GOLDEN KINGDOMS

Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas

February 28–May 28, 2018

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Serpent Labret with Articulated Tongue, Gold, Aztec, A.D. 1300–1521, Mexico.

Serpent Labret with Articulated Tongue, Gold, Aztec, A.D. 1300–1521, Mexico.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2015 Benefit Fund and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2016

Joanne Pillsbury

The Met’s Andrall E. Pearson Curator of the Arts of the Ancient Americas

“Ideas about artistic production in the ancient Americas have traditionally been based on works in ceramic and stone—objects of durable materials,” “But there were also exquisitely worked objects of rare and fragile materials, most of which were destroyed at the time of the Spanish Conquest. “Countless works of gold and silver were melted down, and delicate native manuscripts were deliberately burned as part of campaigns to stamp out native religions. And time has taken a heavy toll on featherworks and textiles, which were considered more precious than gold by many indigenous societies. What we present in this show are not only spectacular artworks, but also rare and enormously important objects that escaped destruction.”

The exhibition present a new understanding

of ancient American art and culture, showcasing more than 300 objects

drawn from more than 50 museums in 12 countries

Exhibition Highlights

GOLD, SILVER and COPPER

In the ancient Americas, gold, silver, and copper were used primarily to create regalia and ritual objects—metals were only secondarily used to create weapons and tools. First exploited in the Andes around 2000 B.C., gold was closely associated with the supernatural realm, and over the course of several thousand years the practice of making prestige objects in gold for rulers and deities gradually moved northward, into Central America and Mexico.

But in many areas other materials were more highly valued. Jade, rather than gold, was most esteemed by the Olmecs and the Maya, while the Incas and the Aztecs prized feathers and tapestry. In all places, artists and their patrons selected materials that could provoke a strong response—perceptually, sensually, and

conceptually—and transport the wearer and beholder beyond the realm of the mundane.

PERU

Mouth Mask with Feline Creature and Human Figures

Mouth Mask with Feline Creature and Human Figures, Gold, Cupisnique-Chavín-800-550 B.C.

Peru-Kuntur Wasi_Tomb A-TM2, San Pablo_Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Image © Kuntur Wasi Museum.

Part of a group of funerary offerings for a male who died at about sixty years old, were found in a tomb under the principal platform at Kuntur Wasi. The mouth masks—a type of ornament worn suspended from the septum of the nose—feature feline creatures with prominent fangs; on one example the animal grasps human figures (seen in profile) in its claws. As there was no writing tradition in the ancient Andes, the precise meaning of this imagery remains unknown.

PERU

Octopus Frontlet

Octopus Frontlet, Gold, chrysocolla, shells, Moche A.D. 300-600, Peru, La Mina, Museo de la Nación, Lima,

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

This object would have been affixed to a cylindrical headdress. Made of gold sheet, it was cut into the shape of a supernatural figure with serrated octopus tentacles that terminate in catfish heads. The creature rests on two clawlike feet, depicted in low relief. Reportedly found at La Mina, in the Jequetepeque Valley, the frontlet is remarkably similar to an example illustrated on a ceramic vessel from Dos Cabezas.

PERU

Mosaic Earspools

Pair of Ear Ornaments with Winged Runners, Gold, turquoise, sodalite, shell,

Moche, A.D. 400–700, Peru, North Coast. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Gift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1966,1977.

Moche artists worked tiny pieces of highly valued materials such as shell, turquoise, and other blue-green stones into mosaics on the large circular frontals of ear ornaments. One pair here portrays winged runners, likely anthropomorphized owls, each holding a small bag. Darker inlays on the kneecaps, lower legs, and feet represent the figures’ body paint. Ritual running by a human or an anthropomorphized animal is one of the most frequently depicted activities in later Moche ceramics, but, as with the lizard motif on the other ornaments, its full meaning is unknown.

Ear Ornament Depicting a Warrior

Gold, turquoise, wood

Moche A.D. 640-680

Peru, Sipán,

Tomb of the Lord of Sipán

Sipán (Tomb 1)

Museo Tumbas Reales de Sipán

Lambayeque, Peru

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú

Photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Villanueva

PERU

Pair of Earflares with Multifigure Scenes

Pair of Earflares with Multifigure Scenes, Gold, Chimú, A.D. 1350–1470, Peru,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jan Mitchell and Sons Collection, Gift of Jan Mitchell, 1991

This pair of ear ornaments depicts a lord wearing a large crescent headdress. He is on a litter—the transport of choice for high-ranking Chimú individuals—held aloft by two figures wearing similar, smaller headdresses. The earflares are made entirely of hammered gold sheet, including the tiny hollow spheres around the disks.

PERU

Nose Ornament with Intertwined Serpents

Nose Ornament with Intertwined Serpents, Gold, silver; eyes restored,

Moche, A.D. 390–450, Peru, Loma Negra, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

Some of the earliest nose ornaments from Peru are attributed to the Salinar culture, which flourished on the North Coast, around present-day Trujillo. Successors of the Salinar, the Moche excelled in the production of gold-and-silver ornaments. Here, two intertwined serpents with canine characteristics are joined to the silver crescent with a series of tabs. Gold danglers, suspended by gold wire, would have moved with the wearer, catching the light and creating a sense of animation.

PERU

Nose Ornament

Nose Ornament,

Gold, silver, turquoise inlays,

Moche ca. A.D. 400,

Peru,El Brujo Huaca Cao Viejo,

Tomb of the Lady Cao, Museo Cao,

Magdalena de Cao, Peru,

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

Photo: Fundación Augusto N. Wiese

PERU

Pectoral

Pectoral, Gold, turquoise, and malachite or chrysocolla,

Moche, A.D. 200–600, Peru, North Coast, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru

PERU

Scepter

Scepter, Gold, Lambayeque, A.D. 900–1300, Peru, Chornancap, Tomb of the Priestess (Tomb 4)

Museo Arqueológico Nacional Brüning, Lambayeque, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Photo: Yutaka Yoshii

Found near the left hand of the Priestess of Chornancap, this scepter features a figure within a temple on top of its slender handle, a motif that goes back to Moche times, several hundred years earlier on Peru’s North Coast. The figure wears a shirt with a fringed border and a trapezoidal headdress with striations representing feathers. A U-shaped element with four zoomorphic heads surrounds the sides and bottom of the figure’s face.

PERU

Ceremonial Knift

Ceremonial Knift (Tumi), Gold, silver, turquoise, Lambayeque (Sicán), A.D. 900–1100, Peru,

North Coast, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1974, 1977

COLOMBIA

Pectoral

Pectoral, Gold Nahuange, A.D. 200–900, Colombia, Magdalena,

Santa Marta, Museo del Oro, Banco de la República, Bogotá.

A graceful union of two diverging spirals, this pectoral was made by artists in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the high mountain range on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. Although later Tairona artists are famed for their ornaments made using a lost-wax casting technique, this chest ornament—likely once affixed to a cotton garment—was fashioned from hammered gold sheet.

COLOMBIA

Pendante

Pendante, Gold, Tolima, 1B.C.-A.D. 700, Museo del Oro, Banco de la República,

Bogota. Photo: Clark M.Rodríguez

This pendant from Colombia’s Tolima region, around the Middle Magdalena River, depicts a figure with human and jaguar attributes. The object was cast using the lost-wax process, and its body and extremities were further shaped through hammering. While most of the piece was well polished, the face was left rough.

COLOMBIA

Bird-Man Pectoral

Bird-Man Pectoral, Gold, Cauca, A.D. 900–1600, Colombia, Museo del Oro,

Banco de la República, Bogotá. Photo: Clark M. Rodríguez

This chest ornament, one of the largest and most ornate cast-gold works known from the ancient Americas, depicts a man with avian attributes. Two small lizard-like creatures, shown in profile, perch on the figure’s wings. The wax model was carefully incised to show details such as the texture of the creatures’ skin and feet.

COLOMBIA

Nose Ornaments

Nose Ornament, Gold, Malagana, 100 B.C.–A.D. 300, Colombia, Cauca Valley, Palmira,

Museo del Oro, Banco de la República, Bogotá. Photo: Clark M. Rodríguez

Made of at least eighteen separate pieces of hammered gold, this nose ornament would have covered the wearer’s mouth and much of the face. The central image is itself a face, and its eyebrows, eyelids, lips, and beard, attached by gold wires, would have moved as the wearer moved. To either side are hammered gold sheet plaques with ten repoussé (raised relief) faces of stylized creatures in profile.

COLOMBIA

Lime Container in the Shape of a Jaguar

Lime Container in the Shape of a Jaguar, Gold, platinum, Calima-Yotoco, 100 B.C.–A.D. 800,

Colombia, Cauca Valley, López (Micay) Museo del Oro, Banco de la República, Bogotá,

Photo: Clark M. Rodríguez

This lime container (poporo) is made of many pieces of metal sheet crimped or joined by wire loops. The nose ornament was fabricated from platinum, a rare material that is difficult to work with. Unlike gold, silver, and copper, platinum is not easily hammered and has a high melting point. The thin spoon with a finial, inserted between the feline’s shoulder blades, would have been used to retrieve powdered lime.

PANAMA

Plaque

Plaque, Gold, Coclé, A.D. 700–900, Panama, Sitio Conte, Trench IV, Grave 32, Burial C,

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Photo: Michael Cardinali

© President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

MEXICO

Face Ornaments of Quetzalcoatl

Face Ornaments of Quetzalcoatl, Gold, Maya, A.D. 800–1100, Mexico, Yucatan, Chichen Itza, Sacred Cenote,

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Peabody Museum Expedition, 1907–1910,

Michael Cardinali. Photographer. © President and Fellows of Harvard College,

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

These eye and mouth ornaments together form a face mask that was likely used in rituals. Forked-tongue serpents with pointed, feathered plumes curve over each eye ring. Often called by its Nahuatl name, Quetzalcoatl, or its Yukatek name, Kukulkan, the feathered serpent was one of Chichen Itza’s principal deities and appears in many places on the city’s monumental architecture. Individuals wearing face ornaments like these are also depicted in artwork at Chichen Itza.

MEXICO

Serpent Labret with Articulated Tongue

Serpent Labret with Articulated Tongue, Gold, Aztec, A.D. 1300–1521. Mexico,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, 2015 Benefit Fund and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2016

Crafted in the shape of a serpent ready to strike, this labret (lip plug) was ingeniously cast as two separate pieces, so that the movable bifurcated tongue could be retracted or allowed to swing from side to side as the wearer moved. The curled eyebrow and snout and the feathered headdress may mark this creature as Xiuhcoatl, the mighty fire serpent and animate weapon of the Sun God, Huitzilopochtli. Labrets were insignia of military and political power, and specific types were awarded based on achievement on the battlefield.

MEXICO Shield Pendant with Darts

Shield Pendant with Darts, Gold, Mixtec (Ñudzavui), ca. A.D. 1500 Mexico,

Oaxaca (fabrication) Mexico, Veracruz (deposition) Museo Baluarte de Santiago, Secretaría de Cultura-INAH,

Veracruz. Image © Secretaría de Cultura-INAH. Photo: Michel Zabé / Art Resource, NY

MEXICO Necklace with Beads in the Shape of Jaguar’s Teeth

Necklace with Beads in the Shape of Jaguars’ Teeth, Gold,

Mixtec (Ñudzavui), a.d. 1200–1521, Mexico, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, Mariana and Ray Herrmann, Jill and Alan Rappaport, and Stephanie Bernheim Gifts, 2018.

MASKS

PERU

Funerary Object from Dos Cabezas

Burial Mask, Copper, gilded copper, shell, stone, Moche, A.D. 525–550, Peru, Dos Cabezas, Tomb 2,

Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Photo: Christopher B. Donnan

Funerary Object from Dos Cabezas. The young lord in Tomb 2 at Dos Cabezas was interred with several nose ornaments and this mask. He was likely wearing the rectangular gold nose ornament with a silver stepped-design border at the time of his burial. The X-shaped example featuring a monkey and Crested Animals had fallen down the left side of his face. The owl, with its projecting pale gold beak, was intentionally compressed at the sides and then placed in the young lord’s mouth. The bat ornament was found nearby.

MEXICO

Aztec Heirlooms and Emulations

Hornblende hornfels, Mask, Olmec style, Mexico, Guerrero, ca. 800 B.C. (fabrication) Mexico,

Tenochtitlan (Mexico City), Templo Mayor, Phase IVb, Offering 20, A.D. 1469–81

(deposition) Museo del Templo Mayor, Secretaría de Cultura-INAH, Mexico City Image

© Secretaría de Cultura-INAH / Jorge Pérez de Lara.

The greenstone mask featuring obsidian pupils appears to have been made in Tenochtitlan by Mexica artists emulating the ancient style of masks from Teotihuacan, a long-abandoned site near the Mexica capital. The Olmec-style mask was either passed down as an ancestral heirloom or excavated during Mexica times. These works signal the Mexica reverence for greenstone and for antiquities from illustrious civilizations of the past.

MEXICO

Mask of the Red Queen

Mask of the Red Queen, Jadeite, malachite, shell, obsidian, limestone,

Maya, A.D. 672, Mexico, Chiapas, Palenque, Temple XIII, Museo de Sitio de Palenque “Alberto Ruz L’Huillier,”

Secretaría de Cultura-INAH. Image © Secretaría de Cultura-INAH. Photo: Michel Zabé / Art Resource, NY.

Funerary Regalia of the Red Queen. The funeral assemblage of Palenque’s Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw, nicknamed the Red Queen because she was found covered in cinnabar, is one of the richest known burials of a female Maya ruler. Her sarcophagus was in Temple XIII, next to the Temple of the Inscriptions, where her husband, K’inich Janaab Pakal I, was entombed; her malachite funerary mask echoes his jadeite version. She also wore a headdress ornamented with shell eyes and fangs, probably representing a deity, and a collar of multicolored beads. A Spondylus shell containing a limestone figurine probably represents a dedicatory offering performed when the queen was laid to rest.

MEXICO

Mask

Mask, Turquoise, wood, mother-of-pearl, shell (Spondylus princeps, Spondylus calcifer)

Probably Mixtec (Ñudzavui), A.D. 1200–1521, Mexico, MiBACT Museo delle Civiltà –

Museo Nazionale, Preistorico Etnografico “L. Pigorini”. Image © Museo delle Civiltà –

Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico L. Pigorini, su concessione del MiBACT,

Photo Archive scans (Mario Mineo)

The face of this mask is framed by the jaws of a helmet in the shape of an animal’s head, with two intertwined xiuhcoatl (fire serpents). This type of turquoise was valued for its medicinal use and was worn or ingested by victims of lightning strikes. The quality of the crafting and the combination of turquoise with other materials likely indicates Mixtec manufacture. During the sixteenth century, this mask made its way to Europe and into the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Duke of Florence.

GUATEMALA

Belt Ornament with Head of an Ancestor

Belt Ornament with Head of an Ancestor, Jadeite,

Maya, Guatemala, Petén, Piedras Negras, A.D. 675–725 (fabrication) Mexico, Yucatan,

Chichen Itza, Sacred Cenote (deposition) Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,

Harvard University, Gift of C. P. Bowditch, 1910 © President and Fellows of Harvard College,

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

Kooj K’inich Yo’nal Ahk acceded to the throne at Piedras Negras (in what is now Guatemala) in a.d. 687 and ruled for more than forty years. This jade belt plaque, probably representing one of his ancestors, has two hieroglyphic inscriptions on the reverse commemorating his reign. The carving was so celebrated that the sculptor was allowed to sign it, creating perhaps the only known signature of a Precolumbian lapidary (jade worker). The ornament was deposited in the Sacred Cenote, some three hundred miles from Piedras Negras.

CERAMIC

PERU

Portrait Vessel

Portrait Vessel, Ceramic, pigment, Moche, A.D. 400–650, Peru, North Coast, Museo Larco,

Lima, Peru (ML018883) Photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra Villanueva.

The man depicted here, nicknamed Black Stripe for his face paint, is known from several portrait vessels. He has been identified as a warrior who was eventually taken captive. Here, he wears tubular ear ornaments and a cloth turban with lozenge-shaped danglers. Portrait vessels such as this example were used before they were placed in tombs, but there is no clear correlation with the buried individuals—portraits of men have been found in the tombs of females.

PERU

Vessel in the Shape of a Crested Animal

Vessel in the Shape of a Crested Animal, Ceramic, Moche, A.D. 525–550, Peru, Dos Cabezas, Tomb 2,

Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, Photo: Christopher B. Donnan.

PERU

Stirrup-Spout Bottle with Marine Shells

Stirrup-Spout Bottle with Marine Shells, Ceramic, Cupisnique, 1200–500 B.C. Peru, North Coast,

Museo de Arte de Lima, Ex Colección Óscar Rodríguez Razzetto,

Donación Colección Petrus y Verónica Fernandini.

PERU

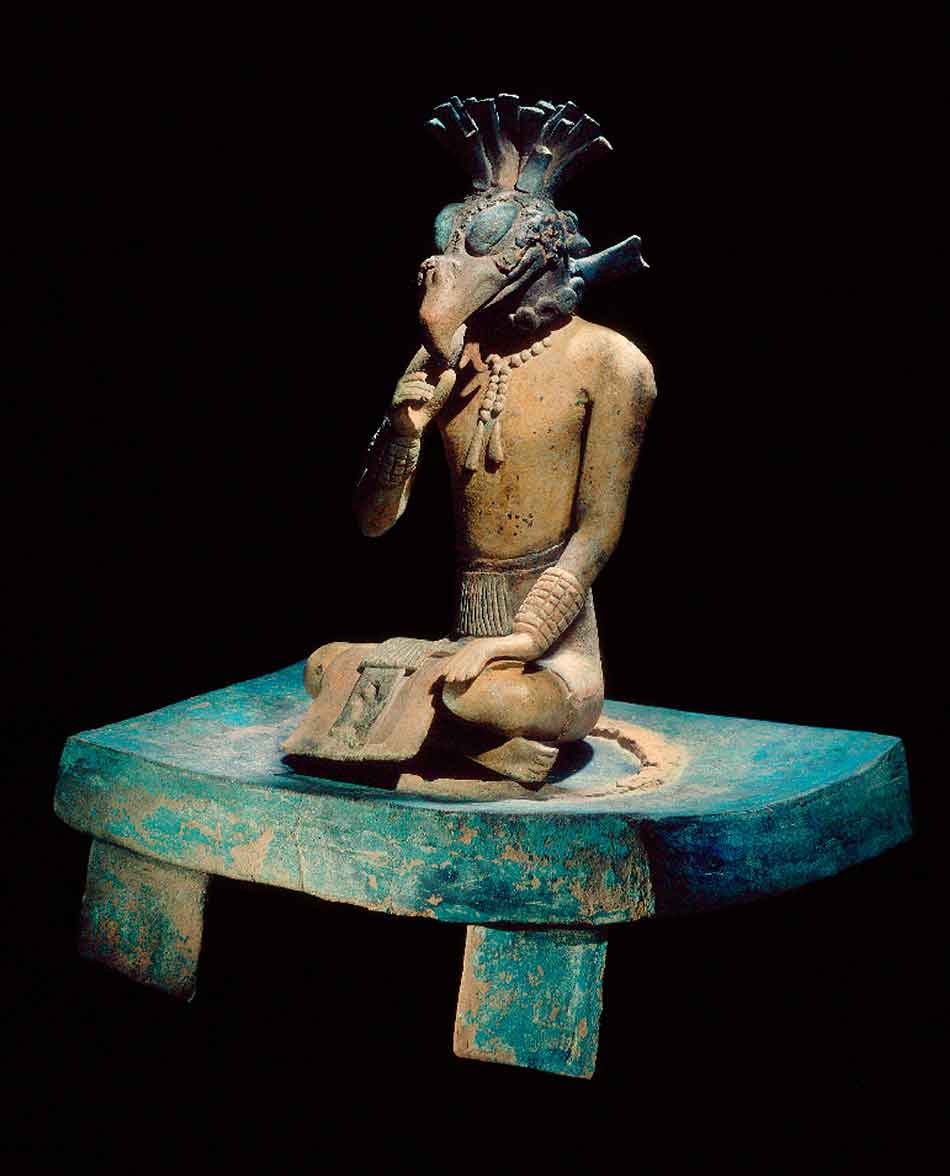

Figure with Bird Mask

Figure with Bird Mask, Ceramic, Maya, a.d. 550–900, Mexico, Chiapas, Palenque,

Building 3 of Group B, Tomb 1, Museo de Sitio de Palenque “Alberto Ruz L’Huillier,”

Secretaría de Cultura-INAH. Image © Secretaría de Cultura-INAH / Jorge Pérez de Lara.

As part of their royal duties, ancient Maya kings and queens would impersonate avian deities during masked performances. Found at the center of an altar in a tomb, this figurine portrays a ruler seated on a blue-green throne wearing a bird mask; the hooked beak recalls that of a raptor, and finely wrought details represent jade ornaments and luxury textiles.

PERU

Figurine in the Shape of a Dignitary

Figurine in the Shape of Dignitary, Wood, shell and stone inlay, silver,

Wari, A.D. 600–1000, Peru, South Coast, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

© Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

GARMENTS and TEXTILES

PERU

Checkerboard Tunic

Checkerboard Tunic, Camelid fiber, Inca, 16th century A.D. Peru,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Fletcher Fund,

Claudia Quentin Gift, and Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 2017.

An account of the first meeting between the Inca emperor Atahualpa and the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro describes Inca soldiers wearing checkerboard-patterned tunics. Such finely woven garments may have been bestowed on individuals in recognition of their valor. The Incas used textiles as political tools—given as gifts or demanded as tribute—in their relations with vassals as well as insurgent groups across their empire.

PERU

Pendant with Fishing Birds Spondylus

Pendant with Fishing Birds, Spondylus shell, turquoise inlay, Chimú, A.D. 900–1470. Peru, North Coast,

Pre-Columbian Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

© Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, DC

PERU

Mantle Camelid fiber

Mantle Camelid fiber, Paracas, 450–175 B.C. Peru, South Coast, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

William Alfred Paine Fund (31.501) © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A custom of burying prominent individuals with multiple finely woven, embroidered garments flourished on the coast south of Lima in the final centuries of the first millennium b.c. Hundreds of exquisitely patterned textiles—preserved underground in the arid desert—were recovered from cemeteries on the Paracas Peninsula. Among the many types of buried garments are mantles such as this one, which features colorful, animated figures with flowing hair and back-bent, human-shaped bodies dressed in tunics and skirts.

Detail of the design of Mantle Camelid fiber

PERU

Tabard with Lizard-Like Creatures

Tabard with Lizard-Like Creatures, Feathers on cotton, Nasca, A.D. 500–750, Peru, South Coast,

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund. Photo: Katherine Wetzel,

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

MEXICO

Collar

Collar, Shell (Spondylus princeps) Maya, a.d. 600–660, Mexico, Campeche, Calakmul, Structure XV, Tomb I,

Museo Arqueológico de Campeche, Fuerte de San Miguel, Secretaría de Cultura-INAH, Image

© Secretaría de Cultura-INAH / Jorge Pérez de Lara.

This shell collar, made of more than 380 Spondylus plaques, was among the offerings that accompanied the burial of a royal woman. She was placed on a wooden litter, wrapped in strips of fabric soaked in rubber to form a funerary bundle, and surrounded by offerings of sixteen ceramic vessels, several textiles, and honeycombs. Her body was adorned with ornaments made of jade, shell, bone, and flint. She may have been the wife of the ruler Yuknoom Ch’een II (r. a.d. 636–86), the self-proclaimed founder of the Snake-Head Dynasty at Calakmul.

MEXICO

Tabard and Necklace

Tabard and Necklace, Shell (Spondylus princeps, Chama echinata, Lyropecten subnodosus,

Oliva incrassata, Oliva spendidula, Oliva spicata, Oliva julieta, and Pinctada mazatlanica)

Toltec, A.D. 900–1200 Mexico, Hidalgo, Tula, Burned Palace, Room 2, Offering 2,

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Secretaría de Cultura-INAH, Mexico City.

This impressive tabard consists of 1,446 plaques and is accompanied by a 245-bead necklace. It may be a ceremonial cuirass (breastplate), as similar garments are depicted on warriors. Although shells are an eminently aquatic material, reddish ones, called tapachtli in Nahuatl—a language spoken in central Mexico—possibly symbolized fire. The piece may refer to atl-tlachinolli (meaning “water and fire”), a Nahuatl metaphoric couplet that signifies the union of opposing complementary forces in the cosmos and alludes to sacred war.

MEXICO

Clamshell-Shaped Pendant

Clamshell-Shaped Pendant, Jadeite, Olmec, 900–400 b.c. (fabrication) Mexico or Guatemala,

Costa Rica, San José Province, Talamanca de Tibás, Principal Tomb, a.d. 300–500 (deposition)

Colección Museo Nacional de Costa Rica/CCSS, San José.

These pendants were likely originally carved in the Gulf Coast region of what is now Mexico and then deposited at least seven hundred years later in a tomb with three stone metates at Talamanca de Tibás, a site near Costa Rica’s capital, some one thousand miles away. The clamshell-shaped pendant features a hand grasping a composite creature with the head and front arm of a felid, such as a jaguar or puma, and the segmented thorax and abdomen of an arthropod. The vertically oriented pendant was recarved into the shape of a bird, a style distinct to Costa Rica.

STONES

MEXICO

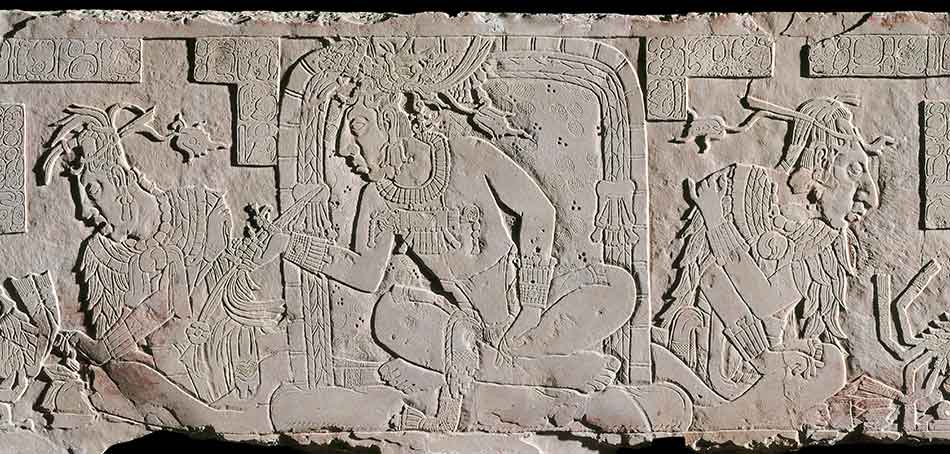

Platform Panel of Temple XXI

Platform Panel of Temple XXI, Stone, pigment, Maya, A.D. 736, Mexico, Chiapas, Palenque,

Temple XXI, Museo de Sitio de Palenque “Alberto Ruz L’Huillier,” Secretaría de Cultura-INAH. Image

© Secretaría de Cultura-INAH / Jorge Pérez de Lara.

This panel carved in low relief was originally the front of a platform. The Maya ruler K’inich Janaab Pakal I, depicted posthumously at the center of the composition, impersonates Palenque’s mythological dynastic founders. Enthroned on a jaguar-pelt backrest, he hands a stingray-spine bloodletter to K’inich Ahkal Mo’ Naab III, his grandson and the patron of the panel. K’inich Janaab Pakal II, brother of Ahkal Mo’ Naab, is to the right of Pakal. The panel records the first bloodletting ceremony, a rite of passage, performed by Ahkal Mo’ Naab, which may have taken place in the late 670s or early 680s, when he was a child. image caption: drawing courtesy Constantino Armendariz Ballesteros.

Detail of Panel of Temple XXI

MEXICO

Winged Pectoral with Maya Hieroglyphic Text

Winged Pectoral with Maya Hieroglyphic Text, Quartzite or serpentinite,

Olmec, 900–400 B.C. (initial fabrication) Maya, 100 B.C.–A.D. 100 (incised reverse) Mexico,

Southern Lowlands, Pre-Columbian Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

© Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, DC.

Created in Guerrero or Oaxaca, this pectoral represents the face of the Olmec Maize God. Hundreds of years later, probably in the first century a.d., a Maya ruler commissioned an artist to incise an image of him wearing regalia on the back of this revered heirloom. The accompanying text probably names the ruler and describes his accession. To emphasize his belief in the divine nature of his rulership, the Maya patron likely wore the pectoral with other jade regalia while impersonating the Maize God.

MEXICO o GUATEMALA

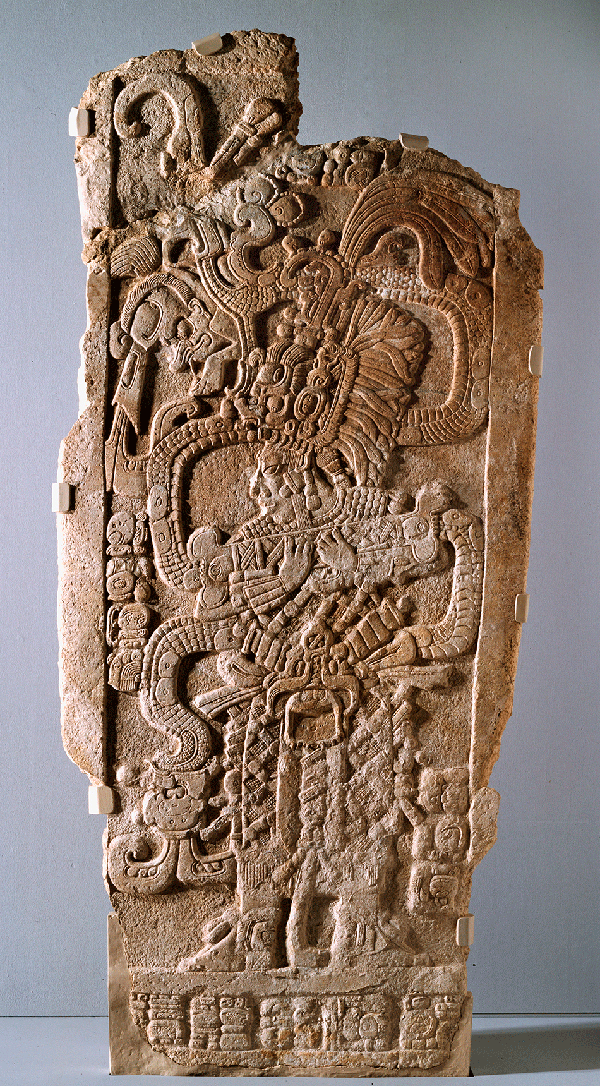

Stela with Queen Ix Mutal Ahaw

Stela with Queen Ix Mutal Ahaw

Limestone

Maya, A.D. 761

Mexico or Guatemala

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

Gift of Mrs. Paul L. Wattis

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco

Maya dynasts often revered their wives and mothers as vital players in their claims to the throne by featuring them as important subjects for commissioned artworks.

This stela, from an unknown site in the Usumacinta River region, is a masterful depiction of such a royal woman.

The inscription refers to her as Ix Mutal Ahaw, or “royal lady of Mutal.”

Mutal refers to the powerful dynasty at the city of Tikal, Guatemala, or a related lineage at the site of Dos Pilas.

She holds a ceremonial bar from which a supernatural serpent emerges.

A version of the Maya God of Lightning, K’awiil, appears from the serpent’s mouth.

This image of a queen in her regalia of resplendent quetzal feathers and jade ornaments underscores the central role of women in conjuring deities.

GUATEMALA

Celt Cache

Celt Cache, Jadeite, Maya, 800–600 B.C. Guatemala, Petén, Cival,

Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City. Photo © Jorge Pérez de Lara.

In 2003, archaeologists uncovered a spectacular cache in the center of a plaza at Cival, a site in northeastern Guatemala. These five blue-green jade celts were set upright in the middle of a cruciform pit cut into the bedrock, their quincunx arrangement marking the four directions and the center. More than one hundred jadeite pebbles were found below the celts, and five large water jars were placed on top of the celts. Symbolizing agricultural fertility, the offering was then covered and a large post representing the World Tree—the cosmological center of Maya communities—was raised.

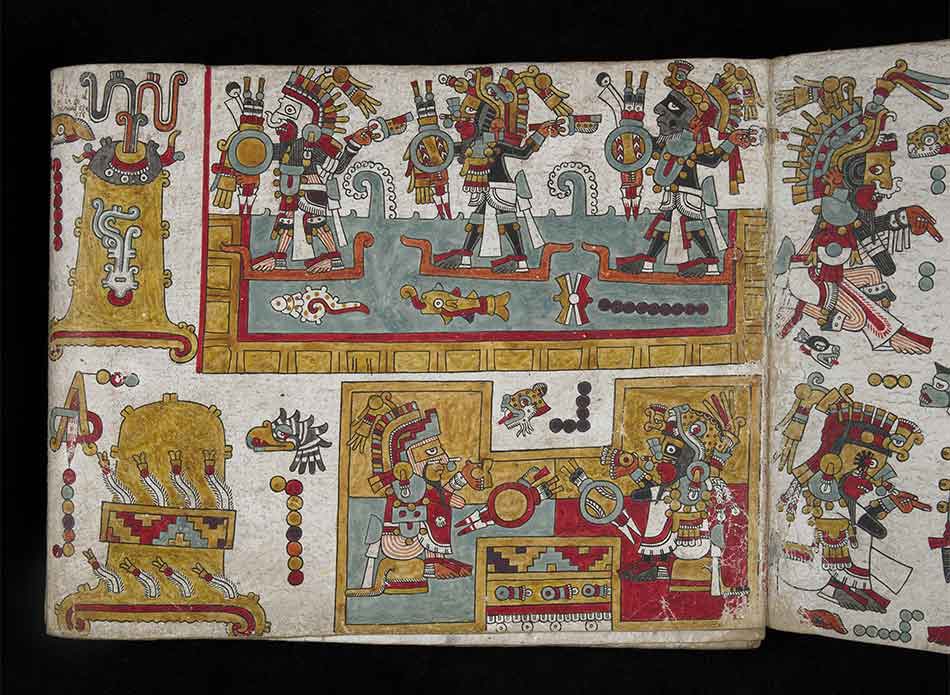

CODEX ZOUCHE-NUTTALL

Pages 86 (left) and 85 (right)

Codex Zouche-Nuttall, Pages 86 (left) and 85, (right) Deerskin, gesso, pigment,

Mixtec (Ñudzavui), A.D. 1350 (reverse), A.D. 1450 (obverse) Mexico, western Oaxaca, British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY.

Painted on both sides, at different times and by different artists, this screenfold manuscript is made of sixteen strips of deerskin that were glued together and painted with brilliant colors, including red cochineal, Maya blue (indigo and palygorskite, a type of clay), and yellow orpiment. Read from right to left, it traces the genealogy of Mixtec nobility to the tenth century. The codex depicts Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw receiving a gift from the Sun God, accompanied by Lord Four Jaguar, all identified by name glyphs. Luxuriously dressed, they sit on jaguar-pelt thrones, perform rituals atop temples, journey over water in canoes, and interact in an I-shaped ballcourt.

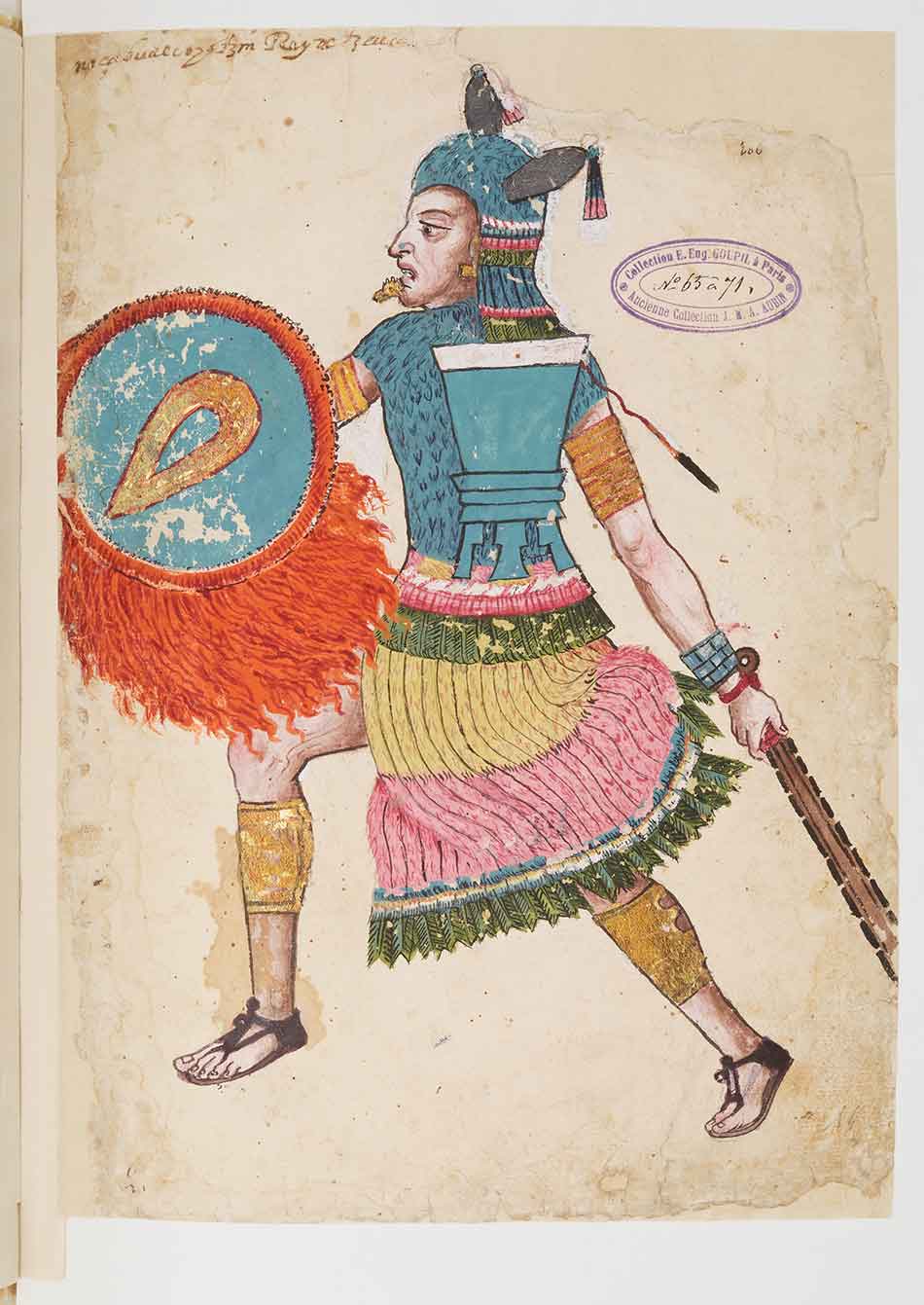

CODEX IXTLILXOCHITL

Folios 105 (verso) and 106 (recto)

Codex Ixtlilxochitl, Folio 106 (recto) Paper, pigment,

Nahua-Spanish, A.D. 1582, Mexico, Tetzcoco,

Compilation attributed to Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (Nahua-Spanish, ca. A.D. 1578–1650)

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

These folios depict the Tetzcocan ruler Nezahualcoyotl (Fasting Coyote, 1402–1472) as an armed warrior charging into battle. Tetzcoco was one of the three central Mexican city-states that made up the Triple Alliance, the political union at the heart of the Aztec Empire. Clutching his macuahuitl, an obsidian-edged weapon, the ruler carries a huehuetl drum on his back and wears gold arm and leg bands, a gold eagle lip plug, a feather garment, and a large round feather shield. The painter utilized European modeling and proportion as well as gold leaf, but the costume testifies to the artist’s knowledge of traditional indigenous royal and military attire.

FOR NEW GODS AND KINGS

Spanish Viceroyalties, Sixteenth Century

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish Conquest brought destruction to the indigenous cultures of the Americas. Local rulers were assassinated, temples were razed, and populations were devastated by diseases introduced by Europeans. Once Spanish rule was established, the wealth of the Aztec and Inca Empires and a multitude of other kingdoms was appropriated and diverted to Europe, particularly to Spain. Christian clerics soon arrived in the Americas, with the fervent mission to spread God’s word and extinguish native religions.

Indigenous peoples, especially in Mexico, were perplexed by the Spanish obsession with gold, as they considered jade, turquoise, shells, feathers, and textiles to be far more valuable. In contrast, the Spaniards happily traded green glass beads for gold objects, which they melted down for easy storage and shipment. Despite this cultural rupture, indigenous artists adapted to the new colonial context and continued to practice traditional arts. This melding of customs and beliefs was especially evident in missionary schools, where native artists created Christian images and artworks in media such as feather mosaic. The Americas quickly became the center of a global mercantile crossroads, in which exotic goods and artistic knowledge from Europe and Asia circulated and blended with ancient indigenous traditions.

Andrés Sánchez Galque

Andrés Sánchez Galque (Andean, active Quito, about 1599)

Don Francisco de Arobe and Sons Pedro and Domingo, A.D. 1599, Oil on canvas,

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (PO4778) © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Francisco de Arobe is shown here with his sons, Pedro and Domingo, during an official visit to Quito in 1598. Francisco—a political leader from the Esmeraldas coast (Ecuador) and the son of an escaped African slave and an indigenous Nicaraguan woman—swore allegiance to the Spanish king in exchange for the governorship of an extensive region dominated by African descendants and the allied indigenous population. The sitters wear a combination of Spanish attire—ruff collars, silk doublets, and wide-brimmed hats—and traditional Andean textiles, shell necklaces, and gold nose and ear ornaments to create a striking portrait of power and luxury in a newly globalized world.

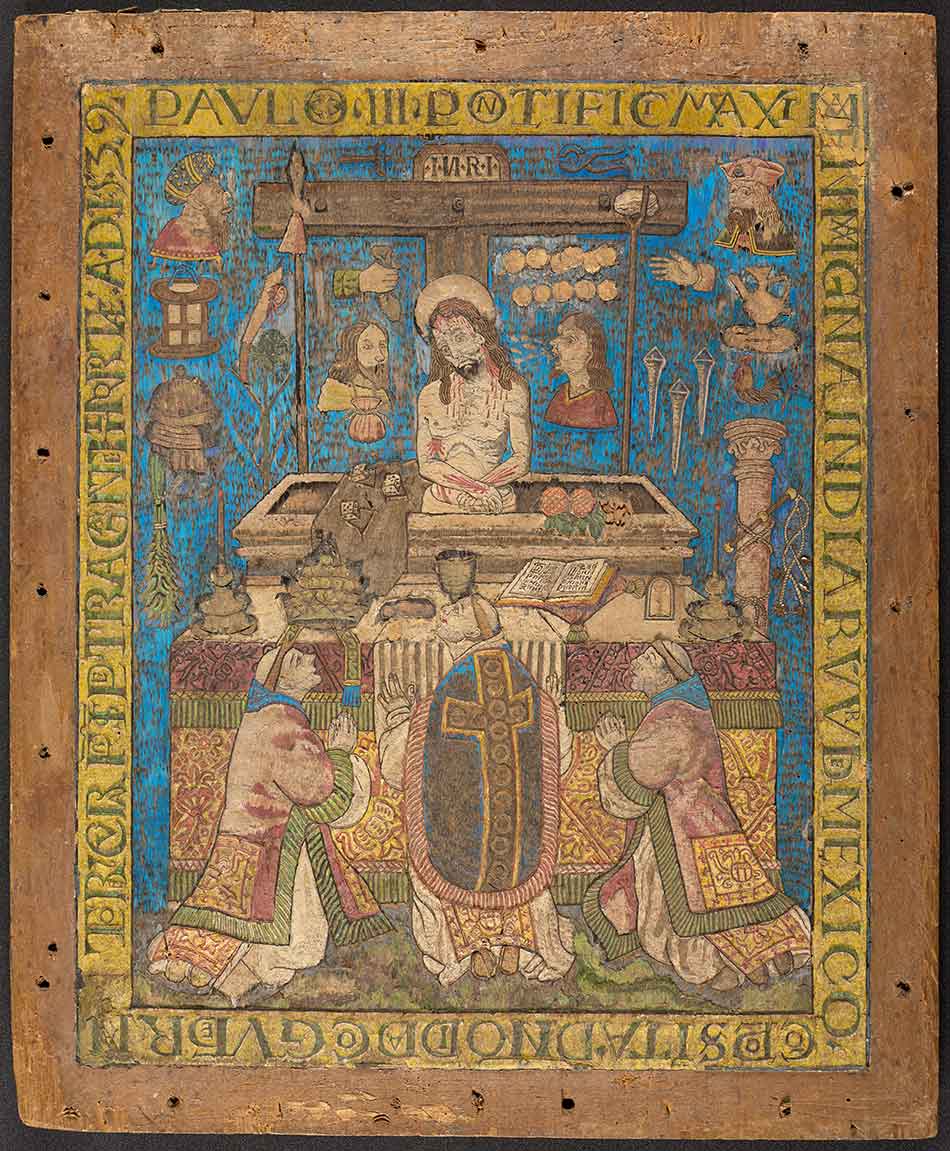

Mass of Saint Gregory

Mass of Saint Gregory, Feathers, gold, wood, pigment, Nahua, A.D. 1539,

Mexico, Mexico City, Musée des Jacobins, Auch (986.1.1)

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Based on a European print, this colonial feather mosaic represents the melding of indigenous and European artistic traditions. Combining colorful iridescent feathers with gold sheet, it depicts the sixth-century pope Gregory consecrating the Eucharist. Christ’s body miraculously appears behind the altar, proving to the doubting congregation the miracle of transubstantiation, the belief that the sanctified Host turns into Christ’s flesh. The inscription details that Friar Pedro de Gante and Don Diego Huanitzin, Mexico City’s governor, commissioned the work as a gift to Pope Paul III, whose 1537 papal decree defended the rights of indigenous people.

THE CURATOR’S VOICE

The Catalogue

The Catalogue

Golden Kingdoms:

Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas

Editors: Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter

Publisher: J. Paul Getty Museum

Pages: 328

Illustrations: 428 in full color and 4 maps

Dimensions: 9 5/8” x 11 3/4”

Format: Hardcover

ISBN: 9781606065488

Price: $59.95

Edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter.

This volume accompanies a major international loan exhibition featuring more than three 300 works of art, many rarely or never before seen in the United States. It traces the development of gold working and other luxury arts in the Americas from antiquity until the arrival of Europeans in the early 16th century. Presenting spectacular works from recent excavations in Peru, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Mexico, this exhibition focuses on specific places and times— crucibles of innovation— where artistic exchange, rivalry, and creativity led to the production of some of the greatest works of art known from the ancient Americas. The book and exhibition explore not only artistic practices but also the historical, cultural, social, and political conditions in which luxury arts were produced and circulated, alongside their religious meanings and ritual functions.

Daniel H. Weiss,

President and CEO of The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

“It is a great privilege for The Met to present this stunning assemblage of highly prized works of art from more than 50 organizations. This exhibition is the result of an intensive five-year research effort that brought together scholars from across Latin America and the United States, and we’re thrilled to share their findings and these beautiful objects with our visitors.”

CURATORS Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas is curated by The Met’s Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of the Ancient Americas, in collaboration with Timothy Potts, Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum; and Kim Richter, Senior Research Specialist at the Getty Research Institute.

SPONSORS

The exhibition is made possible in part by

The exhibition is made possible in part by

DAVID YURMAN

“Early in my career as a sculptor, I was captivated by the antique torques at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. At the beginning of our relationship, my wife Sybil and I would frequently visit the Museum for creative inspiration. My fascination with ancient jewelry became the catalyst to make historical forms contemporary. We are proud to sponsor Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas.”

ADDITIONAL SUPPORT IS PROVIDED BY

the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, Alice Cary Brown and W.L. Lyons Brown, the Estate of Brooke Astor, the Lacovara Family Endowment Fund, William R. Rhodes, and The Daniel and Estrellita Brodsky Foundation.

THIS EXHIBITION IS CO-ORGANIZED BY

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Getty Research Institute.

SEE ALSO ABOUT JEWELS

BOSTON MADE, Arts and Crafts Jewelry and Metalwork, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

EAST MEETS WEST, Jewels of the Maharajas from The Al Thani Collection, Legion de Honor Museum

MAGNIFICENT GEMS, Medieval Treasure Bindings, The Morgan Library & Museum

READ MY PINS, The Madeleine Albright Collection, Legion de Honor Museum

JOAQUIM CAPDEVILA, Book

VER TAMBIÉN SOBRE JOYAS

EL CUERPO TRANSFORMADO, Metropolitan Museum of Art

GOLDEN KINGDOMS, Lujo y legado en las antiguas Américas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

JOYAS DE LOS MAHARAJAS, Museo Legion de Honor

EL LIBRO JOYA, Lujo en la Edad Media, The Morgan Library & Museum

LEE MIS BROCHES, Colección de Madeleine Albright, Museo Legion de Honor

JOYA TIBETANA Y DEL HIMALAYA, Colección privada

JOAQUIM CAPDEVILA, Libro en idioma catalán

THE MET

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028

Phone: 212-535-7710

https://www.metmuseum.org/