Ministers of Darkness; Minions of the Moon”, 1791, etching, engraving and aquatint printed in sepia on wove paper, with publisher’s hand-coloring and inscriptions by Gillray, plate: 24.9 x 35.1 cm (9 13/16 x 13 13/16 in.) sheet: 26.9 x 37.9 cm (10 9/16 x 14 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Anonymous Gift.

James Gillray, “Wierd-Sisters; Ministers of Darkness; Minions of the Moon”, 1791, etching, engraving and aquatint printed in sepia on wove paper, with publisher’s hand-coloring and inscriptions by Gillray, plate: 24.9 x 35.1 cm (9 13/16 x 13 13/16 in.) sheet: 26.9 x 37.9 cm (10 9/16 x 14 15/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Anonymous Gift.

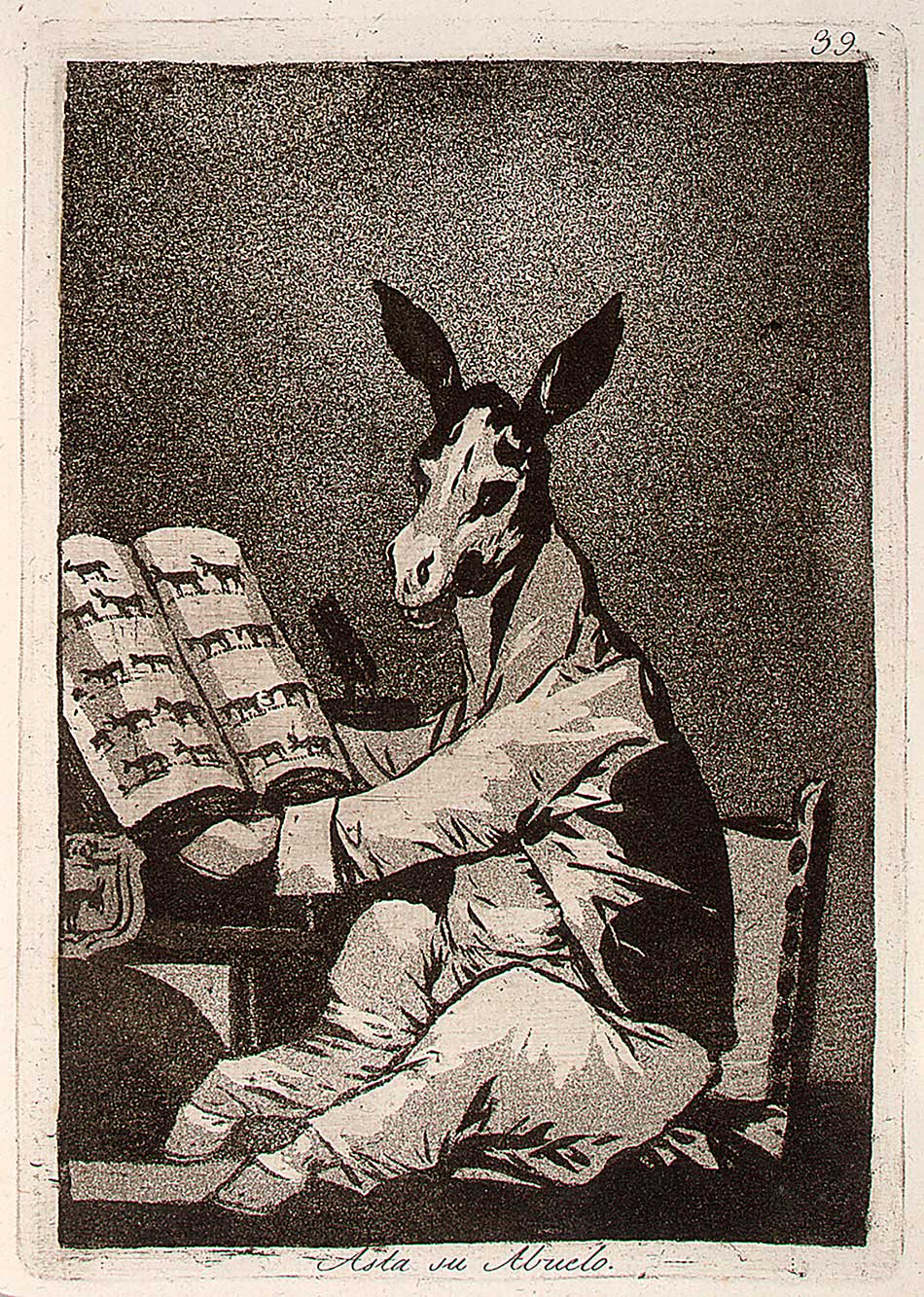

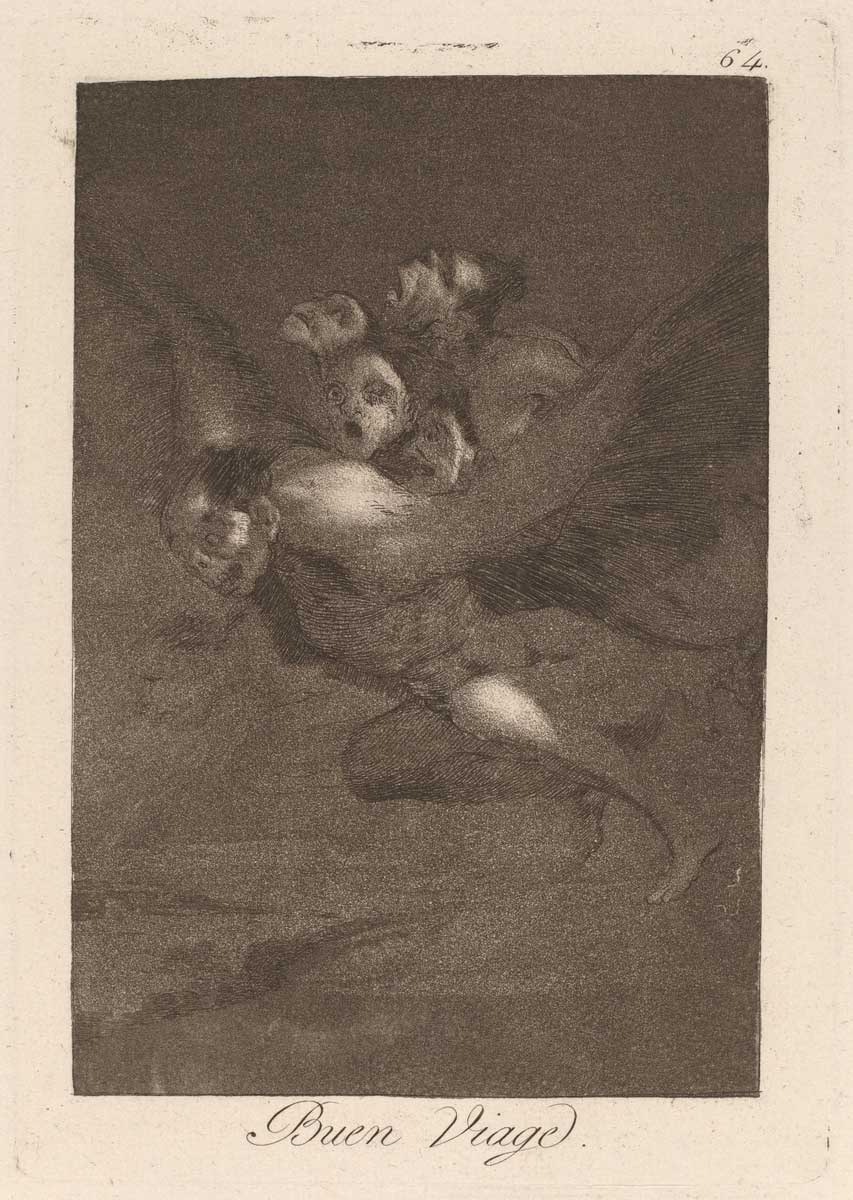

Francisco de Goya, inspired in part by the English satirists, turned a scornful eye to the vices of humanity in his Los Caprichos (1799).

Francisco de Goya: “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799

Francisco de Goya, “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799, 1 vol: 80 etchings, aquatints, drypoints, and burins. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya, “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799, 1 vol: 80 etchings, aquatints, drypoints, and burins. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya: “Ya van desplumados” (There They Go Plucked), 1797/1798

![Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746 - 1828 ), Ya van desplumados (There They Go Plucked), 1797/1798, etching, burnished aquatint and drypoint [working proof, before letters], Rosenwald Collection 1953.6.70](https://patrons.org.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/27_-Francisco-de-Goya_Ya-van-desplumados-_There-They-Go-Plucked_-17971798.jpg) Francisco de Goya, “Ya van desplumados” (There They Go Plucked), 1797/1798, etching, burnished aquatint and drypoint [working proof, before letters] plate: 21.6 x 15.2 cm (8 1/2 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.3 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya, “Ya van desplumados” (There They Go Plucked), 1797/1798, etching, burnished aquatint and drypoint [working proof, before letters] plate: 21.6 x 15.2 cm (8 1/2 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.3 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya: “Al Conde Palatino” (To the Count Palatine), in or before 1799

![Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746 - 1828 ), Al Conde Palatino (To the Count Palatine), in or before 1799, etching, aquatint, drypoint and burin [working proof], Rosenwald Collection 1953.6.71](https://patrons.org.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/28_-Francisco-de-Goya_Al-Conde-Palatino-_To-the-Count-Palatine_in-or-before-1799.jpg) Francisco de Goya, “Al Conde Palatino” (To the Count Palatine), in or before 1799, etching, aquatint, drypoint and burin [working proof] plate: 21.7 x 15.3 cm (8 9/16 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.3 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya, “Al Conde Palatino” (To the Count Palatine), in or before 1799, etching, aquatint, drypoint and burin [working proof] plate: 21.7 x 15.3 cm (8 9/16 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.3 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya: “La filiacion” (The Filiation), in or before 1799

![Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746 - 1828 ), La filiacion (The Filiation), in or before 1799, etching and aquatint [working proof], Rosenwald Collection 1953.6.72](https://patrons.org.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/29_Francisco-de-Goya_La-filiacion-The-Filiation-in-or-before-1799.jpg) Francisco de Goya, “La filiacion” (The Filiation), in or before 1799, etching and aquatint [working proof] plate: 21.6 x 15.2 cm (8 1/2 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.4 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya, “La filiacion” (The Filiation), in or before 1799, etching and aquatint [working proof] plate: 21.6 x 15.2 cm (8 1/2 x 6 in.) sheet: 26.4 x 20 cm (10 3/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya: “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799

Francisco de Goya, “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799, 1 vol: 80 etchings, aquatints, drypoints, and burins. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Francisco de Goya, “Los caprichos” (first edition), published 1799, 1 vol: 80 etchings, aquatints, drypoints, and burins. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

19th Century

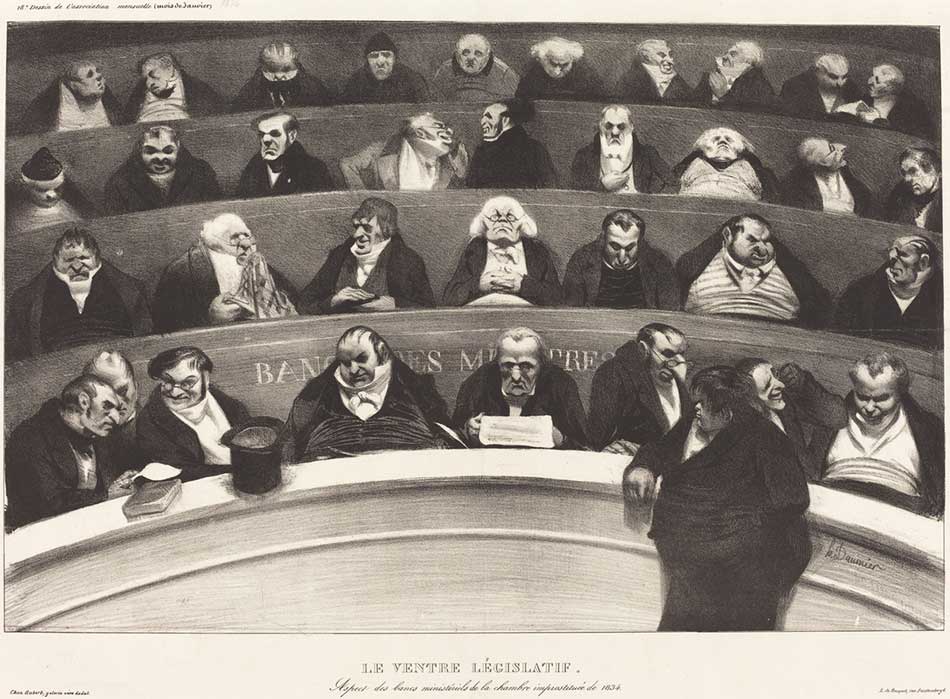

The development of lithography in the 19th century allowed for a new level of dissemination because prints could be reproduced quickly and affordably. Artists such as Honoré Daumier took advantage of these developments to create fierce political satires and caricatures that landed him in jail. Included in the exhibition is Daumier’s Le Ventre Législatif (The Legislative Belly) (1834), a famous image that mocks the conservative members of France’s Chamber of Deputies. While the identity of each politician would have been known at the time, the print continues to resonate today as a satire of politicians, generally. Satire reached the height of its influence during the 19th century and was censured as a result. In response to the threat of severe punishment and even jail, artists adapted by creating more nuanced and universal criticism of current events.

French 19th Century: “Provinciaux visitant les curiosités de Paris”

(Provincials Visiting the Curiosities of Paris), c. 1805

French 19th Century, “Provinciaux visitant les curiosités de Paris” (Provincials Visiting the Curiosities of Paris), c. 1805, etching with publisher’s hand coloring in watercolor on pale green laid paper, plate: 22 x 27.2 cm (8 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.) sheet: 25.7 x 34.3 cm (10 1/8 x 13 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Katharine Shepard Fund.

French 19th Century, “Provinciaux visitant les curiosités de Paris” (Provincials Visiting the Curiosities of Paris), c. 1805, etching with publisher’s hand coloring in watercolor on pale green laid paper, plate: 22 x 27.2 cm (8 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.) sheet: 25.7 x 34.3 cm (10 1/8 x 13 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Katharine Shepard Fund.

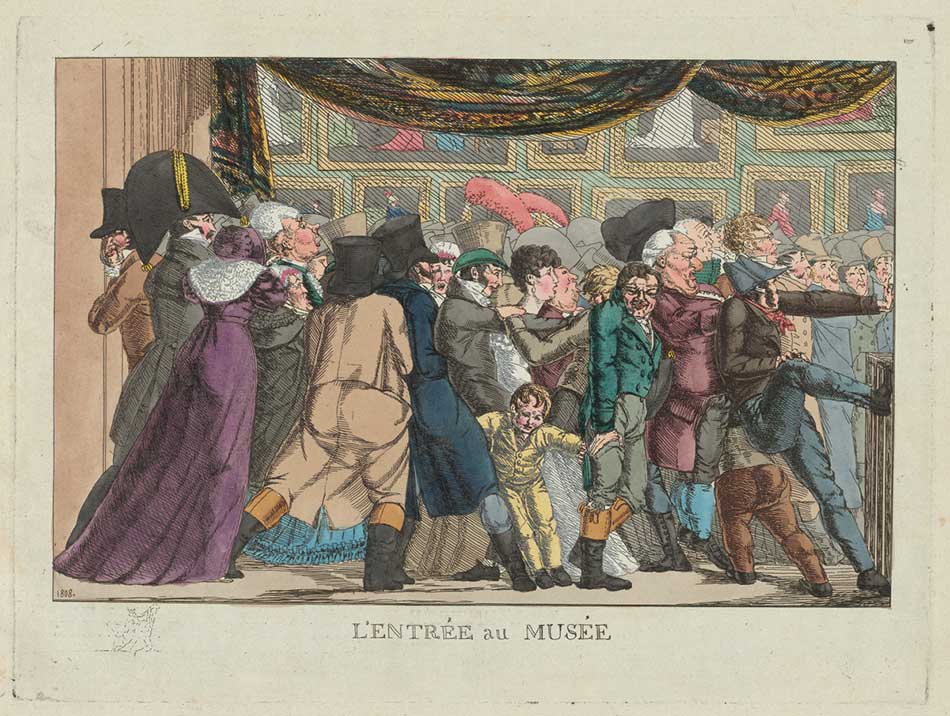

French 19th Century: “L’entrée au musée” (Entrance to the Museum), 1808

French 19th Century, “L’entrée au musée”(Entrance to the Museum), 1808, etching with publisher’s hand coloring in watercolor on pale green laid paper, plate: 20 x 26.7 cm (7 7/8 x 10 1/2 in.) sheet: 25.6 x 32.7 cm (10 1/16 x 12 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Katharine Shepard Fund.

French 19th Century, “L’entrée au musée”(Entrance to the Museum), 1808, etching with publisher’s hand coloring in watercolor on pale green laid paper, plate: 20 x 26.7 cm (7 7/8 x 10 1/2 in.) sheet: 25.6 x 32.7 cm (10 1/16 x 12 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Katharine Shepard Fund.

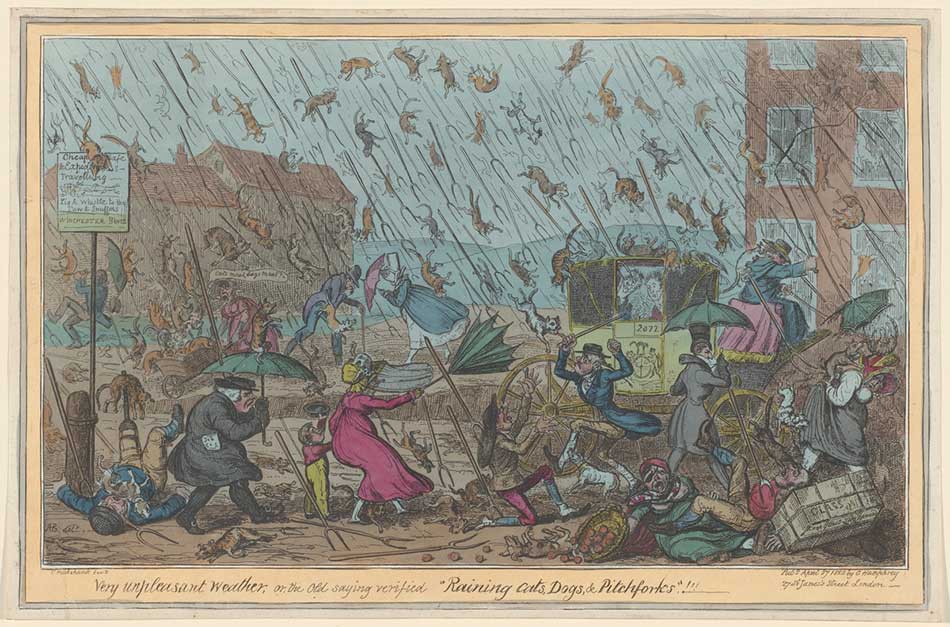

George Cruikshank: “Very unpleasant weather”, 1820

George Cruikshank, “Very unpleasant weather”, 1820, etching and engraving with publisher’s hand coloring image: 22.1 x 36.2 cm (8 11/16 x 14 1/4 in.) sheet: 25.6 x 39.4 cm (10 1/16 x 15 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

George Cruikshank, “Very unpleasant weather”, 1820, etching and engraving with publisher’s hand coloring image: 22.1 x 36.2 cm (8 11/16 x 14 1/4 in.) sheet: 25.6 x 39.4 cm (10 1/16 x 15 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

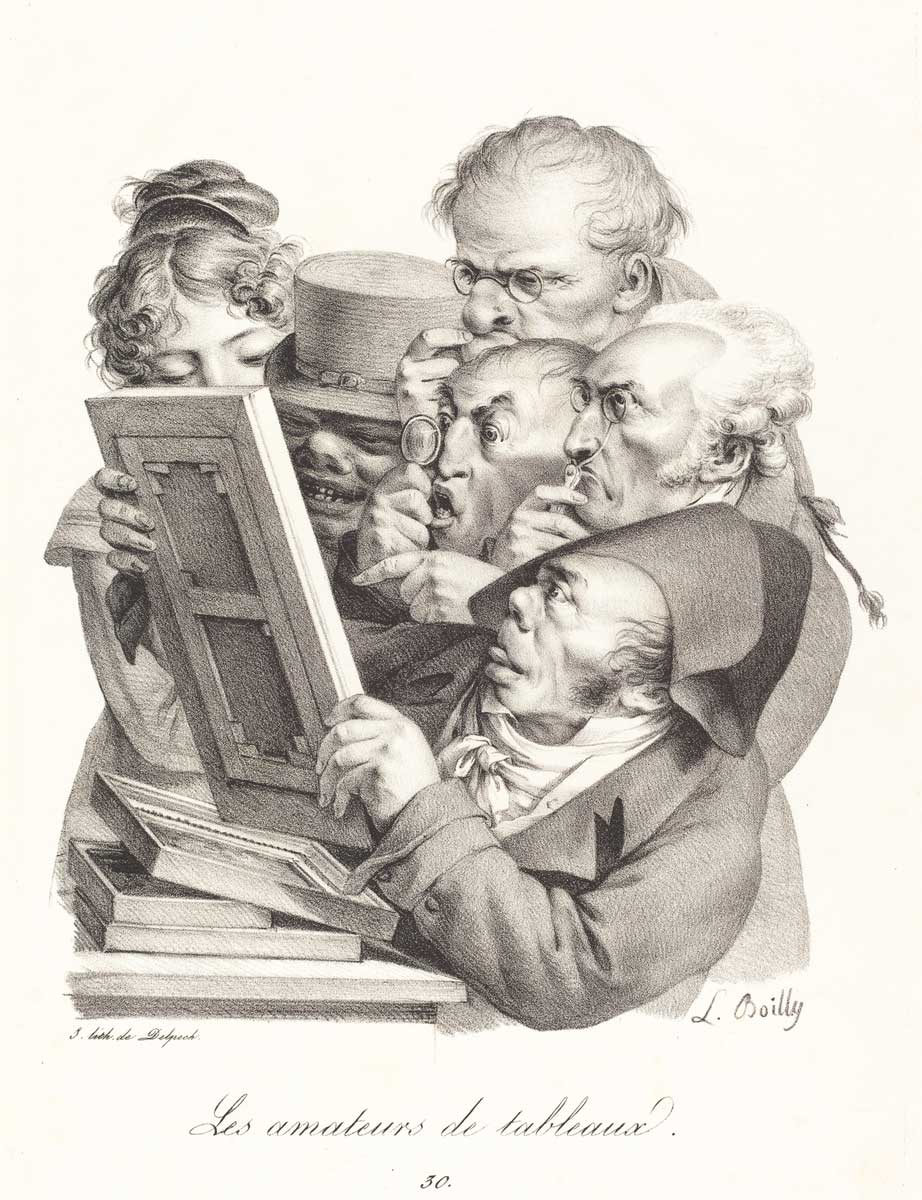

Louis-Léopold Boilly: “Les amateurs de tableaux” (The Picture Enthusiasts), 1823

Louis-Léopold Boilly, “Les amateurs de tableaux” (The Picture Enthusiasts), 1823, crayon lithograph in black on wove paper, sheet: 35.5 x 25.5 cm (14 x 10 1/16 in.)National Gallery of Art, Washington Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Louis-Léopold Boilly, “Les amateurs de tableaux” (The Picture Enthusiasts), 1823, crayon lithograph in black on wove paper, sheet: 35.5 x 25.5 cm (14 x 10 1/16 in.)National Gallery of Art, Washington Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Jean-Ignace-Isidore Grandville and Eugène-Hippolyte Forest:

“Artillerie du Diable” (The Devil’s Artillery), 1834

Jean-Ignace-Isidore Grandville and Eugène-Hippolyte Forest, “Artillerie du Diable” (The Devil’s Artillery), 1834, lithograph, overall: 26.5 x 36 cm (10 7/16 x 14 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frank Anderson Trapp.

Jean-Ignace-Isidore Grandville and Eugène-Hippolyte Forest, “Artillerie du Diable” (The Devil’s Artillery), 1834, lithograph, overall: 26.5 x 36 cm (10 7/16 x 14 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Frank Anderson Trapp.

Honoré Daumier: “Baissez le rideau, la farce est jouée” (Lower the Curtain, the Farce is Over), 1834

Honoré Daumier, “Baissez le rideau, la farce est jouée “(Lower the Curtain, the Farce is Over), 1834, lithograph, image: 19.9 x 27.7 cm (7 13/16 x 10 7/8 in.) sheet: 27.5 x 36.1 cm (10 13/16 x 14 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Honoré Daumier, “Baissez le rideau, la farce est jouée “(Lower the Curtain, the Farce is Over), 1834, lithograph, image: 19.9 x 27.7 cm (7 13/16 x 10 7/8 in.) sheet: 27.5 x 36.1 cm (10 13/16 x 14 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Honoré Daumier, “Le Ventre Législatif” (The Legislative Belly), February 5, 1834

Honoré Daumier, “Le Ventre Législatif” (The Legislative Belly), February 5, 1834, lithograph, sheet: 35.5 x 52 cm (14 x 20 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Mary E. Maxwell Fund)

Honoré Daumier, “Le Ventre Législatif” (The Legislative Belly), February 5, 1834, lithograph, sheet: 35.5 x 52 cm (14 x 20 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Mary E. Maxwell Fund)

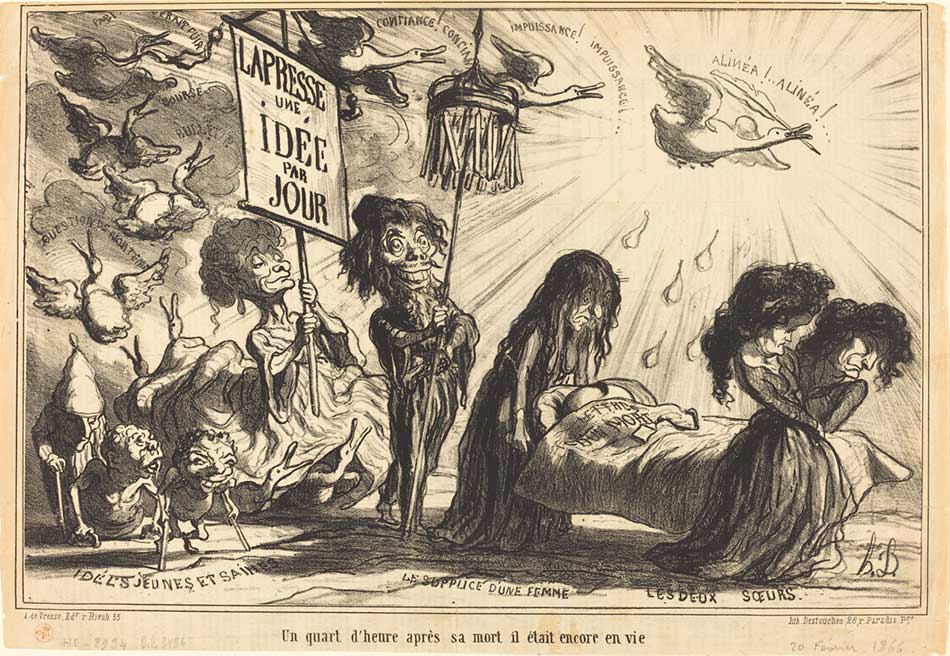

Honoré Daumier: “Un Quart d’heure après sa mort il était encore en vie”

(A Quarter of an Hour after His Death, He Was Still Alive), 1866

Honoré Daumier, “Un Quart d’heure après sa mort il était encore en vie” (A Quarter of an Hour after His Death, He Was Still Alive), 1866, lithograph on newsprint, sheet: 28.6 x 41.8 cm (11 1/4 x 16 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Honoré Daumier, “Un Quart d’heure après sa mort il était encore en vie” (A Quarter of an Hour after His Death, He Was Still Alive), 1866, lithograph on newsprint, sheet: 28.6 x 41.8 cm (11 1/4 x 16 7/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

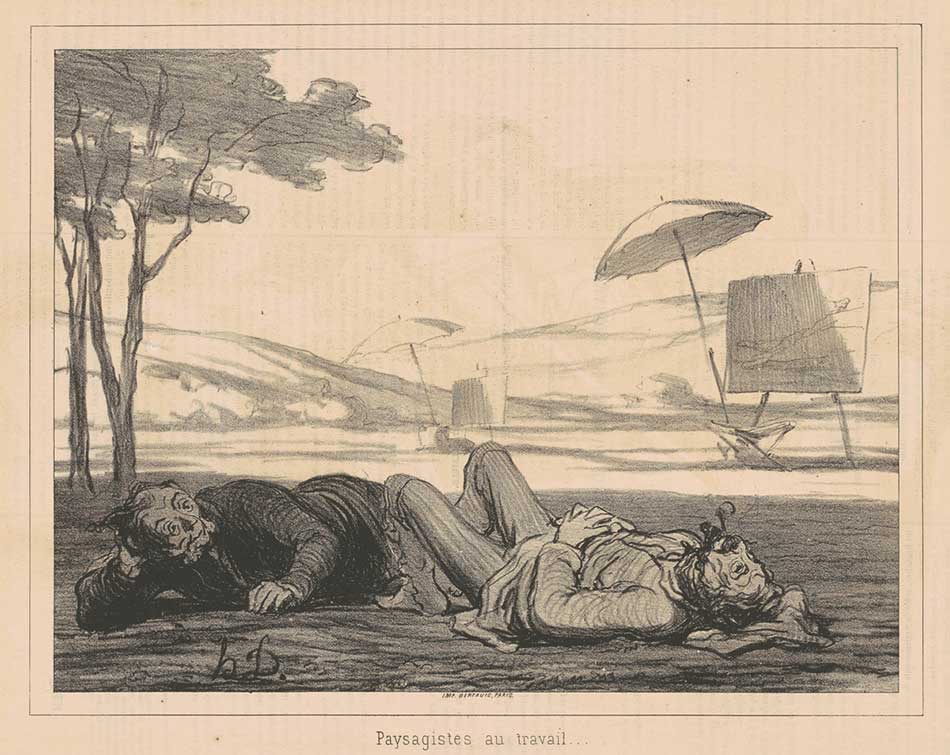

Honoré Daumier, “Paysagistes au travail” (Landscape Artists at Work), 1862

Honoré Daumier, “Paysagistes au travail” (Landscape Artists at Work), 1862, lithograph, sheet: 31.8 x 45.1 cm (12 1/2 x 17 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Honoré Daumier, “Paysagistes au travail” (Landscape Artists at Work), 1862, lithograph, sheet: 31.8 x 45.1 cm (12 1/2 x 17 3/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

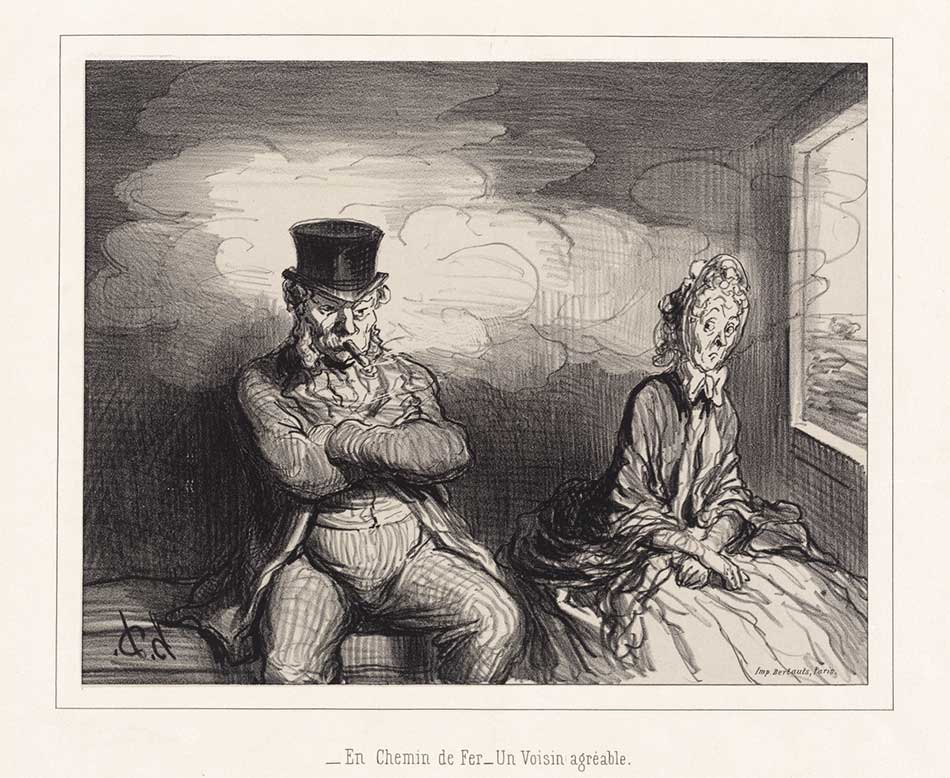

Honoré Daumier: “En Chemin de fer… un voisin agréable” (On the Railroad: A Pleasant Neighbor), 1862

Honoré Daumier, “En Chemin de fer… un voisin agréable” (On the Railroad: A Pleasant Neighbor), 1862, lithograph, sheet: 31.5 x 44.6 cm (12 3/8 x 17 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Honoré Daumier, “En Chemin de fer… un voisin agréable” (On the Railroad: A Pleasant Neighbor), 1862, lithograph, sheet: 31.5 x 44.6 cm (12 3/8 x 17 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

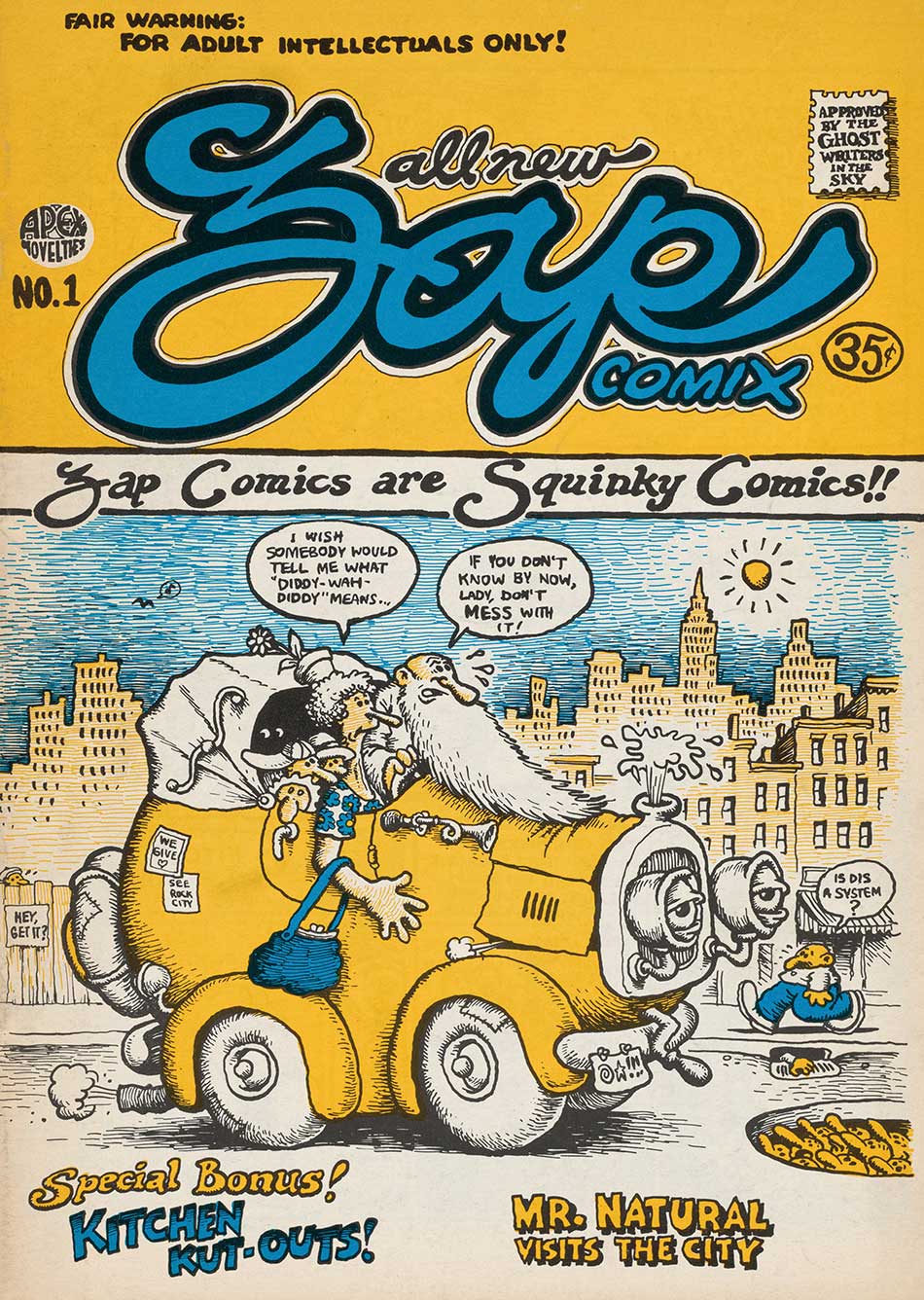

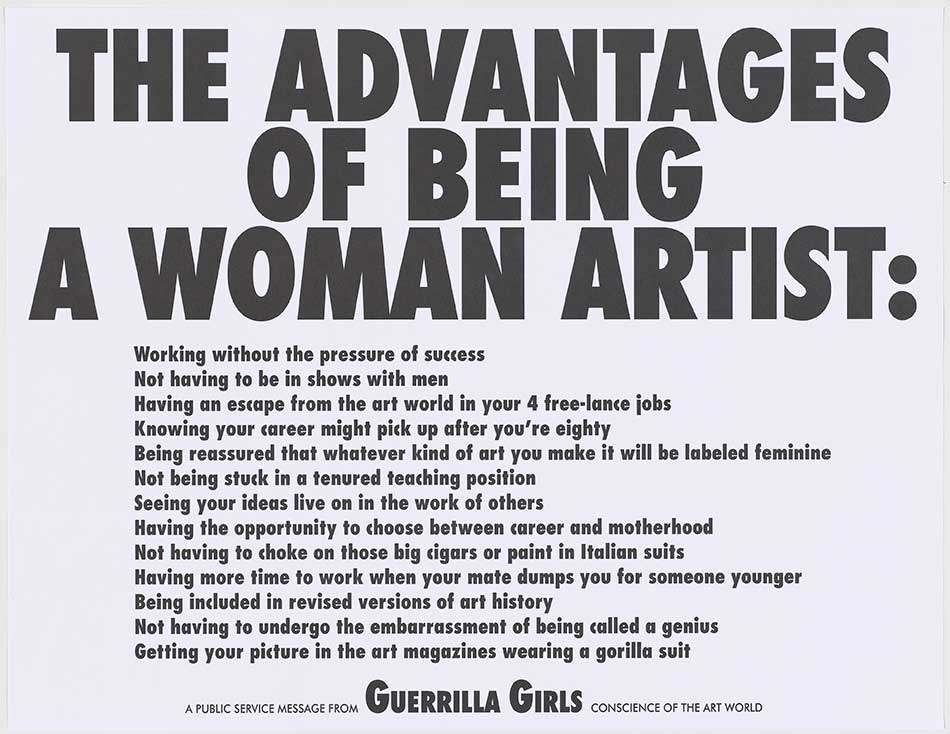

The final room of Sense of Humor focuses on the 20th century and encompasses both the gentle fun of works by George Bellows, Alexander Calder, and Mabel Dwight and the biting satire of Hans Haacke and Rupert García. Works by professional cartoonists such as R. Crumb, George Herriman, Winsor McCay, and Art Spiegelman are presented alongside mainstream artists like Calder, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. Especially in the second half of the century, artists used humor to expose biases and inequities in modern society. Posters on view by the Guerrilla Girls, the feminist art collective founded in 1985, drip with tongue-in-cheek irony to draw attention to the unequal treatment of women by the art establishment. Even revered works of art become the target of lampooning. In his Reflections on The Scream (1990), Lichtenstein satirizes Edvard Munch’s The Scream, replacing the Norwegian artist’s iconic depiction of existential suffering with a more banal type of pain: a screaming baby who appears as a black hole of discontent.

Robert Crumb (artist, author), Apex Novelties (publisher) Zap #1, 1968

Robert Crumb (artist, author), Apex Novelties (publisher) Zap #1, 1968, 28-page paperback bound volume with half-tone and offset lithograph illustrations in black and cover in full color, sheet: 24.13 x 17.15 cm (9 1/2 x 6 3/4 in.) open: 24.13 x 34.29 cm (9 1/2 x 13 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of William and Abigail Gerdts.

Robert Crumb (artist, author), Apex Novelties (publisher) Zap #1, 1968, 28-page paperback bound volume with half-tone and offset lithograph illustrations in black and cover in full color, sheet: 24.13 x 17.15 cm (9 1/2 x 6 3/4 in.) open: 24.13 x 34.29 cm (9 1/2 x 13 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of William and Abigail Gerdts.

Guerrilla Girls, “The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist”, 1988

Guerrilla Girls, “The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist”, 1988, offset lithograph in black on wove paper, overall: 43.2 x 56 cm (17 x 22 1/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Gallery Girls in support of the Guerrilla Girls.

Guerrilla Girls, “The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist”, 1988, offset lithograph in black on wove paper, overall: 43.2 x 56 cm (17 x 22 1/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Gallery Girls in support of the Guerrilla Girls.

Tribute to the donors of works of art in this exhibition

AILSA MELLON BRUCE

(1901-1969)

A great collector and benefactor of the National Gallery of Art to which she has donated important works, some of which are part of this exhibition. Ailsa and her brother Paul Mellon inherited their passion for art and collecting from their father Andrew William Mellon, founder of the National Gallery of Art. A prominent part of these donations is shown in this exhibition.

LESSING JULIUS ROSENWALD

LESSING JULIUS ROSENWALD

(1891-1979)

Lessing Julius Rosenwald was a great collector of works of art on paper, he participated in the creation of the first collections of the National Gallery of Art, making important donations, together with other great philanthropists such as Samuel Henry Kress, Josep Early Widener and Chester Dale. A prominent part of these donations is shown in this exhibition.

JOSEPH EARLY WIDENER

JOSEPH EARLY WIDENER

(1871-1943)

Joseph Early Widener Comes from a family of outstanding collectors, he participated in the creation of the first collections of the National Gallery of Art by donating important works of art, along with other great philanthropists such as Samuel Henry Kress, Lessing Julius Rosenwald and Chester Dale. Some of these works is part of this exhibition.

STATEMENT

Earl A. Powell III

director, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

“Humor is a fundamental element of the human experience, and has too often been overlooked in the history of art”. “This exhibition takes a closer look at the many ways comedic works of art—specifically works on paper—have been used to elicit a laugh, make a critique, or reveal a truth. This exhibition would truly not have been possible without the extraordinary depth and breadth of our collection of prints and drawings.”

Exhibition Organization and Curators. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington. is curated by Jonathan Bober, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings; Judith Brodie, curator and head of the department of American and modern prints and drawings; and Stacey Sell, associate curator, department of old master drawings, all National Gallery of Art, Washington.

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington

6th and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20565

Telephone: (202) 737-4215 Accessibility Information: (202) 842-6905

http://www.nga.gov/